It’s almost 30 years since I first visited the National Portrait Gallery in London, but I remember the occasion very clearly. I recall what it was like to be in a room full of Tudor portraits, and to marvel at their makers’ precision in rendering the detail of so many bejewelled necks and pearl-studded bodices and doublets. I recollect being overwhelmed by galleries groaning with lush paintings by artists like Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, Thomas Gainsborough and Joshua Reynolds; and spending a good ten minutes each with self-portraits by Gwen John, Laura Knight and Angelica Kauffmann. But perhaps most clear to me is the memory of how it felt to have an encounter of sorts with some of the long-dead people I’m most intrigued by. As NPG London curator Rab MacGibbon observes, ‘the need for social interaction is so fundamental to our nature that it can sometimes override, or at the very least complicate, our perception of a portrait as a constructed representation rather than a living person’. In my case, seeing original depictions of personal heroines like Mary Wollstonecraft, Jane Austen and the Brontës did indeed seem to create what MacGibbon calls ‘a form of imaginative time travel’ and admit me momentarily into another’s presence. I suspect my experience was precisely what Thomas Carlyle, one of NPG London’s founders, had in mind when he wrote of portraits being ‘superior in real instruction to half-a-dozen written biographies’, and of portraiture’s capacity for fostering a ‘human interpretation’ of texts and stories.

Take thy face hence

by Joanna Gilmour, 19 January 2022

In her 1797 portrait by John Opie, eighteenth-century feminist Wollstonecraft looked measured, gentle and contented, and satisfyingly unlike the rabid firebrand her more vicious detractors claimed her to be. The unfinished drawing of Austen made by her sister Cassandra around 1810 seemed way too inconsequential a record of one of the most admired and influential novelists in the English language. But that made it all the more potent a critique of the gendered world Austen occupied: substantial, professional portraits were rarely made of spinsters who lived unobtrusive, hidden lives, nor of writers who made hidden lives their study and whose successes, consequently, were modest in their lifetimes. The drawing said much more than a grand and fancy portrait might, and made me admire its subject’s wit and originality more deeply. I got the same feeling from the portrait of the Brontë sisters, Anne, Emily and Charlotte, painted by their seventeen-year old brother Branwell about 1834. The only surviving image of the three together, the painting had long been thought lost, and was stored folded up on top of a cupboard for years before being acquired by NPG London in 1914. Creased and scratched and peppered with paint losses, it is also inexpertly executed: ‘not much better than sign painting,’ Charlotte Brontë’s biographer reckoned, ‘but the likenesses were, I should think, admirable.’ Yet, as with the drawing of Austen, it’s the painting’s supposed deficiencies that lend it abundance, producing a strong sense of siblings whose imaginations belied the unadorned and unvarying circumstances of their upbringing, and who created such original and memorable fictional worlds despite spending much of their lives in the same Yorkshire village. The portrait remains one of the most cherished works in the Gallery’s collection.

Established in 1856, the National Portrait Gallery, London was the first of the few art museums in the world that focus only on portraiture. The institution sought to embody Carlyle’s point that portraits had more to offer than a record of someone’s features, and that you could therefore be improved, educated or inspired by looking at them. From its outset, the Gallery sought to build a collection of ‘authentic likenesses of celebrated individuals’, and ‘of those persons most honourably commemorated in British history as warriors or as statesmen, or in arts, in literature, or in science’. Debating the proposal for a national portrait gallery in March 1856, members of the House of Lords enthused over how a portrait collection could ‘afford great pleasure and instruction to the industrious classes’, provide ‘a boon to men of letters’, and be ‘useful as an incitement to honourable exertion’. Underlining all this was the stipulation – upheld by the institution until the 1960s – that the subject of any portrait acquired for the collection must be dead, with ‘the reigning Sovereign and his or her Consort’ being the only exception to the rule. Though these concepts might seem antiquated now – and have exposed the world’s small cohort of portrait galleries to perceptions of conservatism, elitism, homogeneity and bias – they coexisted with an unexpectedly modern but equally aged idea that portraits have unique properties, a hybrid character that lends itself to multiple interpretive angles, facilitates a form of connection with others, and enables a more resonant elucidation of history, identity and culture. Central to this approach was the interplay between the portrait itself and the story of its subject, and the question of how artists investigated and conveyed elements such as the character, role or motivations of their sitters. The same philosophy continues to shape NPG London and its Canberra counterpart, the establishment of which was instigated in 1992 by a travelling exhibition designed ‘to bring Australian history to life [and] show some of the strongest and best-known art the country has created’.

