The subjective nature of scrapbooks encourages us to engage with our critical faculties well attuned. Designed to reflect the subject, the medium ultimately reveals most about the maker. Between clippings painstakingly scissored out of magazines and snapshots pasted with purpose, delicately underscored with handwritten annotations, these reverent pastiches can, in some instances, create an illuminating portrait of a person or a period of time.

The life of Bryant

by Tenille Hands, 3 May 2018

So when a member of the public salvaged a large-scale scrapbook from the inauspicious setting of an opportunity shop, then gifted it to the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia, we were initially dismayed by its unknown provenance. However, further investigation was to reveal we’d received an unprecedented portrait of the professional life and career of Betty Bryant, once Australia’s most famed film ingénue.

The fabled ‘discovery’ of Bryant has given rise to various versions of her story. In one account she was scouted on Bondi Beach by an American producer; in another, a 16 year-old Bryant had a chance encounter with renowned director Charles Chauvel. In yet another, Bryant met screenwriter Elsie Blake-Wilkins after running home during a thunderstorm. The most frequently published story saw a very impressed Blake-Wilkins immediately sweeping Bryant off to meet Herc McIntyre, the American head of Universal Pictures Australia, with subsequent Cinesound Production screen tests and an introduction to Chauvel and his wife Elsa.

Noted showman Charles Chauvel loved drumming up a good press story and made much of his discovery of an entire roll call of Australian stars, including Errol Flynn, Mary Maguire, Chips Rafferty, Peter Finch and Michael Pate. In promoting his 1940 feature film Forty Thousand Horsemen, with Bryant’s role characterised as that of a ‘vivacious French girl caught up in the tragedy of war and living disguised as an Arab urchin behind the lines’, the director declared that 19 year-old Betty was ‘the most important film personality discovered in Australia since Errol Flynn. She has charm, personality [and] vibrant sparkle.’

The truth, as always in the entertainment industry, was somewhere in between. Clippings of on-set portraits from the scrapbook reveal Bryant had already been part of Australia’s most established film production set-up, Cinesound Productions, for a number of years. Unknown to the public until Horsemen, Bryant had in fact had small background parts in productions such as noted Australian director Ken G Hall’s Gone to the Dogs (1939). Intriguingly, she had also shared a scene with a certain Gough Whitlam (her fellow extra), in The Broken Melody (1937).

The scrapbook further illustrates Bryant’s established career in radio and repertory theatre. One page features a black and white portrait in which the vibrant young woman frames her spotlit face with her hands, elbows propped atop a Philips radio. It’s most likely a promotional portrait of Bryant during her long stints on radio serials The Jack Davey Show or The Youth Show. The latter was a national radio series promoted as featuring ‘the finest juvenile talent in Australia, properly trained and brilliantly presented. Fresh young voices … clever young character actors, in a fast moving pot-pourri of music, comedy and drama.’ Indeed, previously unidentified recordings of popular songs of the late 1930s in the NFSA’s collection, such as Bluebirds in the moonlight and It’s a hap-hap-happy day, have now been attributed to Bryant thanks to references to her recorded performances in scrapbook articles.

Another clipping from the scrapbook, an article featuring a quote from Betty herself, clarifies the situation. Taken from a Singaporean newspaper in 1941, it reads, ‘Miss Bryant did not “crash” into filmdom, nor is she a find in the literal sense of the word. “It took me three and a half years before I got my chance in films”, she said; she added that she had to take disappointments at first when told she did not photograph well. She went into radio and the stage before she was given another film test and this time George Keith, well-known cameraman, “shot” her. “It was he who really put me into film business.”’

The ‘George Keith’ mentioned is in fact George Heath, famed Australian photographer and the principle cinematographer for the entirety of Ken G Hall’s film catalogue. Having shot Cinesound’s leading stars, such as Elaine Hamill, Helen Twelvetrees and Shirley Ann Richards, Heath was keenly aware of his role within the industry. He found portraiture ‘a fascinating part of the motion picture photographer’s work, especially when a new girl comes along and sets new and interesting problems’, noting, ‘she has to be photographed with care in order to faithfully record her beauty’. In a 1937 interview with The Western Mail, Heath discussed the process of creating cinematic portraiture, as exemplified in Harry Freeman’s publicity portrait of Bryant: ‘Most faces have blemishes … which are accentuated under powerful lights … brownish movie make up paste is smeared over faces. It gives the skin an even texture which can be lit without accentuating any particular obtrusive spot. Unattractive eyebrows can be improved or painted out and replaced … lips can be reshaped, noses realigned, eye-lashes beaded, and the eyelids can be altered to make the eyes themselves look different but these are elementary artifices for the purpose of photography … the same face, properly lit, should photograph attractively.’

