Join Curator Exhibitions Penny Grist to hear about Hoda’s recent book and upcoming exhibition Speak the Wind, and to chat about portraiture, photography, and her life as an artist over the last few years.

Artist Hoda Afshar won the National Photographic Portrait Prize in 2015, and was a judge of the Prize in 2019. Her work has been exhibited Australia-wide and globally, and she was recently awarded a Sidney Myer Creative Fellowship.

- Hello, everyone, and welcome to another "In Conversation" with the National Portrait Gallery. We're so excited to have you all coming in today into our Zoom room for what I'm sure will be a very interesting conversation between our curator, Penny Grist and Hoda Afshar, who is a dear friend of the National Portrait Gallery, former winner of the National Photographic Portrait Prize, and also a judge of that Photographic Portrait Prize, but today we're gonna hear about her photography, and I can't wait to share that all with you. Before we get underway, I'd like to acknowledge that I'm broadcasting today from the beautiful lands of the Ngambri and Ngunnawal peoples here in Canberra, as are most of my colleagues. However, we are distributed around Canberra. We're not actually at the gallery today. We're still in a little bit of hybrid working arrangements so I am in my bedroom, and I think Penny is in her living room, but we are, for all intents and purposes, coming to you from the National Portrait Gallery. We're super interested to see where you are all coming to us from. If you'd like to let us know the lands on which your zooming in from, that would be great. Please pop it into the chat, in the Zoom chat at the bottom of your browser. That's also a really great way to interact with us throughout the programme. If you'd like to pop any questions or comments in there, I'll try and share as many of those as I can without presenters, today. So without any further ado, I'd like to hand over to Penny who'll introduce Hoda to us.

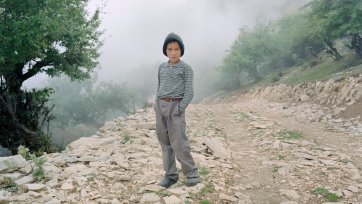

- Thank you so much, Gill. Now this is a huge treat for me to begin this year, talking with one of the Portrait Gallery's old friends, Hoda Afshar. It's been a huge pleasure for me to catch up with Hoda, preparing this programme and today, and to share her beautiful work. So Hoda's coming to you from Naarm, Melbourne, on the lands of the Bunurong Boon Wurrung and Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung peoples of the Eastern Kulin Nation, and as Gill said, I'm here in the Ngunnawal, Ngambri lands here in Canberra or Canberra. So I thought we should begin this talk, Hoda, and begin the story in four places, so we're gonna start in Northern Iran in 2014, in the Portrait Gallery in 2015, and also in London and Melbourne in 2020 and 2021, and now all these places are going to lead back to your book and forthcoming exhibitions, "Speak the Wind" that we are gonna focus on talking about today. But just to lead us in there, Hoda, can you bring up Hoda's 2015 National Photographic Portrait Prize-winning work, "Portrait of Ali." Now, Hoda, I wasn't involved in judging or curating this prize, but I did travel doing the curatorial talks with this work when that exhibition travelled around Australia, and it's an extraordinary piece of work, and I would love to hear your reflections as an artist, looking back at both this portrait as well as the experience of that time in 2015.

