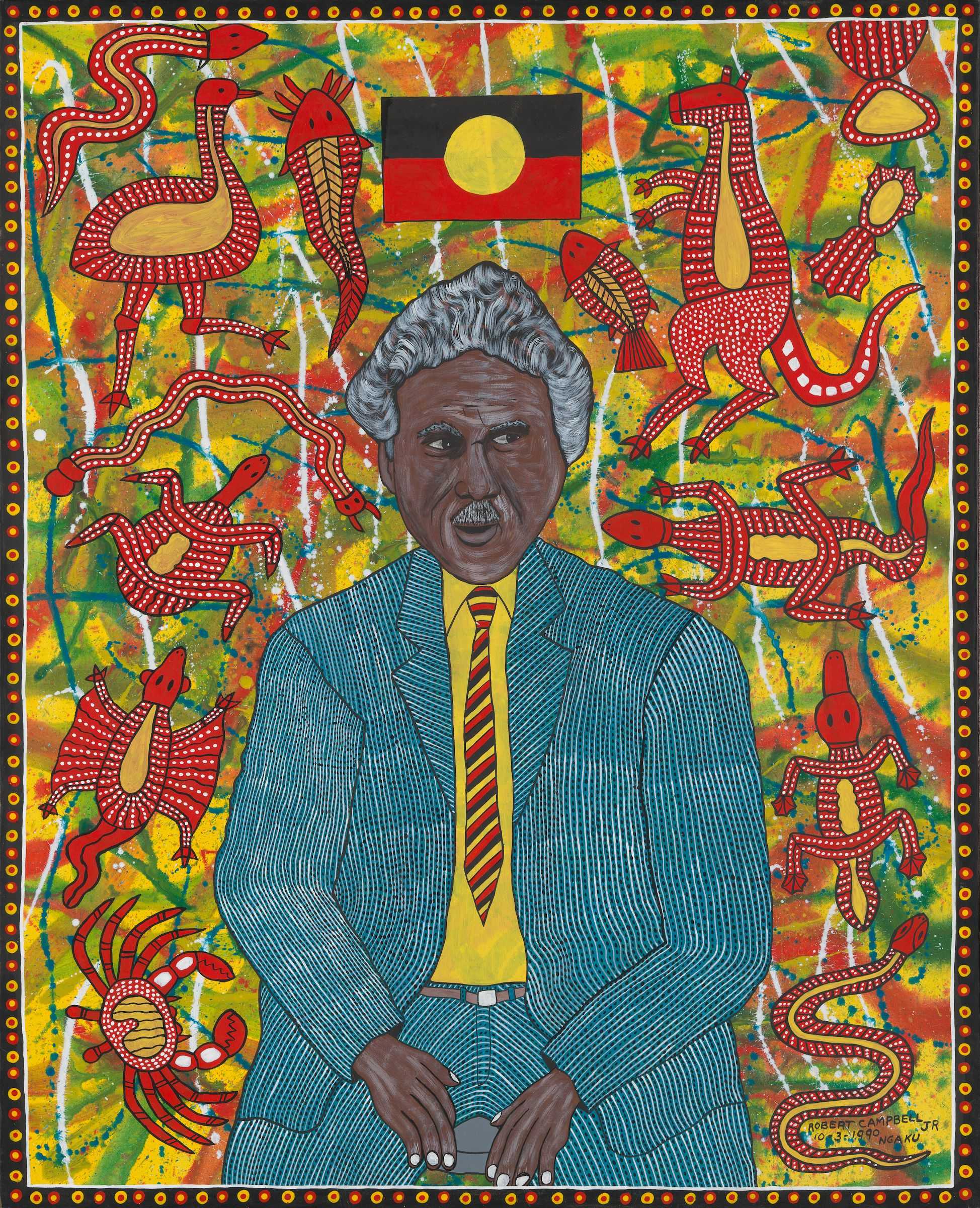

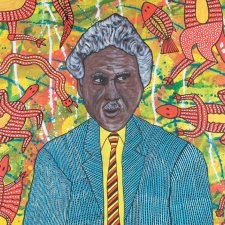

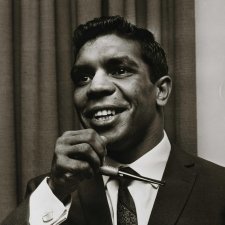

Who would have the sartorial confidence or political courage to wear a red, yellow and black tie? Who indeed, but an Indigenous Australian leader.

