'Of course it is delightful to go out on a summer's day and paint the harbour', said Thea Proctor in 1926, 'but much more exciting really to sit down and invent something that is entirely one's own, even if it is in a very small way'.

The world of Thea Proctor, opening at the National Portrait Gallery at Old Parliament House on 8 April 2005, will be the second major exhibition at the Gallery to explore the whole life of a single person, following Rarely Everage: The lives of Barry Humphries in 2002-3. Remarkably, it will also be the first exhibition at any venue of Thea Proctor's works across all mediums and periods - a long-overdue retrospective of sixty years' 'invention' by this significant figure in the history of Australian art. Proctor held responsiveness to new ideas as one of her central responsibilities as an artist, and it was a duty she took senously all her life. 'I have told students it is only by keeping an open mind that one's taste can change even unconsciously and it is a most exciting experience to realise suddenly that one has a new taste', she said - at eighty-five.

Alethea Mary Proctor's life as an artist encompassed more than half of the twentieth century. Born in Armidale in 1879 to parents who were soon to divorce, she weathered a disrupted childhood and a choppy education before beginning art study under Julian Ashton in Sydney when she was sixteen. At the Ashton school her fellow students included George Lambert, with whom she was to be closely associated in public and private over the next thirty years.

In 1903, burning with a need to learn to draw, she travelled to London, where Lambert and his family were established. She became one of his favourite models, a regular in his household, and his pupil. Although she was desperately poor, her beauty and livery nature allowed her to meet many of the leading figures of the fin de siecle art world, and all her life she was to carry with her the modernist precepts and influences she absorbed from figures such as Clive Bell, spectacles such as the Ballets Russes and exhibitions such as the post-Impressionist show at the Grafton Galleries in 1910-11. Aside from a return to Australia in 1913-14, she was to remain in England throughout her twenties and thirties.

Upon her return to Australia in 1921, which coincided with Lambert's, she immediately came to occupy a significant role in Sydney's volatile art world, and to disseminate her very strong ideas on modern art, interior decorating, fashion, costume, ballet and matters of taste in articles, lectures, formal classes, sketch clubs and at all conceivable social and artistic events. Strikingly beautiful, she never married, but supported herself into her eighties through art alone. She lived in a tiny rented flat in Double Bay, but until the early 1960s she was also able to maintain a studio in George Street, where she had lived before World War 2. In the inner city and the Eastern suburbs she became a familiar figure as immaculately dressed in brilliant purples, fuchsia and petunia shades she made her stately progress, parasol in gloved hand, seeking out the beautiful.

