You only have to take one look at Nora Heysen’s 1973 painting of Hardtmuth Lahm in the National Portrait Gallery’s collection to think he is the kind of guy you’d like to know, or at least know more about. With his silk scarf, and his crimson pants echoing the ‘Cherry-Bum’ overalls of Prince Albert’s 11th Hussars, he presents an unusually dashing figure for the seventies – an era not notable for elegant male attire, especially in Australia.

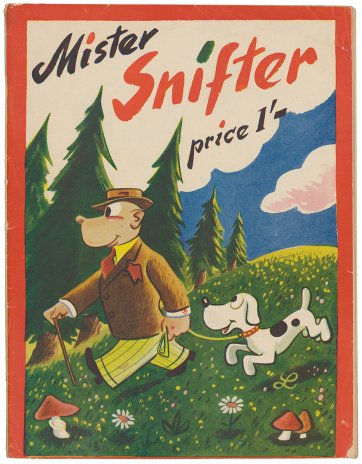

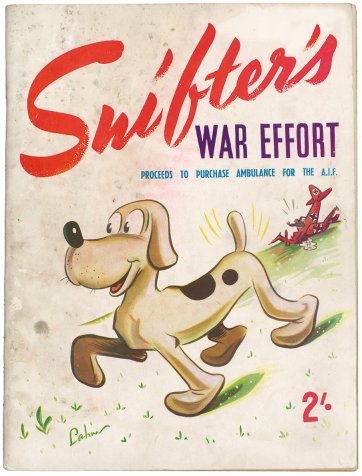

Fittingly, Lahm’s origins were continental – he immigrated to Australia from Estonia in 1928, aged sixteen – and, like another cartoonist of exotic origin, Emile Mercier from New Caledonia, soaked up, and was soon contributing to, popular Australian culture.

The young Hardtmuth studied art at East Sydney Technical College, where his volatile personality earned him the nickname ‘Hotpoint’ (Hottie for short). By the 1930s, his work was appearing in such quintessentially Australian publications as Smith’s Weekly and the Bulletin. In 1937, Lahm commenced his long relationship with Associated Newspapers, supplying covers, caricatures and cartoons for the Sun group of publications.