Nan Goldin has always declared that she isn’t interested in her own life being ‘susceptible to anyone else’s version of her history’. It is an unwavering life mantra, and one which underscored the peak of her creative expression in the 1980s.

Goldin was born in Washington dc and grew up in Boston. In 1965, aged eleven, she experienced a significant and formative loss, with the suicide of her eighteen year-old sister, Barbara. At the time of her death, Barbara had been struggling to come to terms with her sexuality, alienated in the conservative setting of 1960s suburban America. Ironically, her suicide brought with it its own set of complex taboos.

Conscious of her own awakening as a sexual being, and observing her family’s tight-lipped response to Barbara’s suicide in the weeks and months following her death, Goldin concluded that ‘denial sustained suburban life’. Desperate to escape the suffocating confines of this Pleasantville-like environment, she decided to leave home at the age of fourteen. Her goal: to transform herself without losing herself.

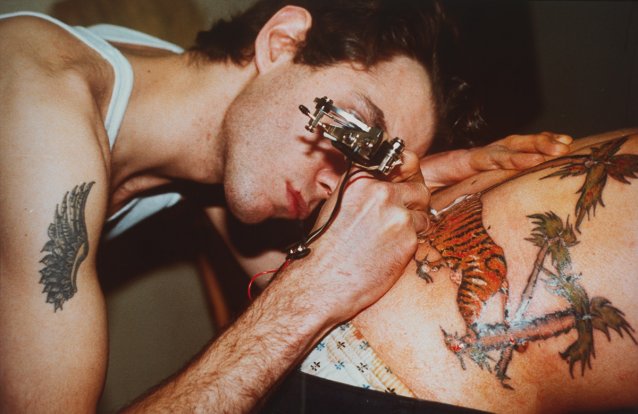

Four years after leaving home, Goldin picked up a camera and started taking photographs. It was the genesis of an œuvre that was to become a kind of portraiture-based autobiography. Goldin was deeply affected by how swiftly her recollections of her sister faded; she has commented that Barbara exists in her mind as a haze of half-remembered conversations and incorporeal memories. She soon realised that photography was a means to retaining a tangible memory of people and events. Goldin states, ‘When I started drinking and going wild and doing drugs, I initially took pictures so that I could remember what I’d done the night before. That was the bottom line. Then it became a more obsessive kind of documenting.’ As a young woman, Goldin’s camera captured a turbulent whirl of wild parties, fierce friendships, experimentation, sadness and euphoria.

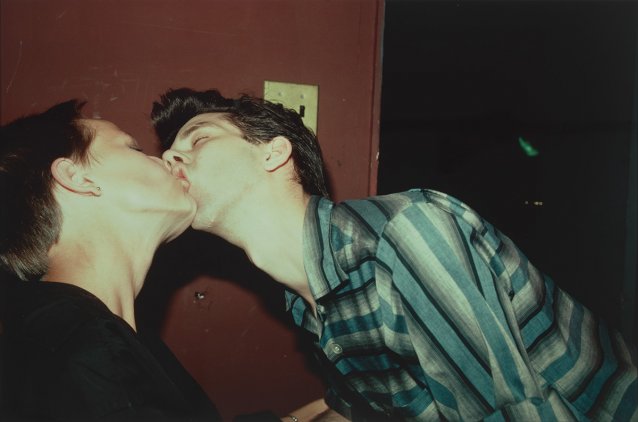

In 1978, Goldin moved from Boston to the Bowery in New York City. Photography proved the perfect tool for exploring and documenting life in her new surrounds, and she captured experiences of drug use, love, sexual experimentation and violence – intimate and immediate moments rendered permanent through their transformation into photographs. Goldin notes, ‘The camera [became] as much a part of my everyday life as talking or eating or sex’. Working as she did within the lurid palette of cibachrome printing, her photographs took on a raw and gritty aesthetic that intensified each captured moment.

The photographs taken in 1978 became the foundation for a public slideshow, later (in 1981) titled The Ballad of Sexual Dependency. In this accessible, affordable and viewer-friendly format, Goldin’s honest, uncompromising images were shown in the clubs of downtown New York City, accompanied by a punk and soul soundtrack that ranged from the Velvet Underground to Nina Simone. It brought The Ballad to life, appearing as an extraordinarily intimate photo album or yearbook – viewers not involved in the particular scenes before them could still relate to the visceral themes presented. Exploring the most intimate of subject matter, Goldin’s photography stripped away preconceived ideas about discretion. And screened amidst the horror of New York’s 1980s AIDS epidemic, The Ballad showed love as being both born in, and having departed from, the city.