Given this shared DNA, the two institutions have often worked together on projects that celebrate our connections with each other, and that seek to reaffirm the ability of portraits to link us with people we can’t ever come into contact with otherwise. This characteristic seems to have become so much more salient recently, when distance, isolation and disconnection have been the new, rigorously enforced normal, and where in-person encounters with artworks seem a distant memory. But unprecedented times have their upsides, and NPG London has turned the temporary closure of its St Martin’s Place home into a truly rare opportunity to distil its unparalleled collection of more than 215,000 works into an international touring exhibition that will be shown in Canberra in autumn. Unlike other NPG London exhibitions to have travelled here, however, Shakespeare to Winehouse: Icons from the National Portrait Gallery London departs from a single-artist or chronological rationale and groups its works according to a series of themes that are intrinsic to portraiture – including power, fame, identity, love and loss – but which evade the constraints of style, medium and time.

Using this framework, Queen Elizabeth I – bristling with jewels and symbolism in what is known as the ‘Phoenix portrait’ of c. 1575 – can sit in seamless, visual conversation with a holographic portrait of Elizabeth ii, created more than 400 years later. A selection of self portraits spanning a similar timeframe situates painters including Kauffman, van Dyck, Reynolds, David Hockney and Lucian Freud in a continuum that demonstrates the longevity and centrality of the practice of defining creative style and professional identity through the scrutinisation of self. Similarly, portraiture’s role in making statements of pride or candour in terms of cultural, sexual or spiritual identity is explored through depictions of sitters as diverse as Winston Churchill, looking domesticated rather than statesmanlike in a painting by Walter Sickert; and writer Radclyffe Hall, who is mostly known for her semi- autobiographical work The Well of Loneliness, an unflinching portrayal of lesbian sexuality that was banned shortly after its publication in 1928.

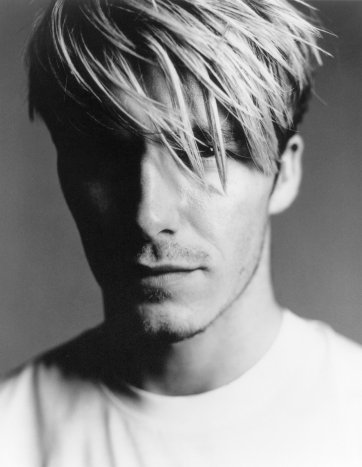

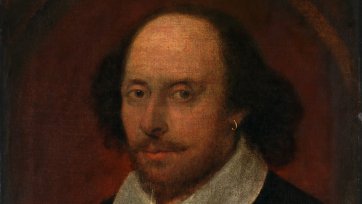

In addition to works I suspect I would sell my soul for – the aforementioned painting of the Brontë sisters, for instance – Shakespeare to Winehouse will also feature works blessed with a staggering degree of significance, in terms of NPG London’s history, England’s history and the history of portraiture more broadly. NPG London’s founding acquisition, for instance – a portrait of William Shakespeare painted between 1600 and 1610 – will travel to Australia for the first time. Thought to be the work of John Taylor, who was an actor as well as a painter, it depicts its subject without ostentation, or any of the symbols of ‘genius’ you might expect of a portrait of a literary icon. The only portrait that Shakespeare is believed to have sat for, it was displayed in a London theatre during the Restoration, having become the template for many of the depictions made of the playwright after his death in 1616. Shakespeare’s portrait demonstrates that the fabrication and maintenance of fame through portraiture is not a modern-day, post-photography phenomenon, but a practice that connects individuals as far removed from each other as Nell Gwyn (c. 1651–1687), one of the first English women to make acting her profession, and David Beckham (b. 1975), the footballer whose brand, like Gywn’s, is as much to do with his desirability as his talents.