- Thank you so much, Penny, thanks for inviting me to be on the programme today, and it's always a pleasure connecting again to National Portrait Gallery. I think I mentioned it a few times to you that how special it is, that place, that museum to me and the events of that year and winning the National Portrait Prize in 2015 played a huge role in my career and it was at that point that, you know, like being a migrant in Australia and being really passionate about what you do but then also not knowing whether you would have a place or your voice would be recognised in those institutions at any point, it was like a booster to my career and it gave so much confidence to me and motivation to continue doing what I do, and I'm always very grateful for that. The portrait that I made of Ali was part of a bigger project that is still ongoing, called "In the Exodus, I Love You More." It's about my relationship to Iran as a migrant, and I continue making work for the series every time I return because I return quite regularly, my whole family lives there, and I started making it as, like it was very personal to kind of, like when I'm in Iran, I'm a very different photographer, I carry a camera, I have the urge to make pictures of things. It's the desire to record moment which is very different here. When I make pictures here, I start with an idea and I construct it, so I make the pictures here but I take pictures over there. So it was like part of the same process of making that series and keep adding more pictures as I travel around Iran, and, yeah, it was one of those really magical moments that most photographers experience in their career like I was walking around that landscape in north of Iran which is really foggy, and I was staying in a village that was above the clouds, basically, it was hours of travelling through and getting to that point and I was making pictures of horses and trees and then at some point I turned around, I saw him standing or appearing through the fog in that landscape, and I kept asking him if I can take his picture, but he just only offered me little berries in return, and he was very curiously looking at my big, medium-format camera. So when I was taking the picture, because it's analogue film, I couldn't see what I took, but in that moment, I knew that I captured something really special, and when it was, when I submitted it for the Portrait Prize, I didn't really think that people would respond to it in that way, and when it won the prize, it was, yeah, like a dream coming true for sure.

- Hoda, it's so lovely to hear because that's not quite, it's almost like eight, nine years ago now, and it's always lovely to hear an artist reflect back on work that's been really important and for the eagle-eyed people in the audience, you can actually see "Portrait of Ali" there, the bottom of the work there behind Hoda.

- Yeah, it's still here in this room.

- So, let's go to the next set of two places that we're starting this story, so London and Melbourne. Hoda, this is sort of just a general question about your experience in the last two years as an artist. Tell us about your journey and your not journeys in the last two years.

- You mean in terms of the pandemic and the lockdown?

- Yeah.

- I think I can claim to be the most lockdown person in the world. I don't think there are people that can compete with me on that because I did go through the first long lockdown of Melbourne in 2020 when it started, and then I had a residency with the Australian Council for six months to go to London in September to work on the publication of my first book with MACK Publishing, which was a very exciting event for me, and I didn't wanna miss out on it, and Australia's lockdown seemed to be never ending and everyone was really going through a tough time here, especially in Melbourne, and I thought I should go, and then I arrived in London and after a couple of weeks, Melbourne opened, the lockdowns ended there and the Delta variant started in London which meant that for the entire six, seven months that I was there, it was basically trapped in an apartment, I couldn't leave, and the situation was pretty horrific there. It was 1,000 death a day and 50,000 new cases, and no one would let anybody from the UK and I couldn't come back to Australia, I couldn't go to Iran, nowhere. It was just basically all the borders were shut to the UK people. So I was left there, alone in that apartment with all these images that I had to work with, and in some ways during the lockdowns, I started thinking about how lucky we are as artists, because we're trained to work in that way when you're working on a project, you do have to go into a mental lockdown when you're trying to get it to that point of fruitation or just realisation and so on. So I used that opportunity, as difficult as it was and mentally really draining, but I tried to use it positively and just work obsessively on that project and at the same time, I was presenting a big commissioned work as part of the Photo 2021 festival in Melbourne, which was being displayed, I had to complete it also when I was over there, so I worked like a maniac, basically 24/7, to ignore what was happening and just to also making a book with a publisher like MACK, really requires that level of sensitivity and attention to detail. So I use it as an opportunity to do that and drowned myself with images basically. But then when I returned to Australia, I had to do two weeks of quarantine in Adelaide, and then two, basically, a month after I arrived, then the next lockdown, series of lockdowns have started so I think all together, I did 15, 16 months of lockdowning, which was crazy, but I hope that I'm still sane. You tell me if I sound sane.

- I have to say, I mean, it's actually really, it's really inspiring and lovely to hear such an optimistic and positive reflection on going through that experience and that experience as an artist and what you were able to create during that time and I suppose the journeys that you were able to take in your mind and imagination back through your work even though you were physically constrained in that way, and now, and because of that work, you're able to share that with us through your book, and this book is also about to become an exhibition at Monash Gallery of Art this year too. So let's talk about "Speak the Wind" and maybe draw that connection for us between "Portrait of Ali" and this particular project, and how it came about, and the title "Speak the Wind" as well. I'm gonna hand over to you to introduce us to this incredible project, Hoda.

