For far too long, the accepted history of art was one of white male achievement. If women were mentioned, they were usually cited as subjects, not creators. Even though there is clear documentation of female artists working professionally across Europe from the 16th century onwards, and Indigenous women have been central to cultural expression for millennia, in the first editions of the most popular art-historical textbooks of the 20th century, E.H. Gombrich’s Story of Art (1950) and H.W. Janson’s History of Art (1962), the only women mentioned are those painted by men. Similarly, in the renowned art historian Kenneth Clark’s The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form – which was first published in 1956 and covers art from Ancient Greece to the 1930s – not a single female artist is mentioned. In the index ‘woman’ is categorised under ‘condemnation of’; ‘crouching’; ‘old’; ‘nudes of’; ‘prehistoric’; ‘statues of’; ‘virgin’. That a woman might be creative is not discussed.

For centuries, women had no political agency and if they had artistic ambitions, they were barred from the traditional training so necessary to a professional artist – such as access to a life studio, an art school, an apprenticeship – but still, they persisted. Many women turned to self-portraiture – as they were often the only subject available – and many of them excelled at it. The Italian Renaissance artist Sofonisba Anguissola, for example, was the most prolific self-portraitist between Albrecht Dürer and Rembrandt. Women artists also became adept at portrait painting, especially of other women. Marie-Antoinette’s favourite painter, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, famously painted more than 30 portraits of the French royal family before they met their terrible end and, in 1768, the Swiss portraitist, Angelica Kauffmann was one of only two women among 34 men who founded London’s Royal Academy. In the 20th century, numerous feminist art historians, such as Janine Burke, Linda Nochlin and Griselda Pollock, have explored the rich contributions of women to art history. To see a portrait of a woman painted by another woman is to spotlight a history that for too long was kept in the shadows.

Women artists in Australia had it better than most: they had access to art schools from the late 19th century, were avid travellers and (non-Indigenous) women were granted the vote in Federal elections in 1902. (Compare this to, say, France, where women couldn’t vote until 1944.) In 1907, the First Australian Exhibition of Women’s Work was staged in Melbourne: it went for five weeks, comprised 16,000 displays and was visited by over 250,000 people. Its aim was twofold: to celebrate women and to educate the public in all aspects of their accomplishments. The remarkable Mary Chomley – a charity worker, women’s rights advocate and founder of the Victorian Arts and Crafts Society – was the secretary of the committee who organised this groundbreaking event: the first time the achievements of women had been so publicly showcased. When Violet Teague painted her portrait two years later, Chomley, who was in her 30s, was at the height of her powers. In loose, swift brushstrokes, Teague pictures her as grand and human, elegant and energetic. She looks out with a frank, open expression. In an enormous, lush brown hat and dressed in a eucalyptus-green jacket over a silvery dress, she’s posed, not in a drawing room – which you might expect from her outfit – but against the raw, dry land, beneath a forbidding sky. With one hand on her hip, she’s more than ready for action.

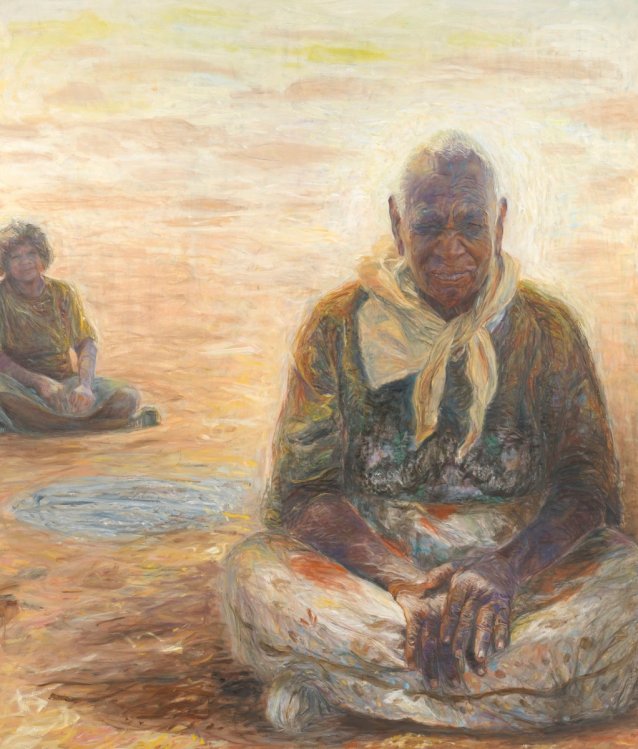

Her portraitist surely matched Chomley’s energy and sense of social justice. Born in Melbourne in 1872, Teague travelled widely, studied painting in Brussels and in London, exhibited at the Paris Salon, became an illustrious portraitist and an expert in Japanese woodblock printing, painted altarpieces and was an accomplished poet and art critic. During the First World War, she also devoted much of her time to French and Belgian war charities. In 1933, she and her sister Una visited the Hermannsburg Mission (Ntaria) on the traditional lands of the Western Arrarnta (Arrernte) people in Central Australia. So shocked were they by the living conditions that they staged a fundraising exhibition and raised more than £2000 (around au$275,000 in today’s money) towards the development of the Kuprilya Springs Pipeline to transport clean water to the local population. The eminent Arrernte artist Albert Namatjira subsequently named one of his daughters Violet.