Marcus Aurelius questions the idea of fame and the endurance of memory with a melancholic aphorism that is at the heart of what a portrait gallery does - Who is remembered? Who is significant?

Recently a colleague asked about the portrait of disgraced businessman Alan Bond by Melbourne photographer Rennie Ellis: ‘Should this be in the collection? You know he went to jail for misappropriating funds’. The perception was that the doors of the National Portrait Gallery were only open to good people. This observation might be a legacy of the early idealism associated with the foundation of the original National Portrait Gallery in London in 1856. The Victorian era, when the Portrait Gallery opened, bred an aspirational morality that revered hard work, achievement and virtuous deeds. The Portrait Gallery was intended as an educational institution to evoke and reinforce positive values that were epitomized by the teachings of men such as the Rugby School headmaster Thomas Arnold. Aligned with a highly principled and strict ethical code, Arnold introduced mathematics, modern history and modern languages and revitalised the classics in Rugby to benefit the creation of the new industrial society.

When Thomas Arnold’s generation formulated their ideals at the start of the Victorian period, it was evident that a new class and a new age were emerging. No longer did the aristocracy and military alone make history in what was now a truly bourgeois society supported by a strong industrial base. It was evident that the national wellbeing depended on a new class of achievers proficient in science, engineering, medicine, administration and social reform, and resting on an appreciation of the writers, artists and thinkers who also assisted in transforming and regulating this new culture. The Portrait Gallery in London set out to encourage a new civil order vastly different from that of the past and was set up both as a shrine of national pride and to remind Britons of how the nation had been built on individual achievement. It is likely that much of these lofty principles influenced the nascent philosophy underlying its younger sister, the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra. There may well have been a determination to create a gallery that represented only the virtuous, the clever, the socially adept and ambitious – a high-walled enclave of purity and virtue that would exclude rude sinners such as Bondie. But of course this was Australia, a country born with a convict stain, and by 1998 when National Portrait Gallery Canberra opened its doors, it was too late. There was already a snake or three in the garden.

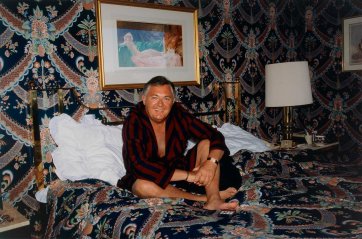

The first display in the new Gallery included the death mask of that notorious Australian criminal Ned Kelly, on loan from a private collection. Kelly is still one of the best-known and perhaps popular Australians. His status as a mythic antihero provides a guide to the tensions in the national ethos of the 1880s and a key to understanding the Australian character. One could argue that Alan Bond had also wormed his way in to Australian hearts with his brash manners, his overt ambitions in business and culture, and his dinkydi, unabashed hunt for a sporting trophy that forever linked the Boxing Kangaroo with the America’s Cup. It would certainly be difficult to envisage Australia in the 1980s without Alan Bond, who was Australian of the Year for 1978. When Ellis’s photo of an affluent, silk kimono-clad Bond is hung side by side with a remarkable loan, a self portrait that Bond painted in gaol, there is the potential to tell a more complex story, a morality play in two acts that tells of hard work and greed, disgrace and perhaps even redemption. In that sense, there is a parallel with the social experiment of the First Fleet with the implication for societal repatriation.

