In the limited pharmaceutical world of the mid nineteenth century, laudanum was everybody’s choice of poison. This easily procurable cocktail of opium and alcohol was cheaper to buy than a bottle of gin and used for the treatment of any number of conditions, mild or malignant: applied in the case of a fractious, teething infant; prescribed for period pain, coughs, colds, or insomnia; and used to alleviate the throes of cancer or consumption.

A trawl through newspapers of the time will also occasionally reveal its efficiency as a method of suicide. It was a factor in a number of deaths reported in Tasmanian newspapers in the 1840s, including that of painter Henry Mundy, who ended his life with an overdose of laudanum in a Hobart pub.

‘An artist of considerable ability, and very respectably connected in the colony’, Henry Mundy (c. 1798–1848) flourished in Van Diemen’s Land during the late 1830s before his success as a portrait painter withered in the economic woes of the succeeding decade. The final years of his life, according to acquaintances, were marked by alcoholism and ‘irregular habits’ as well as the ‘occasional state of temporary insanity’ that was declared to have ‘urged him to the commission of the awful deed’ of suicide in March 1848. Mundy had checked into the Ship Hotel on Collins Street and retired to his room after a couple of ales and a cigar. He died soon after being found ‘insensible’ on his bed the following morning with an almost-empty laudanum bottle on the table beside him and in his pocket a letter demanding payment of a debt. An autopsy conducted in the same room later that day revealed his stomach to contain an amount of opium ‘sufficient to cause death’.

The sordid facts of Mundy’s demise somewhat overshadow the grace of his achievements in the years preceding it, years when he created paintings now counted among the finest examples of colonial Australian portraiture. Henry Mundy was born in London around 1798 but details of his background are unclear. A newspaper report of his death describes him as having ‘visited France, Italy and other Continental countries in the study of his profession’, suggesting that his instruction in art was thorough and that he had the means to afford it. Whether by breeding or training, however, Mundy was seemingly not fitted enough to cut it as a painter in London and chose to move a socially mutable place where his skills would be more than acceptable. His arrival in Van Diemen’s Land in 1831 coincided with a change in flavour effected by the swelling numbers of free settlers who came to the colony to remake themselves in the guise of gentry. The fortunes of many flourished in the 1830s through the success of farming enterprises lubricated by an inexhaustible supply of convict labour.

By this time, the policies of lieutenantgovernor George Arthur – a moralising military man versed in the administration of British settlements – had cleansed the island of what were held by eager colonisers to be its biggest blights. He introduced schemes to perfect the colony’s function as a prison, establishing the penal settlement at Port Arthur in 1830. Arthur’s rigid approach combined with the spread of settlement diminished the strength of the escaped convicts and bandits who had been lording it over unoccupied parts of the island, and his governorship has been noted for the record number of miscreants despatched by the gallows in the early years of his term. It was Arthur too who attempted to resolve the conflicts between dispossessed Indigenous Tasmanians and the colonists driving them from the juiciest, most profitable pieces of their homeland. His efforts ended with the instigation in 1831 of the ‘friendly mission’ of George Augustus Robinson, which by the middle of that decade had persuaded Aboriginal people to accept relocation to Flinders Island, with ultimately catastrophic consequences.

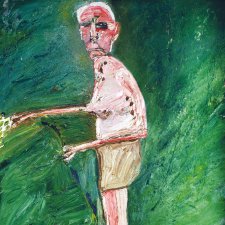

As was so for a number of his artist contemporaries, Mundy arrived in a place ripe for delineation and his portraits – like the works of Benjamin Duterrau (1767-1851), Thomas Bock (1790-1855), and Thomas Griffiths Wainewright (1794-1847) – give flesh to underlying narratives of the island’s history. These artists created a complex visual record which often belies the deeply dark or merely unsavoury underpinnings of the prosperity enjoyed by the colony’s free settlers in the boom years of the 1830s. Duterrau celebrated the efforts of Robinson and the Indigenous leaders associated with him in the first history paintings created in Australia.

Bock’s exquisite handling of line was deployed in the documentation of executed criminals or still-emboldened bushrangers in the dock. And as a free man Bock, like Wainewright (another artist who came to Hobart a convict), made fine portraits of the island’s citizens. Like Bock and Wainewright, Mundy’s practice capitalised on the pretensions of free settlers who liked to mark their distinction from the ex-convict ‘lower orders’ by embroidering the new world with niceties. Fine estates with fine houses. Gardens. Hedgerows. And portraits.

Accordingly, when Mundy first arrived in Van Diemen’s Land it was to take up a teaching position – earmarked for Duterrau and his daughter – at Ellinthorp Hall, a girls’ school near the town of Ross. For several years, Mundy taught drawing, French and music at this school, touted as a provider of ‘every branch of Female acquirement’, and situated ‘expressly with a view to … the comfort and improvement of Young Ladies.’ Despite Lady Jane Franklin deriding Ellinthorp as a place more ‘noted for its balls and concerts and matchmaking’ than its reputation as a school, it was one of very few places in Van Diemen’s Land suitable for those wishing to make ‘ladies’ of their daughters. It attracted the patronage of the island’s most successful families and, for its urbane, portraitpainting drawing master, thus secured access to a fertile source of subjects.

