Like any number of eighteenth-century men of distinction, William Bligh was not shy about having his portrait taken. A naval officer, a colonial governor, a legendary navigator, cartographer, author, a father of six and a dutiful husband: these are all truths which might be discerned from a look at portraits of William Bligh, but which are more than overshadowed by the popular memory of him as the cantankerous casualty of Australia’s only coup d’état and perhaps the best known of all naval mutinies – that of the crew of HMS Bounty in April 1789.

Recently acquired by the National Portrait Gallery, Robert Dodd’s 1790 print of this infamous event began a tradition of images of William Bligh that have served to fix in the memory contradictory portraits of his ‘true’ character.

Born in Plymouth in 1754, William Bligh had lived a colourful life by the time he joined the Bounty. Bligh first went to sea around the age of eight and joined the Royal Navy as a teenager. He spent three years learning navigation and seamanship and was twenty-two when Captain James Cook selected him as Master of the HMS Resolution for what would be Cook’s final voyage of discovery. Bligh spent the years following the return of the Resolution as a Lieutenant, serving on a number of ships before, on Sir Joseph Banks’s recommendation, getting the job of the Bounty’s commander in 1787. This voyage, however, was blighted to begin with. It came about as a result of Banks’s effective lobbying on behalf of British sugar plantation owners, who wanted a vessel to sail to Tahiti and collect breadfruit specimens for transport to the West Indies, where the plants would be cultivated as a food source for slaves. The Admiralty, reluctant to spend money on a voyage that was tainted by association with the slave trade and devoid of any noble military or scientific purpose, cut costs with a too-small vessel, a mediocre crew and by not supplying the customary contingent of Marines to keep order. The usual shape of shipboard hierarchy was also compromised by Bligh’s junior rank and the lack of other commissioned officers on the voyage.

The ship reached Tahiti in October 1788 and during the six months it remained there the crew acquired quite a taste for the local lifestyle. Fabled for its climate, abundance, and willing women, Tahiti presented a heady concoction which melted the harsh codes of discipline in the starkest of contrasts to the stitched up, stickler-for-the-rules that was the Bounty’s commander. The crew traded avidly for ‘curiosities’ like weapons, bark cloth and trinkets, formed relationships, and acquired tattoos as a badge of their infatuation with the island. The comparative ease of Tahiti would have been a welcome relief after the hard conditions at sea under a man known for his foul mouth and brittle temper. By the time the ship left, the already flimsy distinctions of rank had unravelled further, and discipline – always more difficult for captains to maintain on shore – had deteriorated. Three weeks out from Tahiti the crew, following the lead of Fletcher Christian, mutinied. In the logbook he kept of the incident, Bligh related being dragged from his cabin at sunrise, bound, and repeatedly threatened with having his ‘brains blown out’ before being set adrift in the ship’s launch with eighteen supporters. With minimal provisions and no maps, Bligh successfully navigated the seven-metre-long open boat nearly 6000 kilometres to Timor, managing to keep his companions alive and during the voyage charting part of the coast of Australia. The precise cause of the mutiny has been endlessly debated, but in short it seems to have erupted from a very complex mix of personalities and duress. Some have blamed Bligh’s abrasive manner and a rigid insistence on order that hardened the crew against him and lost him their respect. There is suggestion that he was a bully and that Christian – a family friend who had sailed with Bligh on previous voyages – cracked under pressure from criticism and abuse. Bligh himself put the mutiny down to his crew’s inability to resist the temptation to return to ‘the finest Island in the World where they need not labour, and where the allurements of dissipation are more equal to anything that can be conceived’.

