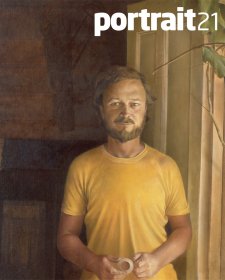

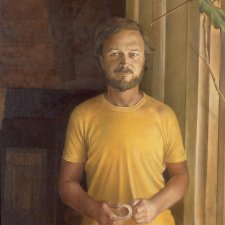

At present, greeting visitors to the National Portrait Gallery are two portraits of distinctive relevance to each other. As Bryan Westwood’s portrait of Brian Dunlop hangs adjacent to Brian Dunlop’s portrait of the philanthropist Dr Joseph Brown AO OBE, we see the artist of one work as the subject of the other.

Painted when Brian Dunlop was living in Ebenezer on the Hawkesbury River, Westwood’s portrait is situated in the old house inhabited by his friend. Dunlop stands at the open door of a cool, dark room, the door ajar to allow a shaft of bright sunlight onto the subject’s yellow t-shirt and a twist of green vine into the side of the picture plane. The portrait radiates warmth and comfort between the subject and artist, Dunlop smiling kindly at the viewer as he would have at his friend. When asked what he holds in his hands Dunlop can’t recall, musing that it was most likely something Westwood asked him to hold to enable the portrait.

A largely self-taught artist, originally in advertising, Westwood initially painted on weekends and sought guidance and direction in his association with artists such as Jeffery Smart, Justin O’Brien and Dunlop himself. Westwood’s portrait of Dunlop is informal, without restrictions. The subject was not a critical sitter, nor one with an established notion of the finished product, and this enabled Westwood to ‘find his way’ around the portrait, as an exercise. Westwood did indeed find his way, soon taking on several high profile commissions, including one in the next year of HM Queen Elizabeth II for the Federal Parliament. Westwood went on to win the Archibald Prize twice, with portraits of remarkable likeness of Elwyn Lynn and Prime Minister Paul Keating.

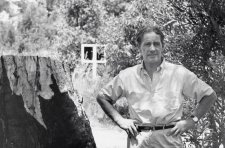

Brian Dunlop’s portrait of Dr Joseph Brown occupies a similarly private space to Westwood’s of himself. Brown sits next to bookshelves, thoughtfully concentrating upon a monograph on his lap with his dog, Bow, lying by his side and an additional book by the chair. The play of light and shadow in the background allows the viewer to imagine the room, as either a library or perhaps a study. Geometric shapes outlined on the open page give the viewer a suggestion of the subject’s infatuation, art. Art is indeed Brown’s passion; he is recognised throughout Australia as an artist, collector, art dealer and most notably a benefactor of Australian art.

Dunlop, now regarded as one of Australia’s foremost realistic figurative painters, recalls this portrait to be one of three that he painted of Brown. The one he regards as the best of his three attempts, due to an increased familiarity with and comprehension of the subject, it is characteristic of Dunlop’s acclaimed ability to portray the personality of the sitter. Throughout his career, Brown felt a special enthusiasm for portraiture and engaged as many artists as possible capture his likeness. A collection of portraits of Brown was exhibited at the La Trobe University Gallery in 1991. In the exhibition catalogue Brown wrote that ‘portraiture in this country can be seen as a distinctive art form, in which artists depict the complexity and uniqueness of the human character rather than cater to anyone’s fond hope of flattery’. His statement encapsulates the congenial nature of these portraits, the subjects of which are captured within a quiet moment of time. The mood is evoked by Dunlop in his use of watercolour and gouache, the soft mediums characteristic of his quiet, observant style. Both portraits are a gift to the National Portrait Gallery from Dr Joseph Brown AO OBE, a man whose generous philanthropy to Australian art institutions culminated in his gift of part of his collection, valued at $30 million, to the National Gallery of Victoria in 2004. His latest gift to the National Portrait Gallery contributes to the collection two portraits which share an amicable interaction between subject and artist, introducing the viewer to two individuals within their intimate domains.