- Thank you so much. I think for those people who know a bit about my work, they know that it kind of, the visual language is quite diverse, what I use. It's mostly connected through the themes that I'm interested in which deals with questions related to visibility, representation, marginality, and so on, but then, I often allow the subject to determine the aesthetic of what I make instead of using the same aesthetic applied to other things. But in the context of the "Portrait of Ali," as part of the series that I was making in Iran, this project, the "Speak the Wind" also grew out of that project because again, it was part of the process of me travelling in Iran and for the first time, I arrived in south of Iran and then I was, again making pictures, thinking that would be part of the, in the "Exodus" series, but I became quite obsessed with the place, and the experience that I had there was beyond magic or anything that I could even dream of. I found myself in a landscape that I never encountered before, and the connection between the people and the landscape and how one determines the other, as an image maker, was an absolutely fascinating landscape to me. But then I was obsessively returning and wanting to know more about the history of the place, and the more I returned, the more I learned about it and also through my research, I found out about the history of a slave trade in the Persian Gulf region and how the entire island is believed that that place is possessed by wind that comes from East Africa. I was curious to know why East Africa which led me into learning about the history of slave trade, centuries of a slave trade, basically, 13 centuries, and it only ended in 1927, but like the majority of the people of African descent drifted towards south of Iran because they could mix with the people down there due to darker skin colour but still they're subject to severe racism in the region, and the only time that the dynamic changes, the power dynamic changes is when people who are possess need to have, need to see shamans of African descent to negotiate peace with the possessing wind in their bodies so that, to me, was something that really kind of started this project. I realised that this needs to be a separate project from what I was doing before, but it is still, I uses the same visual language, in some ways, documentary language but as you know, I'm very much interested in portraiture. A lot of my works includes, like one aspect of it is always portraits and then drawing the lines between identities, history, and also how to image invisible entities like history and wind and the spirit possession and in my case, my own experience of the real magic which was through the landscape. So all these entities were kind of like related to very similar themes that my practise is engaged with, and I wanted to bring them into the work. Are you sharing my slideshow here now? Okay. Thanks. There's, okay. There's a video of the book, shared by MACK Publishing on YouTube, which you can find it there, and I'm showing bits and pieces of it here like making the book was a very long process because I made these pictures of a five years of travelling back to the islands over and over again, and then when MACK approached me with the idea of publishing it as a book, like thinking where to start and where to end and how to go about making the book was something that took a long time to process. So like at some point, I realised that the book needs to go into smaller chapters, that each chapter deals with one aspect of the story because it's a very complex multilayer history, and for me, the idea of looking at the history of ethnography and ethnographic photography and how it addresses these issues and how I want it to challenge that by refusing to have a linear or definitive kind of narrative that is rationalising what's going on there and so on so I refuse to have a linear narrative in there. The book starts with the images on the cover and it's like going on a loop and ends with the other image at the back because those images don't exist inside the book and there's no gap. You open the book and you see the first image and there's like the gate fold that the text inside of it, I ask the Australian writer and anthropologist, Michael Taussig to write a text for the book which is, his writing really inspired me for this project. He approaches ethnography the way that contemporary photography approaches documentary like what's true and what's not, what's real and what is fiction. You see the beginning and end is the same mountain, one from, one's at the back and the other is from the front in black and white and colour, and photographing the mountains for me, was a way of photographing the wind because the mountains look like the statues, and the locals believe that the statues, the mountains are carved over millennia, by the wind. This is the first moment that I arrived, like the first time I arrived in the islands, and one of the locals painted my face with the glowing red sand of the island and behind me is the Persian Gulf and the blue waters that, I remember, it was right after watching a group of dolphins in the silence of the morning, jumping out of the water, I was blown away, and this is the moment that I