In the course of a happy weekend at Sandringham in 1930, King George V told his former Aide-de-Camp, William Birdwood, that he believed he would have made an excellent Governor-General of Australia, ‘the more so since after my close association with the Australian troops many people had come to believe that I was an Australian by birth, and not simply by adoption’ as Birdwood put it in his autobiography.

The King had badly wanted to install Birdwood as the second occupant of Yarralumla, and Birdwood had felt an equivalent ambition to move in. However, Australia’s first Catholic prime minister, James Scullin, had gone to England in 1930 with a mandate from the Labor Party to secure an Australian, for the first time, as the next Governor-General, and with various degrees of regret, perhaps, on all sides – for Scullin had been ‘very nice about me personally’, Birdwood recalled – Isaac Isaacs was nominated for the role instead.

The subject of one of relatively few twentieth-century portraits in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery to be acquired under the criterion of ‘Australian by birth or association’, William Riddell Birdwood KCMG KCSI KCB DSO, First Baron Birdwood (1865– 1951) commanded the Australian Imperial Force throughout the First World War. Born in India (where he was to spend more than half his life), he was educated in England, taking his military training at Sandhurst before returning to fight on India’s north-west frontier. From late 1899 to mid-1902 he served on Lord Kitchener’s staff in South Africa. Surviving a severe wound, he was Mentioned in Despatches five times; he received the Distinguished Service Order in 1908 and was subsequently promoted to major general. From 1906 to 1910 he was Aide-de- Camp to Edward vii, the popular king who gave his name to Britain’s last golden age.

During the Boer War Birdwood had come to know many Australians and New Zealanders amongst the mounted men for whom he was responsible. So it was that when the First World War began and Kitchener ‘tapped’ him to command the Australian and New Zealand forces bound for Europe, Birdwood found himself ‘in the seventh heaven of delight’. He met his men in Egypt at the end of 1914; four months later they landed at Gallipoli. Here, over nearly eight terrible months in which he was wounded early on, Birdwood regularly visited the front lines and took audacious daily swims in the place that he had named Anzac Cove.

‘His delight was to be out in the field among his men’, Charles Bean wrote. For his part, ‘Birdie’ doubted that a commander had ever lived more intimately with his men than he had had to on the fateful peninsula, and judged that ‘nowhere in the world would it have been possible to find better, braver or more forthcoming comrades that I was blessed with in the Australian and New Zealand Forces.’ Though he saw all attempts on Turkish positions fail, Birdwood was not disposed to retreat. Overruled, however, he oversaw the withdrawal – in itself a singular success – in December 1915.

In early 1916 the ANZAC Corps was split in two. Birdwood accompanied I ANZAC Corps to France, and directed its operations throughout 1916 and 1917. Late in 1917, he took command of the Australian Corps when it was formed from the five aif divisions. After John Monash succeeded him six months later, Birdwood took command of the British Fifth Army, but retained administrative responsibility for the Australian Imperial Force. Despite his having led them through awful Western Front actions, not least Bullecourt, Birdwood continued to enjoy an unusually high level of respect from Australian soldiers. Historian Peter Stanley believes that the casualties suffered by Australian (and other) troops in Gallipoli and France are largely attributable to how ‘flummoxed’ Birdwood and other senior British commanders were by contemporary industrial warfare. Every man there, Stanley points out, was ‘learning on the job’ – from jejune recruits to seasoned campaigners, such as Birdwood, in their fifties. The carnage notwithstanding, Australians liked Birdwood because he valued them for themselves, and had the sense to realise that they required a different style of leadership from English or Indian soldiers. In 1919 he was created First Baronet Birdwood; in 1920 he was made a general in the Australian Military Forces, and in 1925 he was made field marshal.

