In early March 1856, the Times reported at length about a discussion in the House of Lords on the subject of a proposal to establish a portrait gallery in London. It was the third time in ten years that Phillip Henry Stanhope, the right honourable gentleman responsible for the scheme, had attempted to persuade the British parliament of the virtues of such an institution, one that would ‘afford great pleasure and instruction to the industrious classes’, ‘be a boon to men of letters’, and, better still, ‘be useful as an incitement to honourable exertion’ in the service of one’s country. In eliciting support for his proposal, Stanhope quoted the then president of the Royal Academy, Sir Charles Eastlake, who had expressed a wish ‘that a gallery could be formed exclusively for authentic likenesses of celebrated individuals’. Stanhope also cited essayist Thomas Carlyle who had espoused the opinion that ‘every student and reader of history who strives earnestly to conceive what manner and fact of man this or the other vague historical name can have been will, as the first and directest indication of all, search eagerly for a portrait’. Portrait galleries, he claimed, ‘far transcend in worth all other kinds of national collections of pictures whatever: in fact, they ought to exist in every country as among the most popular and cherished national possessions’. Stanhope concluded his address with the motion to seek Royal Assent to form a ‘gallery of original portraits’, its collection to consist of likenesses ‘of those persons who are most honourably commemorated in British history as warriors or as statesmen, or in arts, in literature, or in science’.

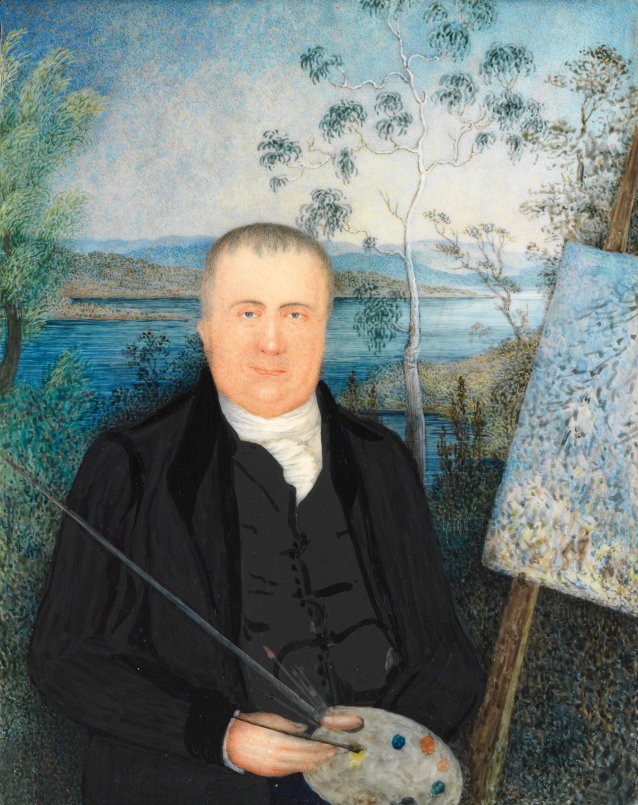

It was unsurprising, then, that when NPG London opened in December 1856 – ‘having been hailed with satisfaction alike by the lover of art, the antiquary, the historian, and the patriot’ – it enshrined the idea that historical records and national identities were constituted of public, masculine pursuits and that portraits, correspondingly, should function much like sepulchres, before which the public could contemplate the deeds of great men. This sentiment was reflected in the institution’s foundational acquisitions: all portraits of sitters who were white, male and dead. The inaugural addition to the collection was a painting of Shakespeare, for instance, and portraits of former prime ministers Spencer Perceval and Henry Addington, Elizabethan courtier and explorer Walter Raleigh, composer George Frideric Handel, and anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce were among the first works acquired in 1857. These set a stylistic tone, too, one that conferred greater status on the type of portraits held in grand houses or by illustrious individuals. Oil paintings primarily, in bust or three-quarter format, the subject posed so as to suggest wisdom or gravitas, or looking thoughtfully, proudly, seriously out at the viewer. These were portraits that lent themselves to preservation and ongoing veneration, not only in their subject matter but in their materiality, oil paint on panel or canvas being more durable than the comparatively inconsequential or ephemeral mediums – watercolour, paper, pencil, shards of ivory – employed by artists producing portraits for private adoration.