kind of was, maybe possessed by the spirit of the island. That's what the locals always tell me that you are possessed, that's why you keep returning. But there were two different elements to the place that drew me, basically, one was this absolutely, surreal, magical look of the landscape which to me was like walking through a Pixar animation, basically, and then it was also then the connection between people and the landscape, how the landscape inspired the costumes and the clothing. And then the narrative that I spoke to you about about the possessing wind was like when I, like in different islands that I travelled, people wear different masks, and I was told that the wind possesses women, mostly, and it harms women more than men, although there are lots of men who are possessed too, and some of the locals told me that the masks they wear is like, as you can see, it looks like a thick moustache and eyebrow which makes women, it's to protect them from the possessing wind in some ways, which to me was also a very fascinating aspect of the story. I went to a lot of the rituals and ceremonies of a spirit possession to learn more and more about how it operates. This is a family who basically performed, I made a film also in there, it's a two-channel video installation in collaboration with this family which I took the camera to them and I told them that, like treat the camera as a possessed patient and we put a fabric on the camera, and the performance was basically dismantled intersections performed for the camera, basically there. Some of the, these are some of the researchers that I did which I have to skip, but this is Michael Taussig's writing that really inspired me, especially "I Swear I Saw This" book, which is his field note drawings that he did in Southern America, and he wrote this book about how he tried to instead of taking pictures, he used drawings to capture the magic of the place, things that he felt he can't even express through words or images, and the magic of the drawing, how you can actually encompass that experience and so on. That's why I found it so relevant to the project. This is my residency in London. This is the life that I was telling you about for months and months. I had all these prints laid on the floors, and I was running out of wall spaces, but I needed to spend that time with it to find these kind of dialogues between the images, but the most difficult part was where to start, and that's why I decided to put them in small groupings, really simple groupings of what the material I have, what am I dealing with, animals, black and white landscape, figure, drawing, and so on, and from there, finding these conversations between the images that could reflect what I was trying to narrate about the beauty of the place and the relationship between the identities of the people and the landscape, and as you can see, photographically, I'm trying to really bring that into the work through these pairings. But again, by choosing black and white as a separate section was a decision that I make to kind of move between these spaces that is between the oral history of this possessing spirit in the island that is represented through the black and white sections where these are images of the locations where the possessing wind exists, and then moving throughout the book, you constantly move from the reality that is reflected through the colour images and back into the black and white spaces. So the process was, first, finding these pairings and then from there, I was sending them to Michael Mac and the designer, and we were having meetings on how to go about constructing the book, and then after finding the pairings, we started laying it out again into the PDF and then work on the design and then again, print them out, lay them on the floor to find the right flow for the book. So if you, you will see in the book that there are these different sections, again, from colour to black and white, but then the black and white sections include also, as you saw in the film, there's French fold because I asked the locals to make drawings of the possessing wind because the majority believe that they've seen it before. So how to bring that into the book was to place them inside the black and white landscape and also the text, both in Farsi and English, is taken from the interviews I did with the possessed people that they talk about the physical experience of being possessed. As you may know, I'm very much inspired by cinema and slow cinema. Often in my work, I try to bring that element into the work as well through the montage and staging and so on. And this is the dance that a possessed person do when they being in the ritual and the drums are playing, so we did perform that in the landscape, and by the repetition, there's a section in the book, you see the dance that is interrupted with these cuts, because the image is wrapped around the pages, you move from one page to another. These two are, again, the cover images of the book, the front and the back, which what we wanted to do was to capture that magic and the dream, something that encourages people to pick up the book, something ambiguous but also reflective of the story. Anyway, I think I should end it here and let you respond or ask questions.

