Harold Cazneaux's portraits of influential Sydneysiders for the style-bibles of the day eschewed the romantic for the naturalistic.

In his forty-year career as a photographer, Harold Cazneaux created a rich catalogue of Sydney’s mood and people. Cazneaux’s iconic cityscapes and street scenes have come to define the Sydney of his time and his many portraits offer a glimpse into the small social world which linked the city’s primary tastemakers in the 1920s and 1930s.

Two such portraits by Cazneaux have recently been gifted to the National Portrait Gallery – one of artist Margaret Preston, taken in 1930, and the second of author Ethel Turner, photographed in 1928. Bestselling author Ethel Turner (1870-1958) was prominent in Sydney’s literary and social circles from the 1890s onwards, while Margaret Preston (1875-1963) enjoyed an enviable place in the Sydney art establishment and a reputation as one of the city’s foremost modernist artists. Both women can be considered important figures in the development of ideas about Australian identity and culture which emerged in the first half of the twentieth century.

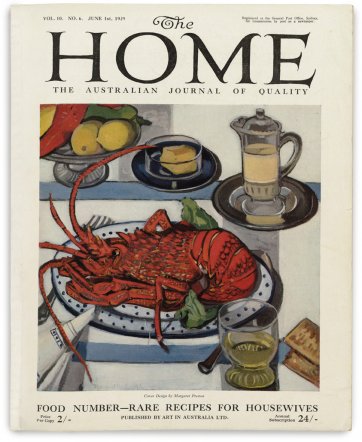

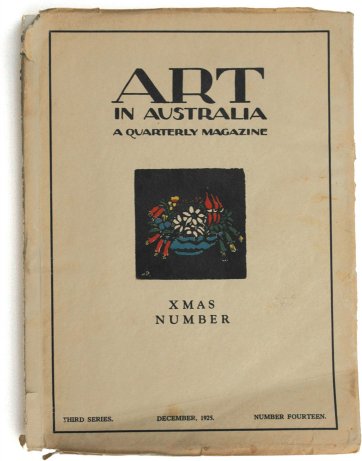

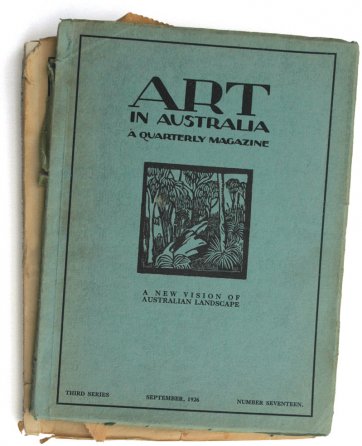

Harold Cazneaux (1878-1953) arrived in Sydney in 1904 and worked for the commercial studio Freeman & Co. while with his own work established a strong profile in photographic circles for images of the city’s streets, people and daily life. He was a founding member in 1916 of the Sydney Camera Circle, a group which endorsed photography as an art form akin to painting, and which also promoted the development of a form of pictorial photography with a distinctly Australian character through use of local qualities of sunlight and shadow. By 1920, Cazneaux had set up his own studio at his home at Roseville, and was engaged by influential publisher and artist Sydney Ure Smith as the official photographer for Smith’s stable of style-bible magazines which included The Home and Art in Australia. The work for Smith called for a diverse output, including numerous portraits of Sydney identities and their lifestyles. While he later admitted that photographs of Sydney socialites were his most disliked assignments, Cazneaux enjoyed photographing members of the creative circles he moved in. Artists like Norman Lindsay, Rayner Hoff, and Thea Proctor were photographed by Cazneaux, as were others within the cluster of arbiters of art and style who enjoyed Ure Smith’s regular patronage.

Margaret Preston moved to the harbourside suburb of Mosman in 1920 and throughout the next two decades created many of the exuberant works which remain among the most popular and recognisable in Australian art. Preston drew powerful inspiration from her extensive travels and the bushland around her home and became a vigorous campaigner for her vision of a modern Australian art that recognised Indigenous art traditions and the unique beauty of native flora and motifs. Preston was adept at promoting herself and her ideas, regularly contributing cover designs and illustrations for The Home and Art in Australia as well as articles for these and other publications. The 1920s and 30s were a prolific and diverse period of output for Preston. She experimented with techniques, working in painting, printmaking, craft and design, to create a modern visual language which melded Aboriginal form with modern art’s bright colours and bold structural qualities. Her woodblock prints and paintings of this era are celebrated for their Australian subjects, such as wildflowers, harbour scenes, and images of Sydney’s growth as a modern metropolis.

Similarly, Ethel Turner’s work is remembered for its celebration of unashamedly Australian themes. Turner came to Sydney with her family at the age of nine and was twenty-four when her first and best-known book, Seven Little Australians, was published in 1894. The novel was a blistering success, the first edition selling out within weeks and Turner’s publisher immediately contracting her to produce a sequel, The Family at Misrule, which appeared in 1895. While Seven Little Australians displayed traits typical of children’s fiction of the time – boarding schools, an autocratic father figure, scarlet fever, and the premature death of its rebellious heroine – it was distinct for its Sydney suburban setting and its representation of typical Australian childhood experiences. The rabidly nationalist Bulletin considered Turner among those writers whose work would come to form an Australian literary tradition – an association that caused unease with her English publisher, who sometimes feared her writing was too ‘larrikin’. Like Preston, Turner achieved a prolific output: from 1896 until 1928, she produced an average of one book per year, contributed regularly to magazines, and wrote poetry, plays, a travel book and prose, much of her work retaining the local flavour that had made her first novel so popular.

By the 1920s, both women were ripe for profiling in the publications which were a primary vehicle for dispersing information about modern lifestyles and ideas, and it followed that Cazneaux would create the images that underlined their status within Sydney’s interconnected cultural community. Like many of his portraits, these images demonstrate Cazneaux’s move away from many of the conventions of portraiture of this era. He replaced the overly romanticised or clichéd studio settings with naturalistic poses, advertising his belief that the ‘charm of successful portraiture’ was best achieved through photographing in the ‘natural surroundings of your home and garden’. His portraits of Preston and Turner exemplify this approach as well as signifying the stimulation both subjects found in gardens and landscapes. In this, they display parallels with Cazneaux’s own love of the outdoors and the portraits he created – particularly of his children – in the garden of his home. Cazneaux’s portrait of Ethel Turner shows her posing in the window of her study at her Mosman home, ‘Avenel’, and was featured in an article about Turner published in Australian Home Beautiful in 1928. Cazneaux shared a connection with Turner through her daughter, Jean Curlewis, a writer who collaborated with Cazneaux on publications like Sydneysurfing, published by Art in Australia in 1929. The portrait of Preston is among a series of images made in the same sitting in her garden at Mosman in 1930. In 1936, Cazneaux photographed Preston in the garden of her subsequent Sydney home in Berowra, alongside the Banksia tree which she cited as an enduring source of inspiration. The accompanying article on ‘Margaret Preston at Home’ was published, also in Australian Home Beautiful, in February 1937. Both portraits can be seen as emblematic of the energetic and confident literary and artistic scene of Sydney in the 1920s and Harold Cazneaux’s role as the key documenter of its close-knit protagonists.