Heath demonstrated the extent of his cinematic expertise with his work as principal cinematographer for Forty Thousand Horsemen. For the film, he assembled an extraordinarily accomplished team of cameramen, including Frank Hurley (Douglas Mawson and Ernest Shackleton’s official photographer); John Heyer (the future ‘father of Australian documentary film’); Tasman Higgins (Chauvel’s principal cinematographer); and, as their apprentice, a young studio photographer by the name of Damien Parer, whose work on Kokoda Front Line! a few years later would win Australia its first Academy Award.

In shooting Horsemen, Charles Chauvel took inspiration from contemporary French cinema techniques. He instructed his team to take on bold camera angles and dramatic lighting, and to move away from the standardised composition of yesteryear. On-set stills and promotional portraits reflected this new style. The majority of stills focussed on Bryant, the high contrast images clearly illustrating her allure. Chauvel was so impressed, he commented that ‘in her close-ups she is very like [Anglo-Indian screen star] Merle Oberon’.

For his part, George Heath stated ‘It is because the camera cannot lie that the photographer must take so much trouble with his composition and lighting in order to obtain not merely a photographic record, but an attractive picture … Light is the medium with which the photographic artist fashions his pictures ... Light properly used can make a face or scene lovely to look at, or, misdirected, it can ruin a picture.’

As if to prove this very point, when senior Commonwealth censors demanded Bryant’s suggestively shot scenes with co-star Grant Taylor be cut from Horsemen, Customs Minister Eric Harrison overruled them, declaring, ‘The love scene in the desert hut had been filmed artistically and with taste’, thus allowing the rousing war epic to be released without omission.

Upon its release on Boxing Day 1940, Forty Thousand Horsemen was an unmitigated success, bringing in 10,000 pounds at the box office in its first three weeks. Inspired by the Chauvel family’s military history, the film undoubtedly played into nationalistic pride, drumming up support for the troops serving in the Second World War.

Within weeks, news outlets were praising Bryant as the breakout star – no mean feat when the film also represented Grant Taylor and Chips Rafferty’s first real shot at the limelight in leading roles. Betty’s portrait seemed to be in every newspaper, with enamoured journalists calling her ‘Sydney’s sun kissed star’ and ‘a feminine cocktail of the grandest ingredients of charm, glamour and personality’. Flipping through the scrapbook for this period, there are images of Bryant on journal covers and even a cut out portrait from Australian Women’s Weekly shot by prominent commercial photographer John Lee.

The film continued to break screening records, becoming the first Australian feature to succeed financially in America. A critic for the New York Times praised Bryant, enthusing ‘whatever it is that leaps across the celluloid barrier, she has’. By mid-January 1941, reports had surfaced in Australian newspapers that ‘still photographs of [Miss Bryant] were sent to Mr Michalove [representative for Twentieth Century Fox]. He showed these to Mr Darryl Zanuck, production head of Fox, who cabled Miss Bryant, offering her a place on the starlet roster at his studio.’

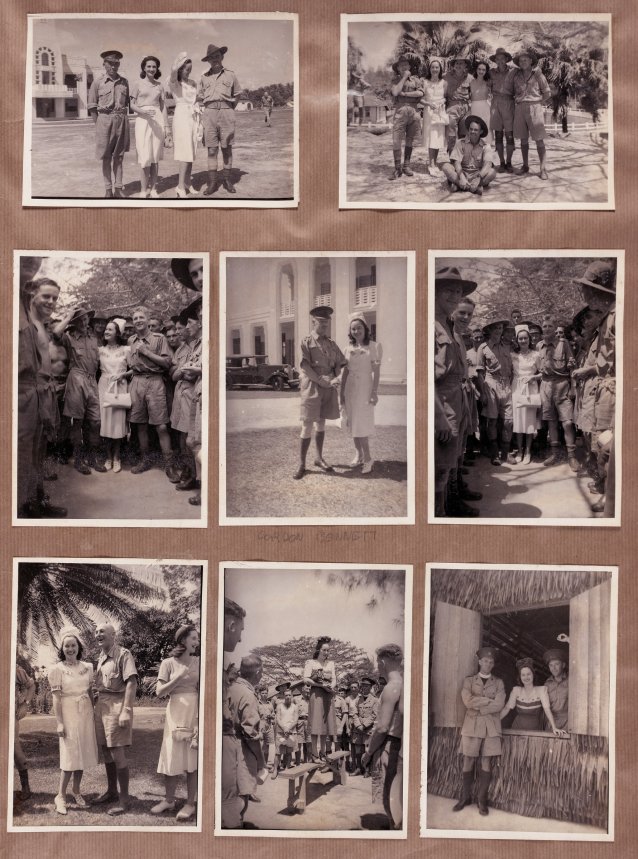

By June 1941, the lessors of the Capitol Theatre in Singapore proposed a vice-regal premiere, promoting the screening as a way of raising war funds for the Red Cross. Charles and Elsa Chauvel thought Bryant was at the peak of her powers and ‘would make a great impression if sent there’. Countless pages of the scrapbook feature Singaporean newspaper accounts of Bryant’s travels. Detailed descriptions of the actress touring camps of armed forces, from Singapore to Borneo, are accompanied by sets of perfectly posed black and white photographs of Bryant with soldiers and notable figures. From here the flurry of portraits and accounts within the scrapbook cease, leaving two large-scale hand-tinted photographs gently folded within the final pages: engagement and wedding portraits, respectively.