The idea of Tahiti as an earthly paradise was well established by the 1780s and owed much to the accounts of earlier Pacific voyages. Naval captains kept detailed journals with documentary intention as well as with a keen sense of the worth of such stories to publishers satisfying the Enlightenment-age appetite for books and images of exotic places. In addition to cataloguing geographical and scientific discoveries, such accounts presented Europeans with their first glimpses of people whose social codes were dramatically ‘other’, especially as they related to women. The journal of the Endeavour voyage kept by artist Sydney Parkinson and published in 1773, described Tahitian women as being ‘bred up to lewdness from their childhood’ and similar narratives did not shy away from references to their beauty or ‘wantonness’. The account of Samuel Wallis, who captained the Dolphin to the Pacific in 1767, related circumstances where sailors purchased sexual favours for mere pieces of iron, creating such a frenzied need for nails that his ship was at risk of being pulled apart, ‘the size of the nail that was demanded for the enjoyment of the lady [being] always in proportion to her charms’. These extracts from Wallis’s account and other ‘secret anecdotes of Otaheitean Females’ were included in a pro-Bligh pamphlet published in 1792. Even by the standards of libertine London or saucy dockside towns, tales of this sort of trade aligned the Pacific in some European minds with a rare level of freedom and temptation. Bligh’s theory about the cause of the mutiny was thus perfectly believable and readily devoured when served up in a society where such subjects were the basis of coffee house conversation. With its subplots of sex and violence, adventure and exoticism, the mutiny story was ripe for plundering from the start.

Bligh made sure that his version of events would be the first to hit home and, with his account of the voyage and mutiny which was published within months of his return in 1790, started what has become a long string of texts seeking to demonstrate the ‘truth’ about the event. Likewise, Robert Dodd’s engraving of the mutiny and other notable portraits of Bligh of this time are potent images that assumed greater significance as unflattering allegations emerged in the wake of the trials of those mutineers the Admiralty managed to round up and the campaigns they mounted in their defence. Dodd, a prolific artist of maritime subjects, was among a number of printmakers who exploited the market for images of famous ships and battle scenes. Dodd’s images gratified the chest-thumping feelings inspired by military actions and were characterised by a heightened sense of drama and bombast, making liberal use of flames, cannon fire and storm clouds. Such narrative devices were typical of those employed in the prints of the era, designed to tell a story, often to a lettered readership. Bligh is said to have approved of the original image and advised Dodd on some of the likenesses. In its detail, the work corresponds with eyewitness accounts, showing Bligh and his supporters having cutlasses thrown to them just before being cast adrift. Bligh is delineated by sunlight and cast in heroic mode and Christian, described in heated moments by Bligh as a ‘diabolical looking’ man with a ‘tattooed backside’, is depicted standing on the stern of the ship surrounded by jeering mutineers and the breadfruit trees which they later threw overboard.

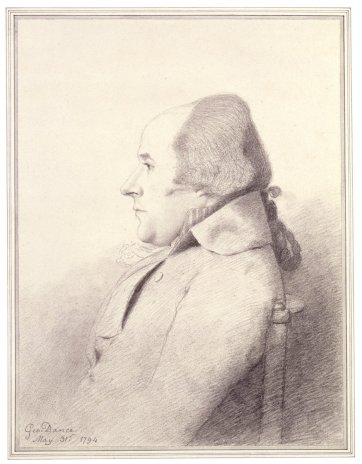

The title of John Russell’s 1791 portrait endows Bligh with the rank of Admiral (something he didn’t achieve until 1814) but was painted at the time that he made Captain, just before he sailed for Tahiti again to finish the job the Bounty had neglected to accomplish a few years earlier. It’s an image which marks Bligh’s promotion and signifies his status as a gentleman with his elaborate uniform and powdered wig, depicting a dignified and composed man with not a hint of the profane, hot-headed seaman that he also was. Depicted in the background is what some experts believe is the launch in which Bligh made his extraordinary journey to Timor, and Russell’s painting was the basis for an engraving which appeared as the frontispiece to Bligh’s Voyage to the South Seas, published in 1792. George Dance’s pencil drawing of Bligh is among a series he made of friends and contemporaries including James Boswell and Charles Burney in the 1790s. The inclusion of Bligh in this series indicates his place within the educated or intellectual classes and presents what is believed to be a close, unadorned and honest likeness of Bligh in respectable middle age.