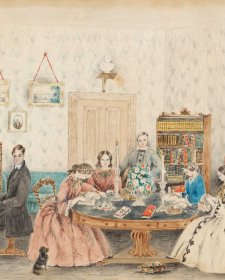

It was the latter variety of portrait, however, that arguably held greater meaning for the middling classes in whose supposed interest the portrait gallery had been established. While, on the one hand, the founding of the institution represented an affirmation of the talismanic aspect of portraiture that underpinned its widespread appreciation, on the other it overlooked the varied and occasionally prosaic ways in which the majority consumed it. Portraits, by the 1850s, were no longer the terrain of the eminent and powerful, and people of all classes had embraced other means of gratifying admiration and affection, longing and loss. The role of creating cherished, authentic likenesses was increasingly the domain of photographers, sketchers, printmakers and others who made portraits for the popular and personal markets, and of practitioners who, for one reason or another, made art without any expectation that their work would be publicly admired or exhibited.

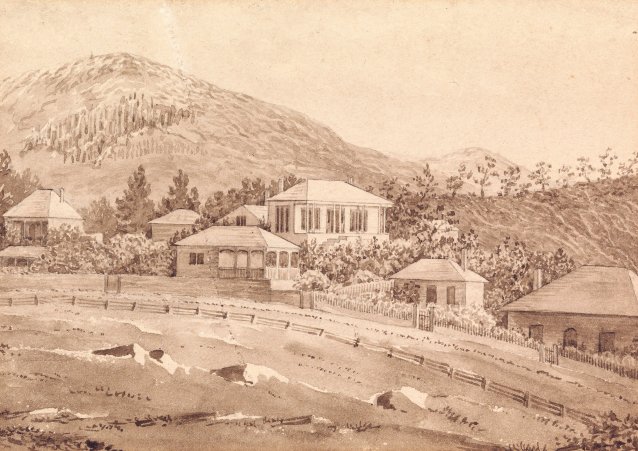

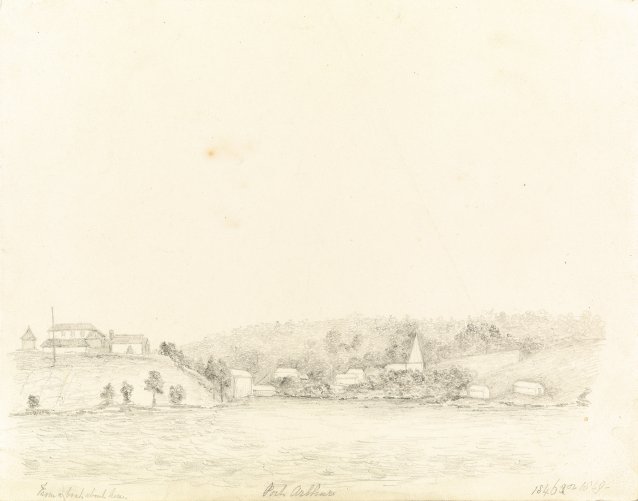

Consider what is known about nineteenth-century Australia from the output of women who were here at the behest of husbands engaged, to varying degrees, in the imperial endeavour. In an especially fortuitous proof of what some have termed the accidental nature of colonial Australian art, these so-called ‘lady painters’ – hitherto a pejorative term – captured people and places that were deemed beneath official notice, or were depicted in artificial, idealised ways. Judged as serving little purpose other than to be as domestic, as demure and as pleasing as their persons, the work of many of these women was for a long time dismissed by historians as a side-effect, and by art historians as decorative or twee. That examples of their work survived has occasionally been accidental too. Many of these pictures were kept for reasons of affection and sentimentality, thereby presenting a counterpoint to cadaverous public effigies in every conceivable way. Writing in the 1980s, art historian Joan Kerr described the ‘added piquancy’ of the work of colonial women artists and the way in which it gives a ‘different dimension to the impersonal perfection’ of the formal or accepted visual record.