Elsa Chauvel’s My Life with Charles Chauvel best describes the sequence of events: ‘Betty not only won all hearts … in Singapore, but she also won the heart of Maurice, then Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s sales manager for the Far East. A whirlwind romance followed during that short week, with Maurice following Betty back to Sydney, where they were married within four days … I feel that her life has had a fairy tale flavour ever since.’

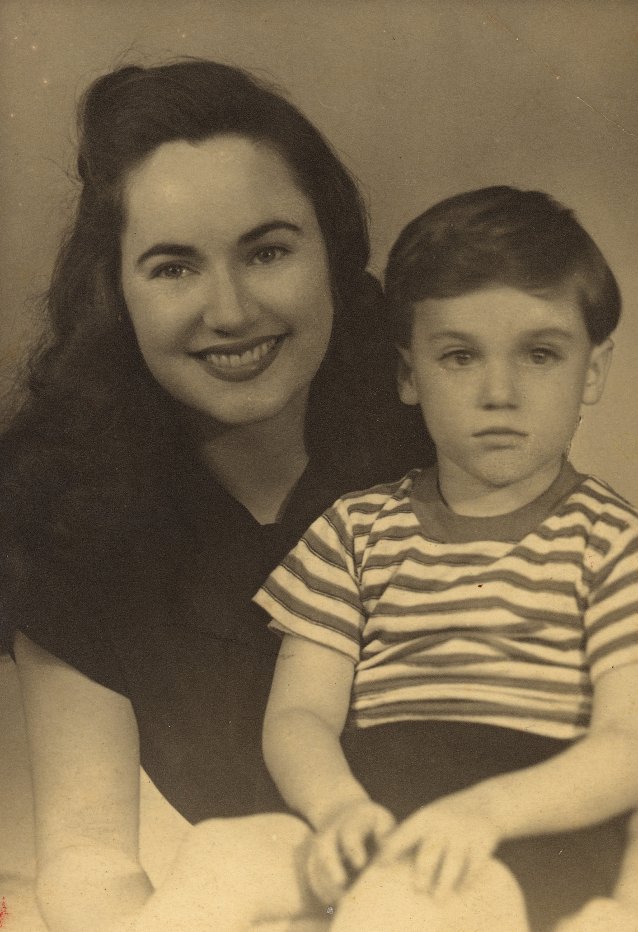

In 1942, upon learning she was pregnant, Bryant withdrew from the role of Greer Garson’s daughter in the American production of Mrs Miniver. A final portrait in the scrapbook is from 1945, and shows Bryant lovingly holding her toddler son Michael and beaming into the camera. Despite later films such as Up in Arms being falsely attributed to her, Bryant was now firmly focussed on her family, friendships and leading the way in sustainable aid work. Elsa Chauvel described her lifelong friend in the 1970s: ‘she still has her youthful gay charm … her greatest characteristic being her generosity and her loyalty to friends, particularly old ones’.

Bryant would go on to form the Foundation for the Peoples of the South Pacific (now Counterpart International) with Australian Marist Brother and friend, Stanley Hosie. She dedicated four decades to tirelessly raising funds and awareness of the educational, health and business needs of communities in over 60 countries. Betty Bryant Silverstein received the Humanitarian Service Award from American First Lady Hillary Clinton in 2000, five years before her passing.

Whilst the original owner of the Betty Bryant scrapbook remains a mystery, an intimate portrait has been left in their wake – not only of the actress, but of said owner: someone who loved her; supported her endeavours; took pride in her many accomplishments and joy in her happiness; and, without knowing it, allowed Betty Bryant’s contribution to Australian film and history to be remembered and celebrated.

Related information

Starstruck

Australian Movie Portraits

Previous exhibition, 2017Striking, beautiful portraiture comes out of the most thoroughly documented creative process there is – filmmaking. In a ground-breaking collaboration the National Portrait Gallery and National Film and Sound Archive invite you into this captivating realm between real and fictional worlds.

Portrait 59, Autumn 2018

Magazine

NPG Washington director Kim Sajet on the Obama portraits, Sarah Ball’s Immigrants, judging the NPPP, Frances Hodgkins, and Picnic at Hanging Rock.

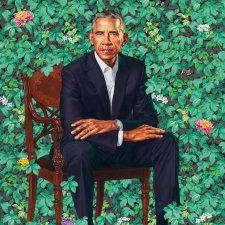

The Obama effect

Magazine article by Kim Sajet

Kim Sajet reflects on two portraits with a power that extends beyond gallery walls.