Cameron took more than twelve hundred photographs over the course of her career. The portrait of Eyre is one of the 275 individual male portraits that make up nearly a quarter of her known work.

These are distinct from portraits of women, her largest subject group (more than 400) and smaller groups of religious studies, photographs of children, illustrative narratives, and the last, relatively small, group of pictures taken before her death, when she and her husband Charles joined their sons in Ceylon on their family plantations. The portrait of Eyre can be located in relation to an ongoing series of singular portrait studies commenced after Cameron purchased a camera that held 11" x 15" glass plates in 1867. This series was later coined 'Famous Men and Fair Women' by Cameron's great niece, Virginia Woolf, the daughter of her favourite subject Julia Jackson.

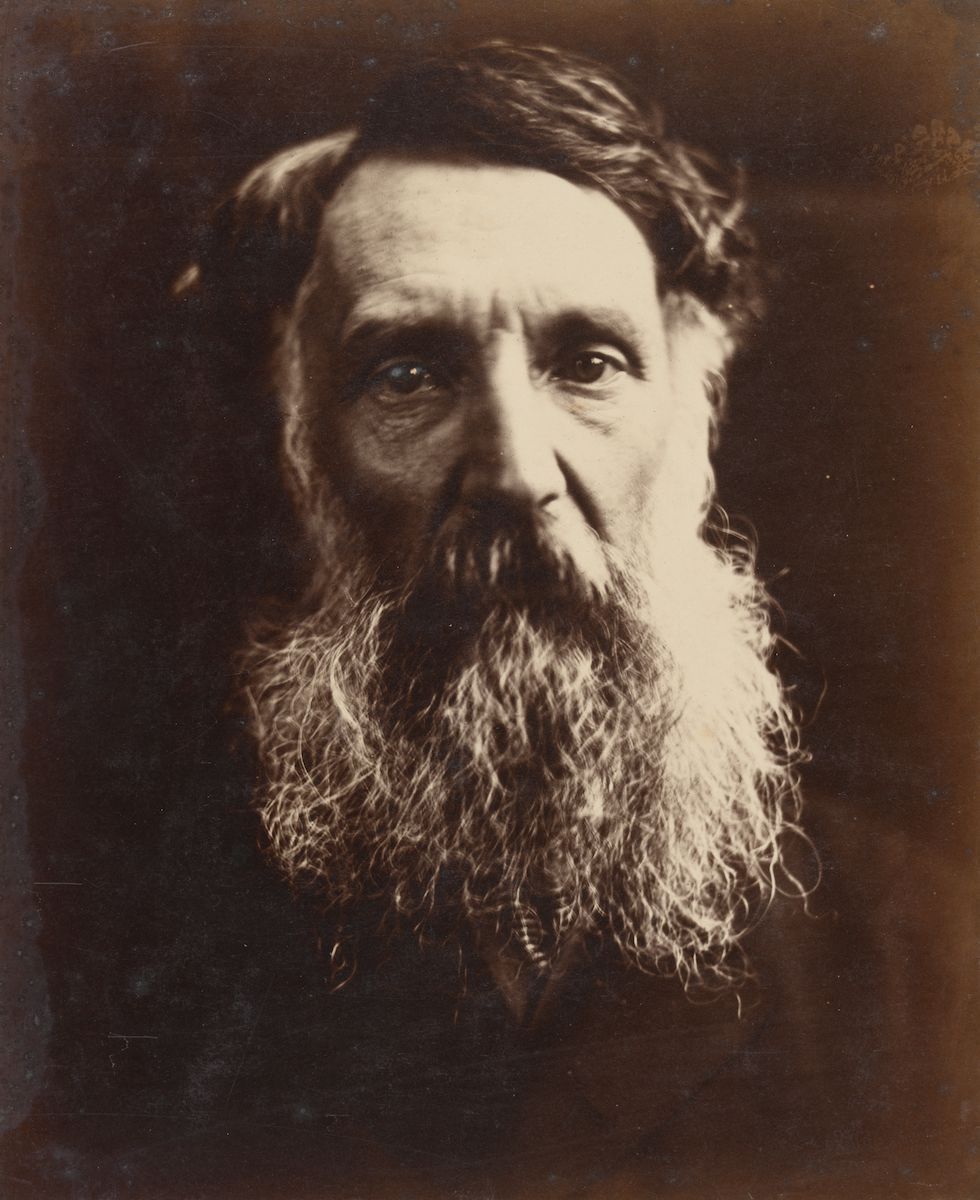

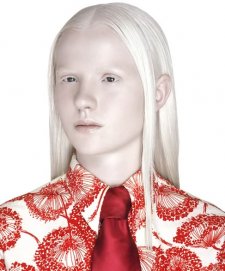

The portrait of Eyre shows Julia Margaret Cameron - a photographer of just three years' standing in the service of a medium not yet thirty years old - as a resolved and confident image maker. The large-scale quarter-length pose, strong side light receding into a dark background, undulations in printing and deliberate out-of-focus aesthetic of this portrait became the hallmarks of her unique vision and approach to image making.

