In 2007 the National Portrait Gallery invited Australian artist James Angus to create a major three-dimensional work for the Gallery’s entrance forecourt.

Angus has long been interested in how the visual forms of physics, biology and mathematics inform our perceptions of time, space, scale, mass and movement. The large-scale work titled Geo Face Distributor is a subtle exploration of the representation of the human face with a dynamic and powerful physical presence.

James Angus, born in Perth, Western Australia in 1970, shares his time between Australia and the usa. The first museum exhibition of Angus’s work at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 1992 surprised viewers with its resolute and conceptually rigorous interrogation of spatial dynamics, and its engagement with the processes of industrial production.

In the late 1990s Angus produced a number of sculptural works that represented carefully chosen animals and objects. A life-sized yellow fibreglass rhinoceros, pink rubber giraffe, and painted bronze dodos evoked perceptual complexity and analysed assumptions of scale and form. The very specific nature of the subjects of Angus’s sculptures reflected their rich cultural and semiotic capacities.

In 1999 he made several sculptures of a basketball and soccer ball where the use of computer-assisted design techniques enabled the artist to apply physical forces theoretically in virtual space. A real basketball was scanned in 3d and reproduced inside the computer; a soccer ball was created mathematically using computer design. These simulations were then subjected to theoretical velocity and force, captured at the moment of impact with the earth after being dropped from the cruising altitude of a 747 jet airliner, and reproduced as sculptures cast in plaster and bronze.

Angus’s work continues to be informed by philosophical reflections on architecture and physics as well as the aesthetics of quantum-scale forms and patterns.

Geo Face Distributor is a bold new addition to the Portrait Gallery’s collection and presents a dramatic experience for the Gallery visitor. I think it would be good to start with the basics. What sensations do you wish the work to convey, and what does its title describe?

Well, put simply, I want people to be able to see faces. At first glance, it looks like a slightly monstrous lump of… something. But then the faces emerge: cavities link up to form pairs of eyes and mouths, protrusions start to look like noses. And then they might equally disappear and the whole thing collapses back into something unnameable. So I’m hoping the sculpture will create a pushing and pulling of focus.

The title Geo Face Distributor partly describes this effect but in more prosaic terms. Geo refers to the use of geometry to create the surface of the work. It also implies geography and the topography of the earth. Face is obviously a prompt for the process of figuration, and Distributor refers to the process of mapping those faces onto the sculpture. However it occurred to me that Geo Face Distributor could equally refer to one of the tasks of a portrait gallery.

Could you briefly explain the process of fabricating Geo Face Distributor, the reasons behind your choice of surface colour, and the inspiration for the form of the object?

The project started with a fist-sized lump of clay some time ago. I fooled around with it a bit and came up with a system for distributing regular networks of peaks and depressions across the surface. Then I went to an industrial designer who built a computer model of my lump of clay. We smoothed out all the minor lumps in order to produce a surface made principally of compound curves, and distorted the proportions so it looked more like a human head.

Once we had all the surface data, it was simply a case of choosing a scale and having the patterns milled with a CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machine, which is effectively a robotic sculptor. Then the patterns were taken to a foundry and sand-cast in aluminium, assembled, and painted.

I chose the colour quickly and almost without thinking and I’m still trying to work out exactly why. It’s a slightly dirty orange and I knew this would push the object in an organic direction and work against the more industrial process of sand casting. I thought it might look more like a landscape if it was orange. And given that it announces the entrance to the museum, my instinct was also to choose a colour which would be bright and legible.

I am interested in the relationship – for you – between hand modelling and industrially-aided composition; and between the organic and the mathematic outcome in your work. Is it something instinctive?

Instinctive would be a good way of putting it. I mean, hands are good for thinking with, but I’m also really attracted to the idea of using geometry as a kind of filter.

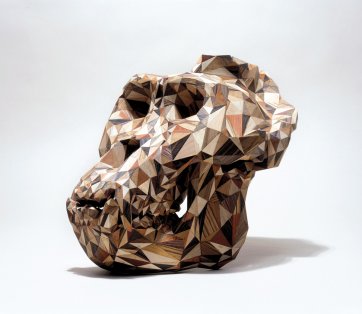

Geo Face Distributor bears a conceptual relationship to some other recent works of yours, particularly the ‘mountains, valleys and caves’ works, and the gorilla skull. How do you see Geo Face Distributor in relation to your other works?

