No other British photographer has made so many memorable photographs as Bill Brandt. He excelled in all fields - social scenes, Surrealism, night photography, wartime documentary, landscape, portraiture and the nude.

So strong was his presence during the middle of the twentieth century that histories of photography often imply that he was the only photographer in Britain during that period. Brandt's endless invention and continual search for ways to expand the medium make his work fresh and timeless.

Brandt came from a cosmopolitan background. Born Hermann Wilhelm Brandt into an Anglo-German family in Hamburg, he was a schoolboy in Germany during the First World War. This searing experience probably contributed to his illness from tuberculosis and treatment in a Swiss sanitorium during his teens. After learning photography in a Viennese portrait studio in the late 1920s, he spent a few crucial months assisting Man Ray in Paris. Here he witnessed the liberating development of Surrealism, as well as the birth of photojournalism in the hands of young emigres such as Andre Kertesz.

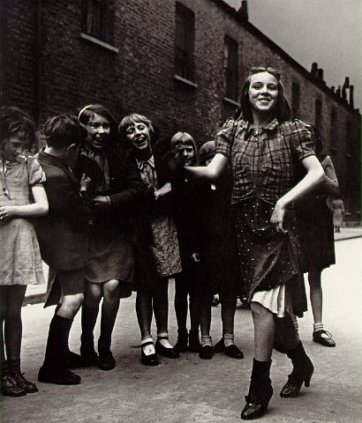

Thrilled with the new possibilities of photography, Brandt settled in London in the 1930s. This tall, blue-eyed, blonde, humorous but intensely private man, with a wonderful smile and a voice 'as loud as a moth', as one friend said, was to become the great documentarian and poet of English cultural and social life. He photographed for the new magazines Weekly Illustrated, Lilliput and Picture Post, and he produced the landmark books The English at Home (1936), A Night in London (1938), Camera in London (1948) and Literary Britain (1951).

In contrast with his contemporaries in Depression-era America, Brandt developed an expressive, high-key style that pushed accepted boundaries of documentary and journalism when photographing the destitute villages and mining towns of northern England. He photographed sharp social contrasts: the glittering surfaces of a rich and imperial city, as well as its humble East End; the coal-black buildings of the northern industrial heartland and the cool, moonlit streets of blacked-out London during the period of eerie calm at the beginning of the Second World War.

During the 'blitz' of World War II, Brandt photographed London by night and followed the crowds into the Underground to escape the bombs. After the war, Brandt's work underwent a shift in focus. He left his documentary style behind and returned to his interests in the surreal. As Brandt himself explained it, 'I think I gradually lost my enthusiasm for reportage. Besides, my main theme of the past few years had disappeared; England was no longer a country of marked social contrast... It seemed to me that there were wide fields still unexplored. I began to photograph nudes, portraits, and landscapes.'

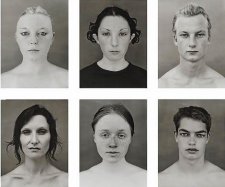

Seeking a lens that would release him from normal visual constraints, which might let him see 'like a mouse, a fish or a fly', he acquired an old wooden plate camera with an ultra-wide-view lens used for police work. He first photographed nudes in looming Victorian interiors, then moved outside onto the beaches of England and France. Brandt's formally plastic and haunting nude studies from this period are now considered to be some of his most innovative work. His long experiment, not always understood or appreciated by his contemporaries, was finally published as Perspective of Nudes (1961).

At the same time, Brandt developed the symbolist potential of photography in a series of landscapes inhabited by the spirit of Romanticism, directly inspired by the writings of poets and novelists such as Emily Bronte. In these works, Brandt defined new territory, indicating among other things photography's kinship with sculpture and modernist abstraction.

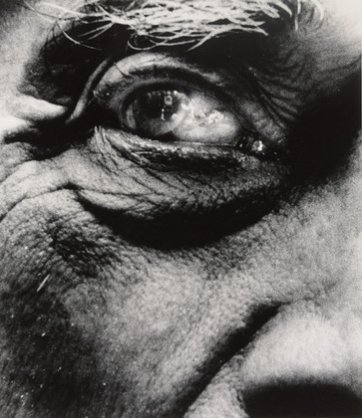

In the 1940s Brandt began his postwar portrait work with Lilliput and Picture Post. Over the 40s and 50s, when he also worked for Harper's Bazaar, he produced many of his great portraits of artists and writers. Himself a much-admired figure of the British artistic and intellectual scene, Brandt produced striking portraits of celebrated contemporaries such as Francis Bacon, E.M. Forster, Rene Magritte and Henry Moore.

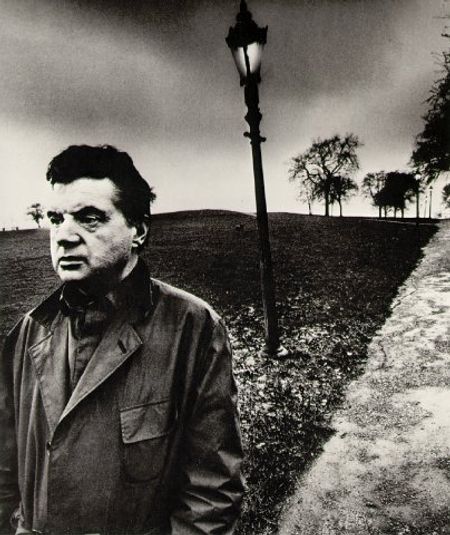

Brandt's later portraits were interpreted through the the Superwide Hasselblad. The 90-degree angle of the lens was exactly right for Brandt's portrait interiors. For outdoor pictures it allowed Brandt to calculate the composition of his three-quarter length study of Francis Bacon and to include the sweeping lamp-lit perspective of Primrose Hill in Camden Town, London. The high-energy vanishing lines and the high-contrast printing style Brandt then adopted gave the later portraits an abrasive edge, highly typical of the 60s and quite dissimilar to the earlier portraits. Brandt continued to take portrait assignments until 1981.

All of the phases of Brandt's career came together in his collection Shadow of Light (1966). In 1969, New York's Museum of Modern Art honoured Brandt with the first retrospective of his work, which was followed by several solo shows at museums and galleries in Europe and the United States. In 1981, two years before his death, the Royal Photographic Society inaugurated its National Centre of Photography in Bath with a Brandt retrospective. Brandt's extraordinary contribution to photography continues to invite interpretation from fresh perspectives, and to fascinate international audiences.