- Yeah, thank you so much, Hoda. I mean, there's so much to talk about there, and something that really strikes me is that, it's so generous of you to share your process with us, because when you've got such a beautifully composed book that feels right and every part of it looks together conceptually and visually and aesthetically and in terms of the stories that you're exploring, it looks like such a complete finished piece, and it's actually quite hard to imagine it not being that whole, and to see how you worked through, you know, just that glimpse of your very residency in London, is just so, I think it should be so inspiring for photographers out there to know that there's that working through that process in the making of a book like that is, and you end up with this beautiful presentation that's this beautiful object at the end as well as a contained story. So, just tell, just expand a little bit on that, I suppose the dynamics of a book and curating those in that like you talked about the pairings, but also the, yeah, that structure of a book and how you grappled with, particularly the place of portraiture within the book is being inseparable from the other elements.

- For sure. I think, thank you, firstly, for saying that because making a book has like, was a very emotional process for me. There's so many moments of doubt that luckily I had friends who I could actually, friends that I trust their vision and knowledge of the area that I could actually share it with and send it back and forth, and it's a very different medium. Working with book, to me, it's a lot closer to filmmaking and montage than working on an exhibition, which is something that I'm more accustomed to than making a book, and translating a project into a book requires a very different way of thinking about a series of images and how to make it flow and interesting enough and so it was a very long process but then also the role of the portraiture in the project is something that I was intentionally playing with. The beginning and end section are, there are two different chapters of colour, colour images, one is the beginning and one is towards the end that, like the faces are refusing to look into the camera or just like the portraiture is basically fit portraits without faces. It's like playing with this idea of who's looking at who, and the gaze of the subject that is refusing to look or sometimes also trying to look at the body as part of a bigger landscape, that body and the landscape merged together. So in the first two colour sections, you don't see any faces, but then, and then it's like playing between those two chapters and the black and white sections that, again, the face is absent there but present, the body is present, but then it's only in the middle of the book that you see all these faces with and without the mask, staring at the audience and looking into the camera directly, which is the traditional idea of a portraiture. So for me, it was a lot present in the work and the process thinking about what is a portraiture like how do we approach the idea of the face in our portrait and so on so I don't know if that answered your question, did I?

- Yeah, absolutely, absolutely, and I think Gill has a question from our audience.

- Oh, thanks, Penny. Our friend Nita was just wondering, Hoda, how you negotiate that immovable object that is the break between pages and how you approached that aspect when it comes to a visual book having to have that fold right down the middle and there's just no way you can get around it?

- Um, you mean like how I negotiated that with the publisher?

- Oh no, sorry, just where, how you negotiate where the cut falls when you are placing in images together and, you know that kind of notion of having it to have like a fold appear across images, et cetera?

- Ah, yes, yes. That's something that, again, like it was something in the process with the designer and Michael Mack that we discussed a lot that allowing the photo book format to also be present at medium, be present in the process so like putting the image in there and see what is the limit of where it is cuts and instead of we deciding, allowing the page and the book format to decide that for us and then move the next one, but then also thinking about what image goes next that connects them all together that it moves across was something that we spend a lot of time, working out what works best in terms of the flow, but in terms of the cuts and the folds, it was, yeah, like I'm very much interested in the medium itself, whether it's photography or video or the photo book. I like to see there's more of collaboration with the medium, rather than trying to control it but like allowing the chance to come into it, and that was one of those moments that, like the chance was giving us so many interesting things. We were throwing the images in the format and it was coming up with something quite interesting. I mean, in the layout.

- Thank you, Nita, that's a great question. It's interesting Hoda like the, I'm absolutely fascinated by the, there's an element to the, there's portraiture but there's also such a depth to the relationship that you developed between yourself and the place and these people, to the point where they were sharing their visions of this force with you in those drawings, so can you tell us a little bit more about developing that trust and that immersion in that community through this project?