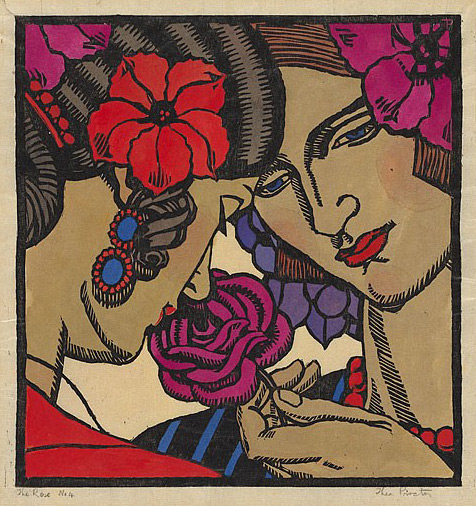

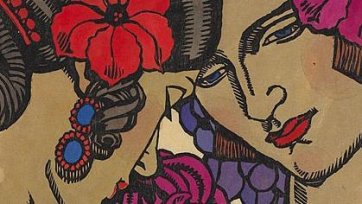

Partly through inclination, and doubtless partly from financial necessity, Proctor worked in watercolour and pencil almost exclusively. Although her mediums are consistent. Proctor's art divides into a number of distinct phases. Amongst her most charming and finely worked pieces are the fans and fan-shaped works on silk with which she established her reputation in London between 1906 and 1921. and which she continued to produce in crisper, brighter styles when she settled in Sydney in the twenties. In London she took regular classes in lithography, a method of printmaking, and came back to Australia an exponent and advocate of the technique. She is today best known for the series of woodcuts she made in the mid-1920s. a time when she worked happily alongside Margaret Preston - an artist, like several others, whom she was first to promote, and then to quarrel with, Proctor herself did not regard her woodcuts as especially significant. During the 1920s and 1930s, when she was the driving force behind Sydney's 'Contemporary Group' of artists, she made many covers for Sydney Ure Smith's Home magazine, to which she was a regular, notably didactic contributor. In the late 1920s she was one of the first people in Australia to qualify as an interior designer, and taught design to Marion Hall Best, arguably this country's most innovative and influential interior decorator to date. By 1931, accepted as one of the city's leading consultants on interiors and exponents of flower arranging, she stopped making both fans and woodcuts and created a series of brash still lifes, mostly featuring flowers or cactuses, in watercolour on silk. These stiff, cold pieces gave way to increasingly loose and free interiors, first of her friends' living rooms and then, from the late 1950s, of her own, in which she constantly rearranged small objects, flowers, cushions, rugs and lengths of fabric to create a kaleidoscopically revolving perspective. Her cat became a favourite subject at this time, as did her young female lodgers and amenable fellow tenants. Amazingly, the last significant phase of her art was a flurry of mighty nudes, which she was exhibiting and selling through the Macquarie Galleries as late as 1965, the year before she died. Throughout these shifts in focus over her sixty year career, the great constant in her life was drawing. Along with her art classes, portrait drawing was her major source of income. Children's portraits - with sitters ranging from 'the most lovely little girl with a full lower lip like a Spanish Infanta' to 'the worst boy in Double Bay' - were her particular specialisation, and her works of this kind die characterised by a stark and direct gravity that determinedly precludes the sentimental.

Proctor had a group of stalwart female friends, warm, cultivated and highly civilised women who supported each other loyally over a period of many years. In developing the exhibition, substantially in Sydney, Andrew Sayers and I have enjoyed many fascinating conversations with surviving friends and family of the artist's, who have allowed us unprecedented access to her papers and letters. Along with the magnanimity of Thea Proctor's relative, friend and copyright holder, Mrs Thea Waddell, this material has enabled us to write an account of Proctor that is substantially narrated by the artist herself, while also incorporating many firsthand recollections of her personality and methods. Our book The World of Thea Proctor, containing some ninety colour plates, many of works in private collections, will be published by the National Portrait Gallery and Thames & Hudson to coincide with the exhibition in April. Further, in a delightful confluence, the subject of our first biographical exhibition has written about the subject of our second for the book. Barry Humphries knew Thea Proctor late in her life, and he has contributed a perceptive memoir to The world of Thea Proctor that complements the essay from Andrew Sayers on her art and artistic influence, and my own on her private life, career and circle of acquaintance.

The exhibition The world of Thea Proctor will contain works by Thea Proctor from the early 1900s to 1966 including fans, lithographs, woodcuts, watercolours and drawings. It will also comprise a selection from the portraits of Proctor and other works depicting Proctor and her friends by George Lambert; a full-scale recreation of Proctor's 'modern living room' for the Burdekin House exhibition of 1929; her covers for the Home magazine; portraits of her friends and contemporaries; and letters, ephemera and personal items of the artist's. Items displayed will be drawn from public and private collections across Australia and in England.

During the exhibition, the National Portrait Gallery and the National Gallery of Australia will host a seminar exploring the work of Proctor, her friend Grace Cossington Smith and Margaret Preston, the subjects of major concurrent exhibitions in Canberra. The seminar will incorporate events at the National Portrait Gallery, the National Gallery of Australia and the Parliamentary Rose Gardens.