I had already been marked by the wars in Africa, but this one really moved me – both politically and personally. As a photographer I felt I could present a visual voice to the suffering and dignity of a nation drowning in the depths of human conflict. The world was not interested in the suffering of Afghans, so I focused on changing this a little bit at a time.

Over the past fifteen years I’ve returned to Afghanistan regularly to document the story of the people and how they cope with war. It has been a very long and often dangerous road full of sadness and devastation, but a journey of mystery and learning too. Getting to know Afghanistan helped me get to know myself. This personal body of work of photographs and diaries will soon become a series of books that may offer a small window into the history and imagination of this beautiful land I’ve been honored to witness.

In March 2006 I was in Kabul at the end of a very exhausting trip shooting a documentary film about heroin addiction. I brought with me ten packs of Polaroid, my Polaroid land camera and various bits I would need to process and archive the negatives. During my six weeks in Kabul I struggled to find the right project to photograph, which may have had something to do with hanging out with heroin addicts and mental patients for a month.

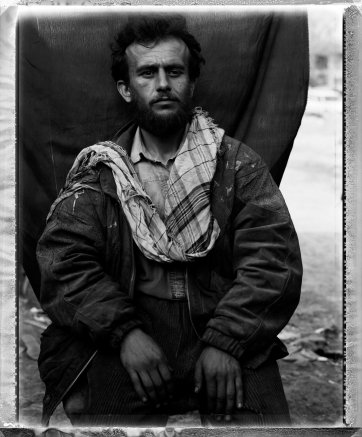

‘Axe Me Biggie’ – a crude Anglo phonetic rendering of the Dari for ‘Mister, take my picture!’ – was my answer to the plea I had heard all over town in the previous weeks. It seems to mean something in English: ‘axe’ being just a more visceral and violent version of the camera verb ‘to shoot’, returning all its original aura of surrender. And because I have this Aussie-rules rugby body, ‘Axe Me Biggie’ also seems a request addressed to me personally. I am Biggie. And on this day Biggie finally answered them all, en masse, saying, ‘Yes, alright. I will axe you, shoot you, take your bloody picture. Have a seat!’

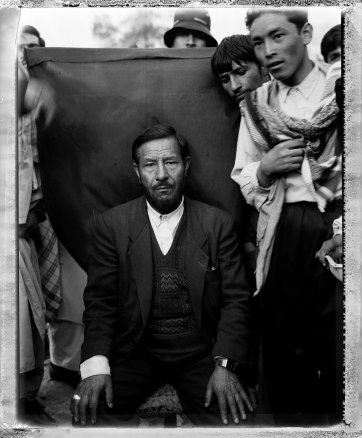

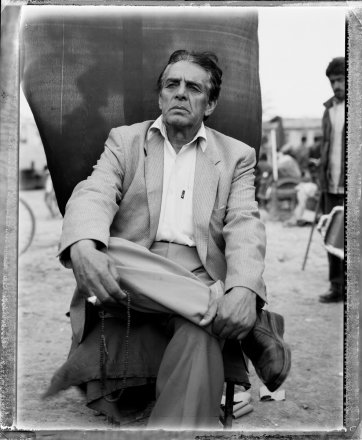

On my last day in town I literally threw myself at the mercy of the streets. I took my camera, bucket of sodium sulphate solution and magic Polaroid’s to the central bus station where the local outdoor studio photographers were located. I borrowed a photographer’s backdrop and set up alongside them. Within minutes there was absolute chaos with over a hundred pushing and shouting men and children all trying to have their portrait done.

It was only when I photographed some police officers with their menacing ak-47s, that a little crowd control came into effect. Things got so bad at one stage that the Chief of Police came down from his office ( the police HQ was directly across the street ) to shout at me and my companions to pack up and move along.

He told us the crowds we were pulling in would attract suicide bombers, so we kept the session on the move dragging along with us the hundreds of spectators. For three hours that afternoon I shot one hundred polaroids, one for each subject, in the most inhospitable manic conditions imaginable. I chose my subjects and shot them very quickly, one after the other. At first I was trying to keep the crowds back and out of frame, but when I gave up I saw something amazing taking shape. What was happening behind the scenes was incredible and the photographs seemed so much more alive and surprising by leaving the crowds in.

I think my portraits illustrate a complex situation that defies easy answers. By seeing the people for who they are my photography might just arouse some sympathy and caution. By exposing the individual suffering and compassion of these people I hope to open up a window into not just their lives, but the lives of others.

This body of work became more than a photography experiment, it evolved into a project that felt real. It was spontaneous and fun and honest. For so many years I have been capturing the ugliness of war and its effects on the people of Afghanistan. I felt like I was giving something back to the people, and I don’t just mean a Polaroid either, I felt that I was giving them all a sense of dignity and pride and hope maybe. This is what I see now in the faces staring back at me, a human experience, a moment in time, the subject and the photographer – a mutual trust and acceptance, a collaboration, a little bit of History.