- Absolutely, that's something that is really important to the process for me like I can't, I realised early on that I'm the worst photographer when it comes to short, limited commissioned projects. If I'm giving an editorial task, I really can't do it, I've proven that to you, to other people who thought I would be able to, because I need time and time is a very important element for me and it's only with time that comes trust and knowledge, especially if I'm working with sensitive topics as such, and for me, the book is based on incomplete knowledge, you know, like when you think about history, history is never completed and when you work with the locals, it's all based on oral histories and also what you read has a history, a lot of the locals tells you that that's not true, so how could you place yourself within that context as someone that holds the truth of the story or the narrative? So it was something that I like only for me with different projects as well, it can be possible and happen if the people are like the subjects or I don't like to use the word subject, it's the collaborators are actively involved in the process of making it so it was sitting in cars, moving with them, and them taking me to places to take pictures of the stories they were telling me about, and also with the shamans, it was just returning so many times because you're not allowed to film actually, or take pictures of the actual ceremony, it's sacred to them, and for us, it was more about, like often with all my other works, it's like staging and performing real stories but with the real people in real places but it's just reenacting it for the camera in some ways. So there's more truth in that for me than me clicking and run and taking pictures of things when the camera is hidden. In fact, for me, it's like the photographer and the camera has to be so present in the work and I try to make it present in the images as well, to bring out the constructed nature of all these realities that we reflect in our photographs in a way.

- Yeah, that's so, that factor of time and just building, building up that knowledge and the, but then, I love that concept of knowing what you can't learn and knowing what you don't know and the different layers of the narratives. Does that relate to why you were determined not to present a sort of linear narrative within the story because you presumably could have done that if you chosen to?

- Yeah, it just like the traditional style of documentary making and storytelling, not just, it's the conventional structure that you start with, there's a beginning, there's a story, there's an end and a conclusion. But, you know, like the "Speak the Wind" is more about, like that's what the title is for, to reflect the impossibility of the story. It's more like, the book is about what's not there, to be honest, like basically everything that the story is about is not present in the book, so it's more about the effort of the author to tell an impossible story, basically. So for that I couldn't even like, because it's very much multidirectional, it's like being dragged from one place to another, one person tells you this story and another one contradicts it, so there's no linear order in that and it's just basically reflecting the experience. I want people to experience something, something that is basically treating magic as the real and trying to move beyond the exoticness of the place but then bring into attention something about our human, humanity and also our relationship to the land, how our identities are shaped by the places that we live in or born in.

- And so how do you translate the impossibility to an exhibition? Hoda, just tell us a little bit about how that's going for your exhibition at Monash Gallery of Art and I suppose what you've discovered about the exhibition form as opposed to the book form in this sort of translation exercise?

- Yeah, it's a very challenging process because like when I was doing the book, I was trying to think what the book can do that an exhibition cannot do, so how to use that as a way of making the work, and now trying to think what the exhibition can do that the book couldn't do. So there's this film element that is just about to be completed with the sound design and colour grading that I spend almost the year editing it, and the film will be shown for the first time here, opens here and then soon after that, in Italy and then hopefully travel around the world, but then also to kind of move here because once you spend so much time making that book, the structure and format of the book is so present in your mind, and then when you want to translate it into an exhibition format, it's just almost impossible to get out of it, but then I ended up making it my cut of the MGA space and then placing all the images around it and play. I'm excited about what's about to come. I think finally I arrived at a point that I'm really happy with the choices we made, and I can't wait to share it with everybody. It's been challenging but we're there now.

- That's so good to hear. Did you find new things in the images that you've taken as a result of that process?

- It's a, yeah, it's a very different way of treating the images like instead of which goes beyond the format that we chose for the book and then looking at them in a very different mode of presentation, it also, because the possibilities are endless with, when you have hundreds of images, you can choose so many different ways of presenting it so it's exciting to kind of look at it and approach it differently again.

- And did you introduce a new selection? Did you go right back to the beginning in making the exhibition or did you sort of treat the material as being the layer that you extracted for the book?

- No. I decided to stick with what went into the book rather than bringing images that we left out, because I think that once the selection is made, that's the work and the rest is outtakes that hopefully, one day, in a larger exhibition, you can present it as other material that didn't make it to the series, but I'm working with what's in there, yeah. It's only the film that is a new element.