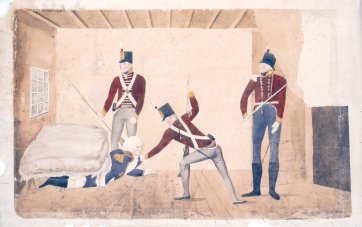

Yet despite his general integrity and his status as a heroic survivor, Bligh’s reputation for tyrannical behaviour continued to mar his career, most notably when, as Governor of New South Wales, his clashes with equally belligerent colonists ended in his forceful removal from office in January 1808. Unfortunately for Bligh, the only contemporary image of this second mutiny against him is a blatant piece of propaganda that has successfully fixed an image of him as cowardly and petulant. The watercolour by an unknown artist – reproduced and issued as a lithograph later in the nineteenth century – misleadingly shows Bligh being dragged out from a hiding place under a bed. Crude in execution and intention, the image owes its language to the virile and irreverent culture of caricature in Georgian times, when politics or the private lives of the elite were something of a sport and events such as the overthrow of a governor might be celebrated with pub signs and effigies.

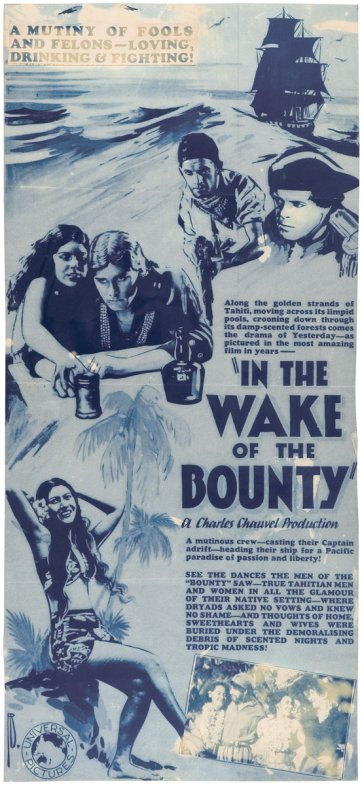

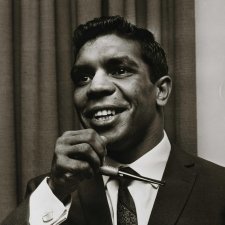

Even after Bligh died in 1817 – ‘loved, lamented and respected’ according to his epitaph – the controversy about the mutiny and his character continued with the publication of poems, articles and memoirs which either defended or vilified him. In the twentieth century, the mutiny was made the subject of five feature films, some of which have earned their own notoriety for their fast and loose style of playing with history. Raymond Longford’s 1916 Mutiny of the Bounty, the first of two Australian films on the subject, was advertised as a story of ‘brutal tyranny and oppression, of violent passion, of murderous revenge’, locating the cause of the mutiny in the ‘repulsive defects’ which overshadowed Bligh’s otherwise admirable characteristics. Charles Chauvel’s In the wake of the Bounty, released in 1933, presented the mutineers as ‘madmen bewitched by Tahiti’s soft guile’. While somewhat more nuanced in its exploration of the mutiny, in playing with its undercurrents of lust and exoticism In the wake of the Bounty set some of the less ambivalent standards observed by subsequent film versions of the story. In his first lead role on film, Errol Flynn was cast as a suave Fletcher Christian and Chauvel’s film scandalised Customs authorities who initially declared its footage of topless, grass-skirted Tahitian women too lewd for distribution. In a similar vein, posters for the 1935 Hollywoodattempt, Mutiny on the Bounty, advertised ‘Maidens!’ and ‘South Sea Love!’ as prime ingredients. This film and its 1962 remake are partly remembered for legendary off-screen events as well as for their scant attention to accuracy, with Bligh cast as relentlessly cruel and Christian as a charming romantic and a tragic hero. These characterisations were exemplified in the casting of older, redoubtable British actors in the role of Bligh against some of film’s greatest poster boys as Christian: Clark Gable in 1935, Marlon Brando in 1962, and Mel Gibson in the 1984 film The Bounty. Seizing on the same elements that had made the Bounty narrative so juicy in Bligh’s lifetime, filmmakers have further imprinted the myths that make the ‘real’ William Bligh almost impossible to extract from two centuries’ worth of vivid re-tellings of an always intriguing story.