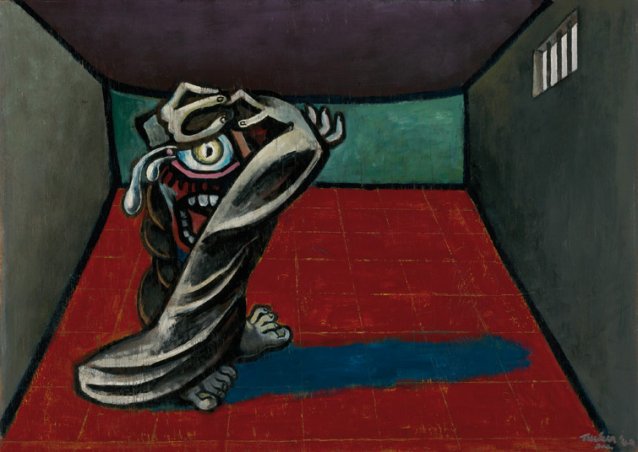

So here was I, in 1992, 1993, thinking about the influence of surrealism on Australian art, and the National Gallery of Australia, where this painting is kept and they have loaned it to us for the exhibition, have in their collection a number of works by Albert Tucker and I found them very intriguing, very affecting; and this is a painting he made in 1942 called ‘The Possessed’, but it’s the result of a number of experiences and influences, particularly in the years leading up to 1942; and we’ll return to this painting a little bit later in the talk this afternoon. So when I started working here at the National Portrait Gallery in early 2008 I remembered this work of Albert Tucker’s and I thought it would be interesting to consider it within the framework of the history of portrait making in Australia, thinking about it as a portrait of a state of mind, and Albert Tucker was very interested in ideas to do with the unconscious and he published a lot of writing about psychological ideas in the ‘40s, and we’ll get to that as well, so starting here at the Portrait Gallery I thought it would be really interesting to look at this work of Tucker’s in the context of portraiture, connect that quite strongly to his interest in psychology, and I developed that into an exhibition proposal that was supported by the Director and the Board, and it was given a spot in the program and here we are with this very interesting experience.

What I’ll do now is I’ll describe the shape of the exhibition for you. And these works by Albert Tucker, of which this painting form a part, physically in the exhibition they’re the central part of the exhibition. They’re the core of the exhibition from which other elements move out in two directions. So the exhibition doesn’t begin with this painting, it begins with an introduction to the concept of psychology and its influence on individuals here in Australia.

Now this is a photograph of a handsome young doctor named Sigmund Freud who was born in Austria and this was taken in the 1890s when he had been working for about ten or 15 years, but his works were starting to be published, translated into English, papers were being delivered. One of his major books had become more widely available. Now we can understand psychology as the study of the relationship between behaviour and mental processes. Psychology is the relationship between mind, how ever we wish to define that and there are different ways to define our mind, whether it is simply a brain, whether it is an unconscious form, energy, and our behaviour; and psychology has its origins in the philosophies of antiquity, not only in our Western cultures of Greece but are very powerfully in the cultures of India and China also. It’s been a fundamental question of human kind to try and understand that connection. It’s a connection that is also strongly based in the idea of consciousness. How is it that we are able to reflect upon our experience of not only being physically in the world, our feeling of our feet on the ground, of our bodies in the chair, but we can also reflect upon the fact that we are thinking, we are perceiving, that we are feeling; and that’s a capacity that we as human beings have in a very unique way and it’s strongly connected to ideas of the mind and in a very broad sense, questions that psychology has sought to explore throughout its history.

Freud had worked with a number of other doctors and thinkers but he was able to articulate a unique idea which was that as we go through our life we accumulate experiences and the results of those experiences aggregate within us, and they get repressed, and so there might become a time later in our life when certain behaviours and actions that we undertake that may be extreme or maybe unhelpful in some way, are the result of those accumulated experiences. Freud proposed that through the careful uncovering of those repressed experiences and feelings and emotions that a form of therapy could be entered into that could be useful to assist the mental health of the patients that he was dealing with; and that’s the basis of psychoanalysis or analysis, or as it was called in its day, talking theory; through communicating between patient and doctor to uncover these repressed desires, feelings that would then aid a more healthful outward behaviour.