The mountains project is a bit different from other things I’ve been making. It was basically the result of playing around with default settings in 3D modelling software and the shapes are much more arbitrarily determined than anything else I’d made before. I guess the idea of figuration was introduced via the title, but otherwise there’s not much to separate it from formal, abstract sculpture. In some ways, the Geo Face Distributor came out of coaxing a more figurative system out of the same software. The geometry is not so different from the mountains project, except that it’s wrapped around an ellipsoidal template rather than a planar one. So I guess it’s fair to say that it’s really only this simple process of rewrapping that creates a shift from landscape to portrait. Maybe the Geo Face Distributor is similar to other projects in terms of the demands it places on the vision of its audience. There’s very tactile, obvious, topography which is easy enough to apprehend, but it requires a leap of faith and imagination in order to get to the next level.

Could you tell me something about the relationship between abstraction and figuration in the gorilla skull sculpture?

That particular sculpture started with a real gorilla skull, which was digitally scanned. In other words, the surface was very accurately translated into an enormous set of Cartesian coordinates, millions of them. The idea was then to massively reduce the amount of data in order to make the underlying geometry visible - at the expense of the legibility of the thing being described by it. So the surface was eventually articulated by only several thousand points, which were then connected up with pieces of wood veneer. Here, the filter of geometry created an obstruction. When you look at this object, there is supposed to be an underlying threat of camouflage, something disappearing, or something figurative becoming abstract. It’s the opposite of the Geo Face Distributor I think.

The gorilla skull took a figurative, representational starting point (a real gorilla skull) and translated it into a set of coordinates or an equation so that it was re-manifested as an abstract sculpture. Geo Face Distributor began its life as an essentially abstract but malleable physical object (a mass of clay), that was then digitally mapped and manipulated in virtual space, before being realised as a scaled up object that is suggestive of figuration and human representation. James, are there specific works of yours that you see as informing Geo Face Distributor?

Not specific ones. I mean, certainly I’ve been interested in how to represent things for a while. My 1996 sculpture of a life-sized rhinoceros, for example, came out of a similar interest in creating filters for viewing figurative sculpture, with a totally different outcome. In that case the starting point was a realistic sculpture created from close observation of the actual animal in real life; however it was presented in the gallery in a way that transformed the viewer’s perception of it (the fibreglass rhinoceros sculpture was painted bright yellow and mounted horizontally on the gallery wall). But the Geo Face Distributor really evolved from a different line of enquiry. As I mentioned earlier, it came out of trying to understand defaults in computer-aided design software and the formal language of contemporary industrial design. I think an architectural historian might refer to these sculptures as follies.

Maybe I should draw your attention to the sculpture I made immediately before this one, when I was trying to work that particular problem out. It’s called Pareidolic Spheroid, and it’s the first attempt to map those mountain shapes onto an ellipsoidal template. It is much busier to look at and the faces are consequently more grotesque and difficult to see, which led me to simplify the whole thing. Actually, I should have mentioned the word pareidolia earlier. It’s a term that psychologists use to describe the tendency to see recognisable forms in randomly formed patterns and shapes.

We have alluded to a range of disciplines including industrial design, mathematics and psychology. Could you sketch out the terrain of some of your broader research interests?

One concern which I think connects up a lot of my work is an impulse to make sculpture which somehow describes a new set of conditions for objecthood, particularly with regard to what I would reluctantly refer to as digital media – computers, basically. It seems to me that there’s potentially something reactionary in still objects these days. So I’m curious to know what happens when computer-designed surfaces – which are essentially the everyday surfaces of late capitalism – are applied to the formal strategies of a sculptor like British modern artist Henry Moore. Or how USA artist John Chamberlain’s abstract sculpture – assembled from crushed discarded automobile chassis - might be viewed through the lens of applied engineering. These are both artists I’m really interested in, but the trick is to figure out how to create new meaning in the wake of what they’ve done. Or maybe what I’m doing is really just the wagging tail of this same kind of modernism. I guess these are the sorts of questions which keep me up at night.