In his portrait of Senator Neville Bonner, Robert Campbell Jnr (1944–1993) makes sure we know the where his subject’s allegiances lie. Bonner is wearing the colours associated with Aboriginal Australia. The Indigenous tricolour in Bonner’s tie is not traditional; it was introduced in the early 1970s as the Aboriginal flag with its black and red bands and yellow central disc.

This flag (and there were others before it) was designed by Indigenous elder and member of the Arrernte (Aranda) tribe of Central Australia, Harold Thomas in 1971 and first flown in Adelaide on National Aborigines Day the same year. But it was when the flag was flown over the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in Canberra in 1972 that the red, black and yellow design took on national significance. According to Thomas, the flag symbolises Aboriginal identity: the red represents the red earth and the red ochre used in Indigenous ceremonies; the yellow disc represents the sun as giver of life and yellow ochre to reinforce the association of the earth with its people; and the black represents all Aboriginal Australians. By the time Cathy Freeman draped herself in the flag for a lap of honour at the Commonwealth Games in 1994, it had become the de facto standard for Indigenous Australia. The Aboriginal flag was officially recognised under Federal legislation in July 1995.

Robert Campbell Jnr commemorated the establishment of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in front of Parliament House in Canberra in a painting of 1986. The Tent Embassy, which appeared on the lawns of Parliament House in the afternoon of Australia Day in 1972, drew attention to the frustration of a people who were denied land rights and who felt that they were treated like foreigners in their own country. In a sequence of comic strip-like panels, the artist shows the initial small group of activists and Indigenous leaders gathered around the Embassy, while the second panel shows the violent confrontation with police and the subsequent arrests. Campbell’s painting is highly decorative and schematic. He cares little for the conventions of perspective and his art’s naive appearance belies the sophistication of the concept and the complexity of the composition. To the figures and landscape alike (even the blue paddy wagon) he applied an overall patterning of lines and dots, taken loosely from the traditional decoration of shields made in North Eastern Australian and the Kempsey area where he was born. Campbell’s father was a boomerang maker and Campbell grown up with the example of painted and inscribed designs on carved wood. He drew birds and animals on the boomerangs and his father would burn the designs into the wood with a hot wire. Campbell retained this emphasis on line in his mature work. There was little interest in Indigenous art in the Kempsey region during the 1950s and it was unlikely Campbell would develop as a traditional painter. Indeed, the local traditions had all but been lost and what remained was geared to craft production for tourist trade. Instead Campbell invented his idiosyncratic highly illustrative style with a strong emphasis on outline and pattern, using acrylic paint in bright colours which he applied to figures and landscape with an enjoyment that speaks directly to the viewer.

Campbell’s choice of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy as a subject was not a one-off: he was fascinated by history and painted stories from his youth as well as contemporary events. He painted, for example, Azaria and Winning the America’s Cup in 1989 and Gas fire explosion at St Peters’ in 1990. Most of his work has strong political connotations prompted by the injustices he saw around him. The titles of his paintings make this clear: Deaths in custody; Roped off at the picture show; Barred from the baths; First sighting of the Whiteman; Robert Marbuk Tutawallie Supports Aboriginal Stockmen Striking for Equal Pay at Wattie Creek. The last painting shows the Robert Tudawali, the star of the 1955 film Jedda who, as Vice President of the Northern Territory Council for Aboriginal Rights, actively supported the stockmen who walked off the Wave Hill cattle station in 1966.

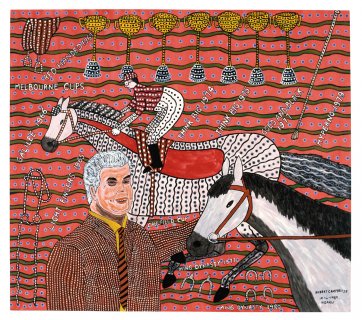

Campbell depicted his heroes with the same enthusiasm. He painted a number of striking portraits of leaders and sportsmen including horse trainer Bart Cummings, boxer Jeff Fenech, activist Charles Perkins, singer Slim Dusty, a number of self portraits and politician Neville Bonner. His portraits are illuminated with attributes that offer us some idea of the person we are looking at. Bart Cummings is shown with his string of Melbourne Cup winners and several Cups for good measure. Fenech is shown as a champion boxer but smaller illustrations show his rise from a life of crime and trouble with the law to finally making good. It is interesting to see that he is depicted with a darker skin that is nowhere as white as that of the police man. The emu tracks scattered across the background of the painting lets us know this man is fast: he can twist, turn, and is fleet and agile on his feet like an emu. Charles Perkins is shown microphone in hand, addressing a land rights rally. Behind him is an idyllic and idealised Australian background, a reminder of the bygone golden age lost when the Europeans colonised Australian and a portent of what was to come when leaders like Perkins would lead the Indigenous people from the wilderness to reclaim land and dignity. He wears the Aboriginal flag across his heart.