Now the image of Freud that’s perhaps more familiar to us is this kind of iconic, now quite clichéd idea of what the psychoanalysis, you know, looks like. Perhaps with the beard, perhaps with his pipe or his cigar, his spectacles, and there he is even with, you know, a famed couch with its oriental rugs. So Freud’s ideas were very influential in the Western world throughout Europe, throughout the UK, throughout the US, and they also filtered down to Australia and were seen as being quite useful by what we might term the pioneers of psychology in Australia working around the time of World War I, the 1915, 16, 17, 18 period. And this portrait, which is the first portrait that we encounter in the exhibition is a delightful affectionate informal sketch of a doctor, John William Springthorpe, affectionately known as Springy and you can see that the artist has used the iconic, the kind of symbol of a little kangaroo there instead of the letters for the words Spring.

Springthorpe was very highly regarded by his colleagues. He was quite a bit older than his fellow servicemen at the time, as it would have been. He was very vocal in his thoughts.

Soldiers were coming back from the front having served in battles abroad, coming back to Australia with injuries of various types and Springthorpe was one of many doctors working in different army military hospitals and in fact some of the doctors that he worked with worked for a time in field hospitals in the Middle East, not just in Australia, and he thought that the treatment and the services that were being provided to these young men who were returning from the battlefield, wasn’t enough to help them recover from what they had experienced.

Now he encountered some of Freud’s theories in papers that were delivered at a number of conferences, and he didn’t take on board Freud’s theories wholesale. He was very sensible in that he was interested in what could be relevant to a local situation in terms of the so called talking therapy, and he was a great advocate for using analysis and psychological therapy as an aid to serve and assist the reparation of these soldiers. He wrote some very important articles in the Australian medical journals at the time. So Springthorpe represents where our story, the arrival of the development of psychology in Australia, begins, and I’m not going to refer to all, each of the ten psychologists who are represented in the exhibition, I just want to refer to a few in this instance and it’s not because they’re more important than the others, it’s just really to skip us through the exhibition if you like.

So Springthorpe and his colleagues Roy Coupland Winn and Paul Greig Dane were the first wave, if you like, and a little bit later. With the arrival of World War II in Europe and the need for many people to leave Europe for fear of persecution or worse, Springthorpe, Winn, Dane and other colleagues of theirs lobbied certain administrators in the government to support the emigration to Australia of a number of eminent European psychologists, and the same thing happened at about this time as well. Now they had a number of people in mind that they wanted the government to sponsor, assist their emigration to Australia and provide citizenship for them. They were unsuccessful in bringing more than one person and that person was Clara Lazar Geroe, and she came to Australia in 1940 with her family, and Clara Geroe is Australia’s first child psychiatrist, and Australia’s first training analyst.

Now the difference between those two terms is relevant. A psychiatrist is a person who has undergone medical training and used psychological methodologies in therapy from a medical point of view, an analysis, a psychoanalysis, doesn’t have to have had that medical background but has to be accredited by an official psychoanalytic organisation and have been accredited by a training analysis. So Clara Geroe was brought to Australia to work with the Melbourne Institute for Psychoanalysis which was established in 1941, and she was the first training analysis with that institute. Now it happens that she had her portrait painted by the artist Judy Cassab who is a very significant portraitist in Australia art, also a person who immigrated to Australia from European, and this starts to make the first connection between psychology and portraiture.

It’s interesting and perhaps inevitable that psychologists are interested in creativity as it relates to the inner world of ourselves, and it’s interesting that they should share some relationships and mix in circles, in artistic circles, and Judy Cassab, as it happens is the author of three portraits in the exhibition, and that’s not simply because she wasn’t, she certainly wasn’t the only portrait painter in Australia in the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s.

But she was one who was able to capture in her work a very vital sense of bold characterisation and in fact her portraits are defined by that boldness. This isn’t a stuffy, formal portrait of an academic. It’s a portrait that I think conveys some of the powerful presence that Dr Geroe had.