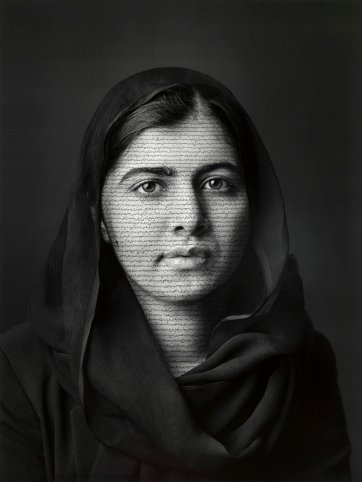

Historical connections between the two institutions are demonstrated by works such as Reynolds’ portrait of Joseph Banks, painted shortly after the sitter’s return from his journey to the Pacific aboard James Cook’s Endeavour in 1771; and a stunning self portrait by designer and artist Doris Zinkeisen, painted in a makeshift studio she set up in her Sydney hotel room during a visit in 1929. The perceived power of portraits to stop time or cheat death, and their usefulness in capturing the presence or memory of those we love and admire most, is explored in works such as Cecil Beaton’s intimate photographs of Greta Garbo, taken in New York in 1946; in one of George Romney’s many paintings of his muse, Emma Hamilton; in Cornelius Johnson’s splendid c. 1640 portrait of Lord Arthur Capel with his wife and five of their nine children; and in Marlene Dumas’ Amy-Blue (2011), a poignant, posthumous portrait of Amy Winehouse, in which we see the singer quietly and up close, in contrast to the clamour, indignity and intrusion implied by the numerous and familiar paparazzi images of her. And the pairing of John Everett Millais’ celebrated painting of artist and suffragist Louise Jopling with Shirin Neshat’s photograph of Nobel Peace laureate and activist Malala Yousafzai, commissioned by NPG London in 2018, makes a powerful statement about the global, trans-historical struggle for women’s rights at precisely the moment when events in Afghanistan have refocused attention on the power and vision of Yousafzai’s work.

These and other groups of works, and the exhibition’s overall approach, MacGibbon explains, will enable visitors to ‘draw out characteristics and features that allow us to explore what people share in common across time and space’ – an exercise which is perhaps more pertinent now than ever. By combining works across media, styles and time, Shakespeare to Winehouse sharpens our focus on portraiture’s unquantifiable qualities: the way it taps into our deep-set curiosities and feelings about other lives, no matter how remote or elevated; and how portraits, though partly about individuality, are more consistently about being human. In so doing, the exhibition acknowledges the foresight of NPG London’s founders, and their conviction that ‘portrait galleries far transcend in worth all other kinds of national collections of pictures whatever’.

Related information

Shakespeare to Winehouse

Icons from the National Portrait Gallery, London

Previous exhibition, 2022From Shakespeare to Winehouse, Darwin to Dickens, the Beatles, Brontë sisters and Beckham, the National Portrait Gallery London holds the world’s most extensive collection of portraits.

Portrait 66, Summer 2021/22

Magazine

The Huxleys, National Portrait Gallery London’s masterpieces, Jennifer Higgie on portraits of women by women, Tamara Dean, Bangarra, Glynis Jones on fashion photographers, and NPG/NGV collaboration.

Virtually yours

Magazine article by Gillian Raymond

Gill Raymond on creating thought-provoking, interactive content to connect to our online community through portraiture.