On first sight, the people in Campbell’s paintings appear to be ready for a formal occasion, each seemingly wearing a red tie. Notably, so are all the creatures, birds, animals and fish, that appear in his paintings. This red shape owes more to Arnhem Land X-ray painting – which makes the internal organs and bone structures visible – than to fashion. Borrowing from the bark paintings of Northern Australia, Campbell gives a red tie-like oesophagus shape to all living beings in his work to symbolise the powerful life force and essential animal nature. And Neville Bonner? Well he is exceptional in Campbell’s oeuvre for actually wearing this impressive striped tie, one of many potent political symbols of Aboriginal identity in this portrait.

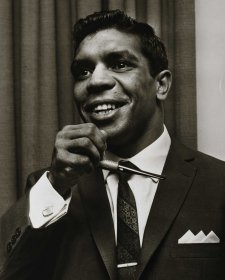

Senator Nevill Bonner AO (1922–1999) was the first Indigenous Australian to serve in the Federal Parliament. He was born on Ukerebagh Island, Tweed Heads to a Jagera woman and an Englishman. Brought up by his grandparents he had little education and lead a life of hard work until the referendum of 1967. He then determined the need for change and joined the One People of Australia League, becoming Queensland president from 1967 then national president from 1980. Bonner, a member of the Liberal Party since 1967, was asked to fill a casual vacancy in the senate in 1971 (the same year that Harold Thomas’s Aboriginal flag was designed) and was then elected in his own right in 1972, the year the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was established. He served until 1983 when he left the Liberal Party and Federal politics. Bonner was named Australian of the year in 1979 and was appointed an officer of the Order of Australia in 1984. Campbell’s portrait acknowledges Bonner as a prominent Aboriginal man and attempts to record his iconic status within Indigenous society. Campbell portrays Bonner at the height of his power, when the excitement and potential for change crackled in Australian life and politics.

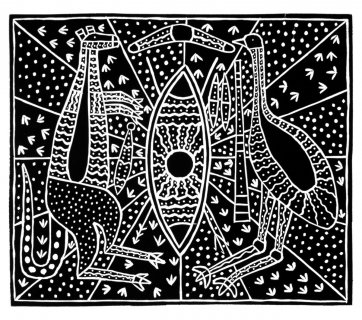

Campbellcelebrates Bonner’s association with the Federal Government by placing his own version of the national crest above his subject’s head with the armorial kangaroo and emu flanking the Harold Thomas flag. A linocut of 1986, Aboriginal Emblem, also shows Campbell’s version of an Australian coat of arms readjusted to accommodate an Indigenous perspective: a traditional shield blazoned with a radiant sun sits between the ubiquitous kangaroo and emu guardians. This sly attempt at formality is Campbell’s way of indicating that he wants viewers to be aware that they are looking at a statesman. These two ennobled indigenes, the kangaroo and the emu, are part of a varied but dinki-di menagerie that form a field behind Bonner. The animals – as with the horses and cups in the portrait of Bart Cummings or the emu tracks behind Fenech, extend our understanding of the sitter’s story. The kangaroo and the emu are emblematic of Australia and its people. Likewise particular animals are associated with different groups of Indigenous people as totems. The Australian creatures in the painting may represent all native Australian clans and equally Bonner’s kinship with all groups. Campbell also includes the image of shellfish and crab, a reference perhaps to the river mouth where Bonner’s own mob, the Jagera people, live.

Robert Campbell Jnr’s career emerged in the mid eighties just as Bonner was retiring from Parliament. It is unlikely that Campbell met Bonner while he held office but probable that he did soon after, when they both had achieved recognition in the community. However, there is little to indicate that this portrait was painted from life. It was Campbell’s practice to work from newspaper photographs for his portraits. The charm of his works is that he portrays things not as they are seen or observed but as they are known and understood.