- Oh, that's so, I can't wait to, I can't wait to see it, Hoda. It'll be-

- Thank you. make it to Melbourne for it.

- Yeah, I hope so too, and all our, anyone coming who's in Melbourne at the moment, look out for the show and so, Hoda, we've got a few minutes left and I'd love to hear, you know, we at the National Portrait Gallery, all our finalists are now, winners of the NPPP become part of the NPG family, and we're always so excited to follow travels around the world and the next chapters for all of our artists and so I'd love to hear what's next for Hoda Afshar in 2022 and beyond.

- Oh, oh my God, but I actually takes on too much at the moment and there's a lot happening. I'm excited about it. There are two big projects for 2023 that I'm not allowed to share at this stage, what they are, but there are quite exciting for me and soon will be shared. After showing, opening the exhibition at MGA, I've got two exhibitions of "Speak the Wind" in Vienna and Italy, as I mentioned, and hopefully more opportunities for it to be shown around, and then I've got a show as part of the Aichi Triennale in Japan and I think June and a few others which keeps me quite busy, but then I have to, in the second half of the year, I've got to getting to making new work for those other projects for the following year.

- Oh, that sounds so exciting and you, I suppose for the last two years, have you been able to get back to around much, have you, are you looking forward to continuing your ongoing project of that, those visits and that photography?

- Absolutely, I haven't been able to go back. This is the longest I've gone without seeing my family. It's 2 1/2 years now, and it's because of the pandemic, the borders were shut, and I tried when I was in London, I went even to the airport and from there, they send me back, they said the borders are closed, but I'm hoping to go if I can, during the break in midyear and between June, July, and I'm really hoping that the borders remain open till then, but we will see. And, of course, when I return, I will continue making pictures there as well.

- Oh, Hoda, it's been such an absolute pleasure chatting with you.

- [Hoda] Thank you.

- Completely absorbing and wonderful to see some images and hear you reflect on "Speak the Wind" and your experience in the last two years. Thank you so much and handing back to Gill to finish off the programme. Thanks again, Hoda.

- Thank you for having me. I really appreciate it, and thanks to everyone who joined in. I can't see it, but thank you.

- Thank you so much, Penny, and thank you, Hoda. We have had over 80 people who have just been enthralled by looking at your images and making lots of amazing comments. We've had some comment from Dee who was saying that she feels that the, she feels very privileged that you've shared the spirit and connection of the people that you've been photographing but also that she feels your spirit and connection with the place through the images, so I thought that was a really nice comment to finish off the programme. So thank you and we will send you all of everybody's amazing comments at the end, Hoda, so you can go through them and feel the love from the audience today. Thank you to everyone who joined us. Thank you so much for supporting the arts and for supporting the National Portrait Gallery. We have a whole raft of virtual highlights to us that have kicked off again. If you haven't already joined in on our Tuesdays at 12:30, please do jump on our website, portrait.gov.au and check out what's coming up. We can't wait to continue to share all forms of different forms of portraiture with you through these virtual programmes in 2022. Also coming up, which you'll probably start to see filtering into our virtual programmes, is our big exhibition that's coming from MPG, London, National Portrait Gallery of London, Shakespeare to Winehouse is opening in March, so you'll start to see some programming trickling in around those amazing portraits from the National Portrait Gallery, London, some of which have never been seen in Australia or unlikely to be seen again. So please do jump on our website, portrait.gov.au once again, and our social media channels @portraitau for all the information about that. Thank you, everybody, and I look forward to seeing you all again, very soon. Stay safe and stay well. Thank you, bye-bye.

Related people

Related information

National Photographic Portrait Prize 2015

Previous exhibition, 2015The National Photographic Portrait Prize exhibition is selected from a national field of entries, reflecting the distinctive vision of Australia's aspiring and professional portrait photographers and the unique nature of their subjects.

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

Support your Portrait Gallery

We depend on your support to keep creating our programs, exhibitions, publications and building the amazing portrait collection!