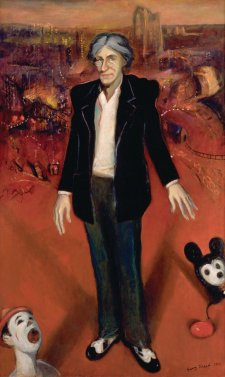

A blasted streetscape dramatises the responsibilities of a man on a mission.

General Peter Cosgrove AC MC (b. 1947), is a former Chief of the Australian Defence Force. Having grown up in Sydney and trained at the Royal Military College, Duntroon, Cosgrove commanded a platoon in Vietnam in 1969-1970, receiving the Military Cross for leading his men in an assault on enemy positions. Over the 1980s and 1990s he ascended through various military roles, commanding the Brisbane-based 6th Brigade, teaching at the British Army Staff College and serving as Commandant of the Australian Defence Warfare Centre before becoming Commandant of Duntroon.

In 1999 Cosgrove was appointed Commander of INTERFET, the international peace-keeping force for East Timor. In the weeks following a popular referendum in August that year, at which a great majority of voters had opted for independence from Indonesia, anti-independence militias had ravaged the country, killing and exiling its citizens and laying waste to its landscape and infrastructure. The Australian-led force was charged with restoring order to the streets and beginning to rebuild the houses, schools, electrical and water supply systems that had been destroyed. Returning from that exemplarily successful mission in 2000, Cosgrove was made a Companion of the Order of Australia and was named Chief of Army. As East Timor continued to progress toward independent statehood, Cosgrove was named Australian of the Year for 2001. In 2002 he was appointed Chief of the Australian Defence Force; he retired in 2005. Last year, just after he had passed the manuscript of his autobiography, My Story, to his editors, he accepted an invitation to lead the Queensland government taskforce rebuilding North Queensland communities affected by Cyclone Larry.

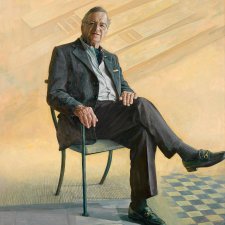

Rick Amor travelled to East Timor as Australia’s first official war artist since Vietnam. In this 2006 portrait, various source images from the period have been reconstructed into an alien and oppressive landscape which converges upon Cosgrove. He stands at the front of a ‘stage’, striding towards the audience, while his soldiers – including his bodyguard, Corporal Kirsty Heam – occupy aloof, yet alert, secondary stances. The ruins surrounding Cosgrove collectively form a theatrical ‘set’, reiterating destruction and abandonment, which contrasts with Cosgrove’s expression of contemplative decision-making and concern. The two figures far in the background are, in fact, Amor and his East Timor guide, Private Cameron Simpson of the Army History Unit.

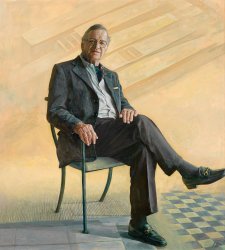

Amor has hinged the complex narrative of this humanitarian crisis upon a single person, a lead actor. Historically, adapting the landscape into an extension of a human subject is not an unusual device in portraiture. Two examples within the National Portrait Gallery collection include Lew Hoad by Ern McQuillan, in which the gaze of thousands of spectators generates a sense of anticipation and pressure, and Tom Uren by Ralph Heimans, where a thunderous sky symbolically links to a pair of discarded boxing gloves and the intense body language of a heated debate. Amor’s use of emotive landscape in this military portrait builds upon an intriguing conceptual perspective for our collection.