After the war, Birdwood’s elder daughter Constance (Nancy) married a West Australian grazier, Colin Craig. Birdwood and his wife were keen to visit her, and he also wanted to ‘see something of my old comrades in their homes’. He was warmly welcomed here; in fact, he felt that he was rarely as happy as when he visited the Antipodes, complaining only that at times, the enthusiasm of his old friends was so ‘violent’ that he and Lady Birdwood feared being killed by kindness. An avid tiger hunter, in his spare moments he relished the fruitless pursuit of kangaroos: ‘It was worth anything to have those gallops over country which almost everywhere was such excellent going. What a life for a carefree man, with a good horse between his knees!’ He was also profoundly impressed by Australian working dogs: ‘Can one not imagine the grief of the whole family when such a dog goes the way of all dogs, and all too soon has had his day,’ he wrote.

Given command of the Indian Army in 1925, Birdwood retired from military life in 1930, after which, having missed out on the governorgeneralship, he became Master of Peterhouse College, Cambridge. Close to the epicentre of the almost inconceivable splendour of the Coronation of King George vi in 1937, he rode firm and upright behind the dazzling Royal coach in his capacity of Gold Stick-in-Waiting. The following year, when he represented England at the funeral of his forgiven foe, Kemal Atatürk, he was elevated to the peerage. Barons are entitled to choose the place names in their titles, and Birdwood chose to style himself First Baron Birdwood, of Anzac, and Totnes, co. Devon. The hereditary title was the pinnacle of his countless honours – amongst which were a handful of honorary doctorates from universities including Melbourne and Sydney. His grandson Mark, the third Baron, born in 1938, has no son.

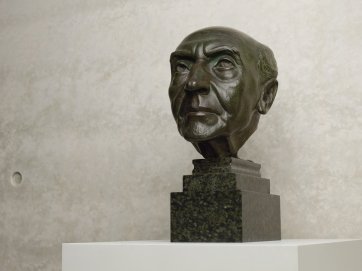

It was in 1937 that the young Sydney-born sculptor Barbara Tribe (1913–2000) made her imposing bust of the septuagenarian warrior. Barbara Tribe had enrolled at East Sydney Technical College at the age of fifteen. Having studied with Rayner Hoff, in 1935 she became the first woman – and the first sculptor – to win the New South Wales Travelling Art Scholarship. In London, when her scholarship expired she persuaded the director of Selfridges department store to let her create portrait busts on a modelling stand in the China and Porcelain Department. Though Birdwood came to her Kensington studio to pose, bristling with medals that he had taken out of the bank for the purpose, Tribe created a portrait head of the Birdwoods’ grandson at her very public workspace in Selfridges. Later, she visited the couple at Windsor Castle.

Having worked on the Australian Wool Pavilion at the 1938 Empire Exhibition in Glasgow, modelling a merino ram that was repeated as a frieze around the exhibit, throughout the second world war Tribe remained in England, working in the Inspectorate of Ancient Monuments. Afterwards she moved to Cornwall, where she taught part-time at the Penzance School of Arts for forty years. Returning to Sydney for a visit in 1966 she found her achievements forgotten, but over the 1990s the collector, art patron and great benefactor of the National Portrait Gallery, John Schaeffer ao, helped to revive her Australian and international reputation. Schaeffer subsidised the publication of Barbara Tribe: Sculptor (2000) by Patricia McDonald, from which some of the information in this article is taken.

Barbara Tribe’s portrait sculptures are represented in the Australian War Memorial and the National Gallery of Australia as well as the National Portrait Gallery, which acquired her serenely interrogative bust of Stanley Bruce in 2000. After the sculptor’s death, the National Portrait Gallery was invited to identify desirable works from her estate. The jewel amongst these, the life-size bust of Birdwood, now occupies a position of command in the Schaeffer Gallery. Convincing and piercing eyes (created with small lumps or spikes positioned in the bored-out pupils, which catch the available light) are characteristic of Tribe’s heads. So it is that the eyes of the bust of Birdwood seem to appraise the room, on the lookout for opportunities, enemies, prey or any honours that may have eluded the man in life.