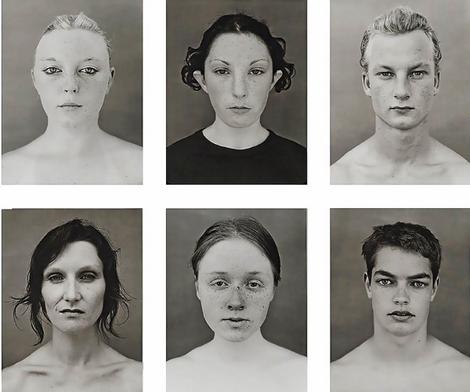

In his recent project 123 Faces, Simon Obarzanek displays a penchant for a detached type of collecting. Over the past three years he has amassed an archive of some four hundred faces, all full frontal head and shoulders 'portraits' taken against a neutral background. Slightly disconcertingly, he coolly describes his compulsive 'hunting around for faces'; he has no interest, he says, in the character traits of the subjects he shoots.

Sixteen photographs from this series are included in Contemporary Australian Portraits. These loosely relate to works by Cherry Hood, Ricky Maynard and Siri Hayes in which the identity or appearance of an individual sitter contributes to a universal concept or quality when viewed as part of a series.

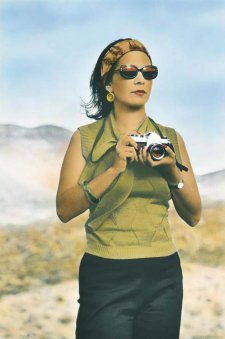

Hayes' photographs of mothers in the pose of Raphael's Sistine Madonna document everyday experiences of motherhood. Seen as a group the quotidian is augmented with religious connotations, a sense of the divine. Cherry Hood's sculptured heads place faces into a context that recalls displays of ancient busts in Roman museums. They employ repetition of form and method to refer to a particular tradition in portraiture rather than a single person. In Returning to places that name us, Ricky Maynard photographs Wik elders to emphasise traditional Ngarinyin culture, exploring the relationship between the group and the 'place' which provides their 'name' and identity.

Obarzanek is a formalist. His interest in each sitter lies in recording, compiling and ultimately re-presenting the face at its most basic, as a shape, a uniform series of elements that don't come in any standard format, almost an abstraction. He is very interested in the effects and use of light.

The photographs are all taken outdoors. Lurking in the crowd at the 'Big Day Out', a platform at Sydney's Central station or the Royal Easter Show he chooses structures, physical attributes not personalities, as the subject for his images. His plan is to empty, not to reveal. He refers to his faces generally, by descriptions, not names. For example, 'Horse woman', 'Ukrainian girl', 'Freckled girl' or 'Bearded man'.

Parallels can be drawn between 123 Faces and the work of photographers including August Sander, Diane Arbus, Richard Avedon, Bettina Rheims, Thomas Ruff and Chuck Close. Each of these has made series of portraits of anonymous sitters (or sitters identified only by their first names), using a standard format, which have challenged fundamental historical presumptions about the ability of photography to reveal personal or individual truth in a single image. Richard Avedon, also a formalist, who famously made series of portraits against a white background, once commented; 'You can't get at the thing itself, the real nature of the sitter, by stripping away the surface. The surface is all you've got'.

There is a refreshing candour in the lack of psychoanalytical probing in Simon Obarzanek's photographs. He spends five minutes with each subject and generally does not know anything about them. How, in half a roll of film, could he present anything more than a surface, the skin of those who sit for him? Yet, as anonymous and general as the photographs may be, each of his faces is unique. In displaying them as a group, in a grid or in a straight line, paradoxically it is individuality, not sameness, that emerges.