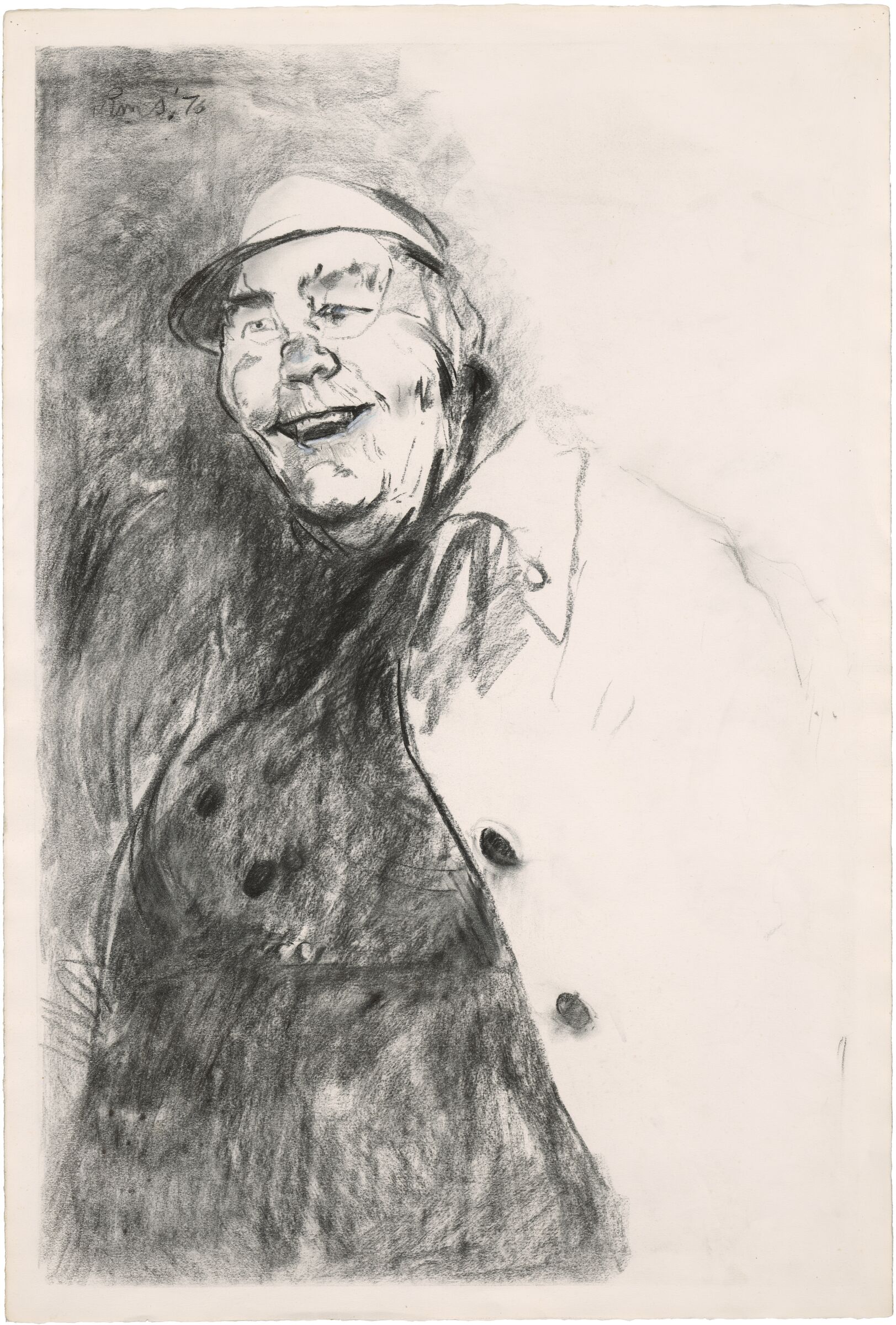

There are other portraits in the collection that depict sitters with a dubious past. Mortimer Lewis, colonial surveyor and architect, was charged with misappropriating materials intended for the new Australian Museum. The Tichbourne Claimant was a much more conventional fraudster: a Wagga Wagga butcher posing as the ‘lost’ heir to a British title and estate in the 1860s. Not that antisocial behaviour is a thing of the past - the collection holds portraits of living Australians such as Mel Gibson and Russell Crowe, both of whose personas are as connected in the public mind with moments of bad behaviour as with acting talent. Sir Eugene Goossens, world-famous conductor is also, tragically, remembered for his sensational arrest for bringing banned material into the country as much as for his quality as a musician. Goossens was infatuated with the ‘Witch of Kings Cross’, Rosaleen Norton (also represented in the collection), and her brand of sexually charged wicca. Norton herself was not a criminal but was certainly an eccentric character.