Now one of Dr Geroe’s… Someone who underwent analysis with Dr Geroe out of interest to explore and learn about analysis was young Janet Plant, and this is a photograph of her at the time of her graduation from her History Honours degree at Melbourne University and she then went back and did further studies. She was very interested in how psychology might assist progressive ideas about education; how psychology and its relationship to creativity might foster some new models of creative learning for children in schools, and with her husband Clive Nield who met her at a conference focused on the connections between education and psychology, she and Clive Nield travelled through Europe and particularly to the UK where there were some fine examples in the 1930s of progressive schools, particularly a school called Summer Hill under the leadership of A S Neill. Now Clive and Janet returned to Australia full of enthusiasm and in fact they established what is regarded as the first experimental progressive school in Australia, which they called ‘Koornong’, on the banks of the Yarra in the bush at Warrandyte outside of Melbourne; and ‘Koornong was launched in 1939 with a man named Danila Vassilieff as the foundation art teacher, and this is a portrait that Vassilieff made of Janet Nield dressed in his Cossack uniform, his family were, on the men’s side of the family, engaged in the Don Cossack army in Russia, and it captures something of the vibrancy, the readiness to experiment, the vitality of their work at the time. Vassilieff was also very good at doing hard work, physical work, and in fact he spent many weeks clearing the land helping to build the school buildings and eventually on the other side of the river building for himself out of local stone a home and studio.

And I mentioned Judy Casseb earlier who had made that very graceful and bold portrait of Clara Geroe, well Judy Casseb also painted Janet Nield in the early ‘70s. This time the manner is one that is entirely cosmopolitan, a woman very much of her times, progressive in her attire, in her fashion, in her hair cut. The colours of this portrait reflecting very much the vogue of the early ‘70s, and I don't know if some of you saw recently the two part series about the birth of Cleo magazine on the ABC a few weeks ago? To me this portrait hooks in very nicely to the key of that moment in Australia. Janet Nield trained with Clara Geroe, became an accredited analysis and had a practice in Sydney, a private practice that she maintained into the 1980s.

Now we start to get to some very close relationships between psychology and art making, and art making by some of Australia’s most extraordinary young men and women artists of the ‘30s and ‘40s. This is a photograph, we don’t know who took it, possibly a photographer called Athol Shmith, and it’s a photograph of Reginald Spencer Ellery who was a psychiatrist. He had in fact undertaken some very radical studies using malarial treatment drugs to treat body involuntary movement in psychiatric patients, and he was very successful in that and in fact became quite a high profile doctor because of those discoveries that he made with one of his colleagues. He was also very interested in the arts and literature and this photograph appears on the contributor’s page of the artistic journal ‘Angry Penguins’ magazine, which has a fairly legendary and mythic status in the history of Australian modern art.

The Angry Penguins is a term that’s now used to describe colloquially a group of artists who hung out together in a Bohemian atmosphere and included such luminaries as Sidney Nolan, Arthur Boyd, Joy Hester, the afore mentioned Danila Vassilieff and Albert Tucker, and they were supported by the Melbourne Patrons of the Arts, John Reed who was a lawyer and his wife Sunday Reed who had a home outside of Melbourne that they named Heidi, a very lovely cottage, and that home is now part of a much more expansive art museum called the Heidi Museum of Modern Art; and the original cottage is still there with the original library, with the cottage garden, there is a second home that was built in the ‘60s and ‘70s which is also now a gallery, and there’s also a brand new gallery space; and Heidi Museum of Modern Art is also a place where many of the archives and artworks collections of those artists are held and they have been a very kind lender to the exhibition, particularly with a group of drawings by Joy Hester, and I’ll mention those presently. So Ellery was a part of this intellectual and artistic set of artists, musicians, poets, writers, interested in all things modern; and we’re talking the 1930s, and they were young. They were men and women aged in their twenties, or in the case of Joy Hester a little bit younger at the start.

Now Ellery was quite a prolific writer and this book of his, ‘Schizophrenia: the Cinderella of Psychiatry’ which had first been published in 1941 by the Australian Medical Publishing Company, was reprinted by John Reed’s imprint Reed & Harris just a few eyras later. John Reed with Max Harris, who had lived in Adelaide and Melbourne during his life, a very progressive, modern poet and writer, had a publishing company that published The Angry Penguins journal and a great many books of prose and poetry in the ‘30s and throughout the ‘40s; and so they republished this book of Ellery’s, which aimed to normalise and bring to a wider understanding the condition of schizophrenia in the light of more progressive treatments, and to de-stigmatise what had been an illness that many misunderstood. Now on the cover of the book is a kind of symbolic head and the caption says ‘Symbolic Sketch by a Young Female Schizophrenic Patient’, I think, and it’s drawn from a British medical paper published a little bit earlier. Now what’s interesting is that it’s a very modern looking drawing on the front of this book that had previously been published as a kind of medical treatise but now was being published by a publishing company who were wanting to reach a much broader, progressive thinking audience.