Mundy is known to have painted at least one of his pupils – Mary Ann Lawrence (1821-1881), the daughter of a Launceston landowner. His portrait of Mary Ann was painted around the time of her engagement to pastoralist Francis Henty in 1841, the year that also saw the death of Mary Ann’s father and Mundy’s creation of a portrait of her mother, also Mary Ann, shown in the garb required of mourning wives.

Lady Franklin may have been correct with the matchmaking line at least, for by the time Mundy left Ellinthorp it was with a wife said to have been one of his pupils. Lavinia Lord, the daughter of the erstwhile commandant of the Macquarie Harbour penal station, was sixteen to Mundy’s thirty-six when she married him in 1834. By 1838 Mundy had relocated to Launceston and established himself as a landscape painter, portraitist and music teacher. For a few years, his business thrived.

The island was awash with the well-to-do and the new lieutenant-governor, Sir John Franklin, and his lady were doing their best to cultivate the arts in the colony, Lady Franklin even inviting Mundy to create works for her (invitations, however, that he declined). Mundy enjoyed the patronage of other notables, as demonstrated by the commissions he completed for men such as Thomas Archer (1790-1850) the owner of the estate named Woolmers, south of Launceston, and other slices of the district’s farmland. Mundy was paid one hundred and eighty pounds for his paintings of Archer; his son, Thomas William Archer; and Thomas William’s wife, Mary, all painted around 1841. Like the pictures of the Lawrence women, these are portraits in a stately style – Thomas junior, tall and brooding with his frock coat and sideburns; Mary in her finery; and Thomas senior, imposing, ruddy and corpulent.

Mundy’s portraits of Archer’s daughter Martha (1821-1853), and her husband Robert Kermode (1812-1870) – a landowner, politician and lobbyist for the abolition of convict transportation – date from around 1840. Robert was the son of William Kermode (1780-1852), a merchant who emigrated to Van Diemen’s Land in the 1820s and established a farming property, Mona Vale, near Ross. Robert spent his boyhood on the Isle of Man before coming to Van Diemen’s Land as a teenager to assist his father in the management of the estate. Robert no doubt bolstered the family’s status with his marriage to Martha in November 1839, a match by which two of the colony’s wealthiest families were melded. It’s reasonable to speculate that Martha may have been a student at Ellinthorp Hall given her family’s stature and connections with the school. The pattern of Martha’s existence, traceable through those of the men in her life, is a narrow one: married while still in her teens; mother to several children during her marriage; and dead, of tuberculosis, by age thirty-one.

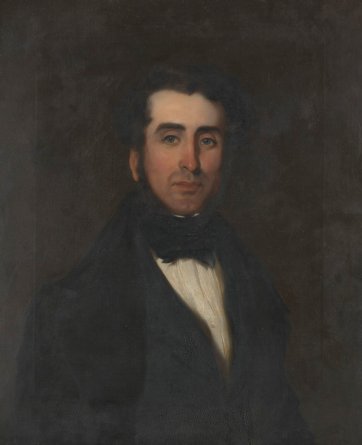

Mundy’s portraits of the couple are prime examples of his practice, unsigned, as were all his canvases, but bearing his signature in their elegance and sensitivity, their seamless handling of paint; and in the expressive, potent rendering of the subjects’ eyes and faces. Less elaborate than Mundy’s paintings of subjects like the Archers and Lawrences, the Kermode portraits demonstrate the understated language of other examples of his work, such as the portrait of his brother-in-law, Francis Aubin, and the portraits of businessman Thomas Harbottle and that of Mary, his fetching, ringleted wife.

But Mundy’s skill as painter was not sufficient insulation against the slump in demand for portraits which hit with the economic depression of the 1840s. Mundy left Launceston in search of work. He moved to the east coast, nearer his wife’s family, and set up business in Hobart where, in 1842 and 1843, he was advertising as a portrait painter and offering lessons in drawing, painting, ‘pianoforte and flute’. His work attracted favourable attention and he was commended for his ‘excellent taste and professional ability’ on the display of two of his portraits in 1844, and for the ‘warm and vigorous’ style with which he executed Harbottle’s likeness, exhibited at RV Hood’s Hobart picture gallery in 1846. By this date, however, he was living some distance from Hobart, at Swanport, where he tried to earn his living by farming – a profession ‘for which he was in no respect suited’. Burdened with what a friend described as these ‘professional disappointments’, Mundy entered the period of personal decline that ended with his insalubrious death at the Ship Hotel.

With the years of Mundy’s activity as a painter in Tasmania amounting to less than a decade, known examples of his work are few in comparison to those of some of his contemporaries. They reside in a selection of galleries and museums or in the collections of families descended from those who commissioned portraits from him. It was from such a collection that Robert and Martha Kermode’s portraits were acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 2008. Originally displayed in the family home – Robert in the entrance hall of the palatial house he built in the 1860s; Martha in the breakfast room – the portraits were passed along four generations of the Kermode family, out of sight of art historians from the time they were painted. The original frames – one attributed to a nineteenth century Tasmanian maker, and the other by a London framer – were separated from the paintings in 1995 and purchased by the National Gallery of Victoria. In keeping with its policy of re-uniting paintings with their original frames, the NGV has made a gift of the recently-conserved frames to the Gallery. Robert and Martha Kermode’s portraits are acquisitions to boast about, a pair of paintings that will both gild and deepen the collection: handsome, rare and finely realised colonial Australian portraits by one of the finest – if most sadly short-lived – exemplars of the artform.