The Portrait Gallery’s collection holds a number of other, equally colourful eccentrics such as Vali Myers, artist of the occult and living canvas for tribal tattoos, and Bee Miles, a woman with a love of Shakespeare and taxi rides, but a determination never to pay for the latter. We don’t expect our Aussie sports stars to be angels and two new acquisitions made by the photographer Toni Wilkinson don’t disappoint. Weightlifter Caroline Pileggi refused her drug test and was excluded form the Athens Olympics. Olympic rower, Sally Robbins (or ‘Lay Down Sally’ as the popular press named her) appeared to quit mid-race, much to the irritation of her team mates. Not being a good sport sometimes is cricket, at least as far as fame and notoriety is concerned.

All of these individuals are represented in the collection - the good the bad and the ugly. Some, like Crowe and Gibson, were collected before their public disgrace. Clearly, it would be sensible seek subjects for the collection only after they are safely dead and history can judge their achievements in their entirety. Until the 1970s the National Portrait Gallery London would only acquire portraits of sitters after their death, but this stipulation was dropped in the 1970s when it was perceived that the Gallery’s display faced a loss of relevance and connection with contemporary audiences. In the information-flooded culture that we inhabit today, we ‘lose’ history to a barrage of current facts. Fame now seems to last for only 15 minutes, just as the American artist Andy Warhol predicted. Nor is it easy to distinguish between fame and notoriety.

Outside the museum, other media comment on our culture and highlight the activities of imperfect and selfish individuals. Journals, film and television regularly cover the excesses of society and often dwell on sensational crime, antisocial and eccentric acts. Should the National Portrait Gallery likewise record more than the high achievers and the exemplary lives? Other portrait galleries already include criminals: Americans represented in the National Portrait Gallery, Washington, include President Lincoln’s assassin John Wilkes Booth, bank robber Clyde Barrow, gangster, murderer and tax evader Al Capone, Manson family member Lynette (Squeaky) Fromme, and disgraced officer and Viet Nam vet, William Calley Jr. The National Portrait Gallery, London, includes portraits of Guy Fawkes, traitor and mastermind of the gunpowder plot, a host of poisoners, regicides, streetwalkers and thieves and highwaymen from history as well as contemporary villains such as Charles and Reggie, the notorious Kray brothers and the moonlighting art historian Anthony Blunt.

This is not to say the Gallery in Canberra should favour criminals or devote a section of the display space to horror as if it were Madam Tussauds wax museum. Contemporary violence retains a powerful destabilising effect. The image of Moors Murderer Myra Hindley provoked strident and violent protests by relatives of her victims during the Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy in London in 1997. An image of Ivan Milat, the backpacker murderer, would equally raise public ire. The wounds caused by such terrible crimes take time to heal and the inclusion of contemporary murderers who still inspire fear and loathing in the display must affront the public. The Portrait Gallery is conscious of its responsibility. Its Director, Andrew Sayers, has said that ‘Generally we do not want to court outrage or confuse what a portrait gallery is about by committing outrageous acts. There is a strong sense in which in a National Portrait Gallery, inclusion is still considered an honour.’

The portrait gallery is a collection of individual portraits that together comprise a bigger picture – a rich tapestry of interconnected individuals that creates a complex composite portrait of the Australian people, its national character and psyche. Portraits good, bad and ugly, eclectic as they are – and perhaps because of that eclecticism – form a looking glass (not a magnifying glass) to reflect the realities of Australian genius from our contemporary perspective. The references in the National Portrait Gallery display to horse thief and murderer Ned Kelly, colonial embezzlers, prima donnas, unsportsmanlike sports starts and other failed human beings paints a unique portrait of Australian society, more complex and realistic than it would be without their inclusion. As Charles Dickens noted in Pickwick Papers, ‘There are dark shadows on the earth, but its lights are stronger in the contrast.’