Reg Ellery showed this drawing and other drawings as they had been reproduced in British medical papers to a young artist called Sidney Nolan and their simplicity, their primal and straight forward form, were for the young Sidney Nolan one of a number of influences on his own art. The follow up to Ellery’s book, in fact published within a year after Schizophrenia had been published, was this, The Psychiatric Aspects of Modern Warfare in which Ellery made an impassioned plea for the greater acceptance of psychology as a way to assist the social ills of what he called the psychoneurosis of war; and he asked the young Sidney Nolan if he could use one of Nolan’s portraits on the cover of the book. And this painting on the cover of the book was made by Nolan as he had been conscripted to serve at supply depots in army camps in Central Victoria in the Wimmera district and it’s a portrait of his commanding officer Captain Bilmby, but it’s not a heroic image of a soldier, it’s an image of his Captain as an unranked soldier with wide stricken eyes very clearly traumatised by what he has experienced.

And the symbol, the motif of the wide staring eyes to refer to a fraught and anxious state of mind is one that Sidney Nolan used again notably in this self-portrait painting made a little bit later, and it’s the first self-portrait we encounter in the exhibition and it connects to some others, and consider perhaps what Nolan was trying to convey by choosing to represent himself in this way, in attempting to capture his own self in a state of distress.

We saw Reginald Ellery’s photograph from Angry Penguins magazine, Albert Tucker who was a regular contributor to Angry Penguins wrote an article in the Angry Penguins broadsheet, which was an offshoot of the magazine, that he called ‘Exit Modernism’, and it was a criticism of the conservative views about art at the time, and it was also an opportunity for him to introduce some ideas that he had been extraordinarily fascinated by. He had been reading the work of the Austrian psychology Viktor Lowenfeld who was also interested in trying to access primal creative states and Lowenfeld was also interested in the role that creative art making could play for therapy, to assist in the therapy of patients who had experienced psychological trauma. Now Lowenfeld defined two types of visual artists. One type was what he termed the Visual type. For them, their art making was based on the desire to recreate what they could see, to make a realistic drawing, a realistic rendering of the external world. Conversely the so-called Haptic artist drew entirely from within and created imagery that was based on their own inner most feelings, on dream imagery, on visionary imagery that came from the inner self; and in Lowenfeld’s book there are many examples of both types of work. The ones that appealed to Albert Tucker were the work of the Haptic artists and Tucker was someone who was very interested in work by untrained artists, by child artists, by artists that at the time were called primitive artists, naive artists. We would now use the terminology of outsider art; and he was interested in work by people who experienced different mental states to those that were the social norm.

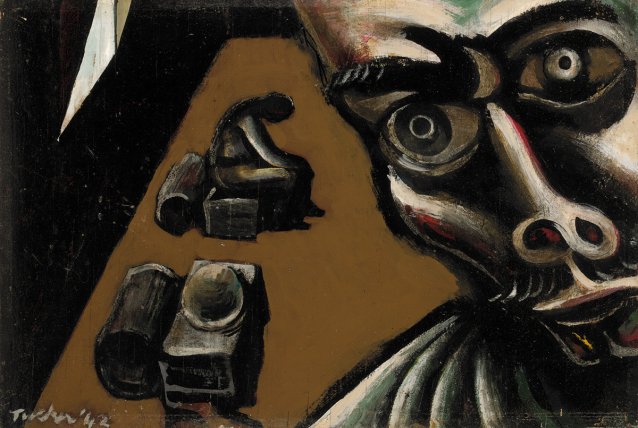

So for Tucker, he was very excited in these works and what they symbolised and they were one of a number of influences on his own work, and if you remember at the very start of the talk I mentioned the influence of European surrealism on some Australian artists’ work including Albert Tucker. This is another influence. The third influence was his direct experience of being called for service and posted at Wangaratta army camp, and later at Heidelberg military hospital; and this is one of the paintings in the exhibition. This is a self-portrait, that’s Bert Tucker’s face and he’s aged about 26, 27 when he’s making these paintings. He was called up for service in 1942. He was first posted to the Wangaratta army camp which was set up as a temporary camp in the show grounds in Melbourne, and the showground facilities were in animal pens and it was bitterly cold, it was winter time. Tucker has recalled many times how rats would scurry across you in the night. He absolutely hated it and as this image makes clear, he viewed that experience as one of isolation, it’s a very stark rendering of an experience that he found very uncomfortable, and the figure in the background sitting on his pack looks equally unhappy to be there.