With the generous assistance of Ann Lewis AM, the National Portrait Gallery has recently acquired its first mirror. It is a most unconventional example. Dr Paula Dawson, a leading authority on holographic technology as an art form, has created Mirror Mirror (2004), a polished bronze mirror modelled on the ancient caryatid mirrors of ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome. This mirror will never reflect your face. In fact, it has but one reflection, the frozen and three-dimensional figure of the renowned Australian dancer and choreographer, Graeme Murphy.

Murphy is the artistic director of the Sydney Dance Company. Since 1976 he has written and choreographed thirty major dance productions and more than ten shorter works, including operas, ice-skating pieces for Torvill and Dean, and Poppy (1978), a biographical ballet of Jean Cocteau's career. He was named an Australian living treasure in 1999, and was awarded two Helpmann Awards (2001 and 2003), amongst many other internationally recognised distinctions.

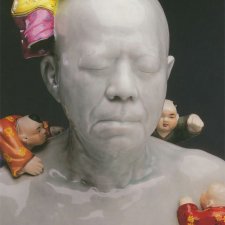

Like many portraits in the National Portrait Gallery, this portrait is the result of close collaboration between Dawson and Murphy. Both decided upon Murphy's pose, which was then scanned with a laser. This digitised information was then used to sculpt a wax figure (the caryatid, or anthropomorphic supporting stand) and generate the hologram itself, embossed with extremely fine marks from another laser. These marks, although invisible to the eye, refract light in a controlled manner to produce a rainbow spectrum, illuminating the figure of Murphy and the articulated, disembodied limbs in the foreground.

Dawson met Murphy when she was studying classical ballet as a student, before shifting disciplines into visual arts and holographic science. Murphy was well aware of the symbolic properties of the mirror, for as a dancer, he has spent thousands of hours training against mirrors.

The choice of a hologram to represent Murphy acknowledges his professional achievements as a dancer and choreographer. The sculpted figure of Murphy below the mirror (the caryatid) is connected to the holographic plate through an opening theatre curtain. Dawson and Murphy originally intended to feature a variety of moving limbs within this portrait. This concept took the form of an amalgamated profusion of human arms and legs, contorted upon the stage in the foreground of the hologram. Murphy's posed figure, with his head lowered in deep concentration, casts a shadow towards this ambiguous entity, animating it. The creature extends a hand out to reach the viewer, commanded, puppet-like, by Murphy's choreographic intentions.

In addition to the archaeological references implied by the adaptation of the freestanding bronze caryatid mirror, Dawson also links this portrait to some of the earliest known holographic mirrors. Chinese and Japanese 'magic mirrors' appear as similarly polished bronze surfaces with complex, textured ornamentation on the reverse side. When held against a light source, to deflect the beam onto a blank wall, an image appears within their projected reflection, matching features that may or may not be visible within the reversed side decoration. The reverse side of Dawson's Mirror Mirror shares the image reproduced in the hologram, but viewed from behind. Unlike the 'magic mirrors', the precise operation of which remains a subject of debate for physicists, the back of Dawson's portrait does not affect the holographic image.