Given to the National Portrait Gallery by Sir Roy Strong, former director of the National Portrait Gallery in London as a tribute to his late wife Julia Trevelyan Oman's friendship with Gordon and Marilyn Darling, this portrait is one of three of Eyre registered for copyright on 8 June 1867, the same day as Cameron's iconic portraits of Thomas Carlyle. The pictures of Eyre and Carlyle were taken within days of each other, both probably at Little Holland House. It is surely no accident that the sittings and registration coincided, given the very public links between the two men. Carlyle was a high-profile and staunch defender of the vocal humanitarian criticisms of Eyre in the aftermath of his reaction as Governor of Jamaica to the Morant Bay Rebellion.

Consideration of the two pictures yields an understanding of important conceptual achievements of Cameron's work. Yet it also allows us to see how she used a similar technique to imply very different representational meanings within her portrait project. Throughout her career Cameron was concerned with an exploration of the physical and metaphorical positioning of the body, often in relation to the objects and spaces it encounters. While other photographers located their sitters as an integral part of their surrounds, Cameron moved away from the professional studio portrait in which the client would usually be shown standing or seated in front of a constructed interior or painted backdrop. By displacing her subjects, Cameron created a new way of looking at and understanding them. Neither Eyre nor Carlyle can be understood by reference to a particular time, place or social class implied by a set or costume. Yet in both there is an important dynamic in play between the isolation of the head and the empty black space that surrounds it. As Maurice Merleau-Ponty observes in his Phenomenology of Perception,

it is 'the darkness needed in the theatre to show up the performance, the background of somnolence or reserve of vague power against which the gesture and its aims stand out, the zone of not being in front of which precise beings, figures and points can come to light.'

In these photographs, Cameron asserts presence and life force via contrasts of expression and inertia, light and darkness, definition and lack of clarity in and around the face. Cameron's much discussed technique of 'stopping short of definite focus' - essentially a blurring effect - is used dramatically for Carlyle but is also there in the portrait of Eyre.

Allowing readings of both recession into, and emergence out of, space, this technique might misleadingly be read as a concern to obscure an exterior appearance. Cameron's writing suggests she equated her use of out-of-focus with likeness rather than masking, referring to 'that roundness and fullness of form and feature, that modelling of flesh and limb which the focus I use only can give'. In her portraits of 'famous men', she quite naturally used her out-of-focus technique as a pictorial means of capturing realistic sculptural form, with a desire to express some kind of internal essence of truth or greatness. Thus she retrospectively wrote of her portrait of Carlyle 'when I have had such men before my camera my whole soul has endeavoured to do its duty toward them in recording faithfully the greatness of the inner as well as the features of the outer man'.

When Eyre sat for Cameron, on 4 June 1867, he was in London defending himself against a parliamentary enquiry that attempted three times unsuccessfully to bring him to trial for murder. The photographer's sympathies, and those of many of her close friends, undoubtedly lay with Eyre, and probably more importantly with the notion of the protection of Empire as a worthy and noble justification of the actions of an individual acting as an appointed representative to defend it. Photographing him at the height of this controversy she produces an emotive statement, surely approaching an early example of a propaganda image. The surface - Eyre's expression, his face - became integral to the literal public judgement of the man. By controlling the light and nuance of his gaze the photographer directs us to examine closely the surface of Eyre's face. We see nothing of the man described as 'tall, but with a badly proportioned head, a narrow chest, a speech impediment, and an awkward gait'. In 1869 Cameron wrote 'The life has so much to do with the individual character of each face, influencing form as well as expression'. To some degree and cleverly Cameron relies on Eyre's early fame as a heroic explorer in Australia to substantiate his unfaltering strength of vision.

Her image suggests a human vulnerability certainly not present in Carlyle, whose likeness is far more spectral, moving between presence and absence, in and out of focus, into the realm of ghostly apparition. In another less stoic pose also registered for copyright by Cameron, Eyre avoids the gaze of the viewer as if also to evade judgement and looks sorrowfully downward. This is a pose she repeats with several of her male sitters, for example 'Iago, A study from an Italian', although in that instance she conveys a different mood, one of meditative interiority. Whilst Cameron seems to have sought vindication of Eyre, this portrait is not evidence that she fervently believed in the intrinsic greatness of the man. Here it stands in contrast with her images of Carlyle, Herschel or Tennyson. Her portrait of Eyre speaks about power, but unusually for one of her male sitters, not necessarily his own. The image reinforces Cameron's historical reputation as a sophisticated photographer with the ability to manipulate her medium to obtain a particular representation for a particular purpose. It speaks powerfully of her ability to procure sitters at the height of their fame or infamy, and her consistent commercial instinct in having these same men autograph her pictures, in registering them for copyright, in exhibiting them and selling them. It reminds us, too, not to underestimate her political intent. This, like her feminist interest, was complicated and rarely clear-cut, but never very far from the surface.