Christopher Chapman: Thank you, Helena. Welcome everyone. Thanks for coming. We’re very pleased to have with us this afternoon three esteemed psychoanalysts: Dr Reg Hook, Dr John McClean, and Dr Deborah McIntyre. And they’ve agreed to share with us their responses to the exhibition Inner Worlds: Portraits and Psychology.

Now, the format that we’ve decided to follow this afternoon is very straightforward. First of all I will ask each of our guests to speak a little bit about their own area of interest in their own work, and then I’m going to ask them to reflect on the exhibition and what aspects of the exhibition and its themes they have found to be of interest from their point of view as practising analysts. And then, as I said, we’ll have some time for open discussion.

The exhibition Inner Worlds begins by recognising the contributions made to Australia by ten pioneering women and men of psychology, and it’s a very important part of the gallery’s role to recognise the achievements of unique and outstanding individuals and groups whose work has been influential in shaping our society and culture. And one aspect of the feedback that we have received with this exhibition and the accompanying book is that people with an interest in psychology in a broad sense, or who work in the area, are very pleased that this important work is being acknowledged, and the National Portrait Gallery is very pleased to be able to acknowledge the important work made in this field.

So lets start our speakers. Reg, could I ask you first of all just to speak a little bit about your own work and your own particular area of interest?

Dr Reg Hook: Yes, thank you. Now, as a psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, this exhibition has been very interesting to me, and that for a number of reasons. I first began psychiatric work at the Repatriation … what was then the Repatriation General Hospital at Concord in New South Wales, but as a medical student during the Second World War I would often go for bike rides on Sunday morning, and I watched this hospital being built as the 114th Australian general hospital, being built for the defence forces to deal with the casualties which they were anticipating.

In 1955-56 I started working at that hospital, and it was Repatriation Hospital then. And I came into contact with servicemen and women and which … who had served in the two wars, and also in the Korean War, and also with war widows. For some time I was in charge of the neurological ward, and I saw some of the consequences of injury to the nervous system that had occurred.

One unfortunate man who had been serving in Korea had a psychotic breakdown, and he must have been admitted to hospital because he fell from a window when he was under delusions of … the word hallucinations. He was chasing fairies out of the window, and he fell, fractured his spine, and sustained paraplegia. But it’s not really recognised just how traumatic war can be for people who are perhaps psychologically not prepared for it.

I’ve more recently seen a man who served in the British Army of Occupation in Germany, and he had a breakdown when he was offered a bayonet for bayonet practice.

The thing that interests me about this exhibition is that I did know several of the people whose portraits appear here personally. Tasman Lovell was the Professor of Psychology at Sydney University when I did his first year … attended his first year lectures in 1940. He was a very friendly, very personable sort of a man, and he seemed to stand very close to the early days of psychology because he’d been studying in Germany, and we heard about William James and Wilhelm Wundt, and Titchener. And they were right at the … really right at the beginning of psychology as an academic discipline. And Tassie, as he was called, seemed to … he belonged there.

He was a very friendly, very easy person to speak to. On Friday afternoons, though, one might see him walking down Science Road, Sydney University, with a golf bag over one arm, and a case in the other, going off to his favourite haunt for a golfing weekend.

I also knew Ernest Burgmann, who was the Bishop of Canberra and Goulburn. I’d known him in the 50’s and … 40’s and 50’s before we moved to Canberra. When we came to Canberra in 1960 I had a good deal more contact with him. He had … I had been working in the child guidance clinics in Sydney, and he was very interested in child guidance, in doing something for children in Canberra. He put me in touch with people who were similarly concerned. The Education Department, which was then run by the New South Wales Department of Education, had set up a child guidance clinic, actually, in the Hobart Street public school. It was staffed by a psychologist and a social worker, and I was appointed to it as a consultant.

Bergie, as he was affectionately known, was interested in many different social issues, one of which was marriage guidance. So he set up an Anglican marriage guidance council at St Mark’s Library, and I had to … I played some part in the training the counsellors. Canberra was then a very much smaller place than it is now, of course, with a population of probably 30 to 40,000, and nothing west of Red Hill except, you know, a golf course and a cemetery.

Burgmann grew up in the Taree district of New South Wales, and he began to earn his own living as an axeman in the forestry industry. And this was a skill he never lost. A story is told that later on, when living in 26 Margaret Way, old Bishop Thorpe, he was alerted one morning to the sound of an axe, and he went out to see what was going on. And the story comes from the workman who … he was wearing his purple cassock, and the workman said that, “An old codger in a purple dressing gown came out and showed us … gave us a lesson in axemanship.” This was very typical of Burgmann’s very practical and down-to-earth approach to life.

Although well underway before the way, the left wing movements of Socialism and Communism gained momentum. The Russian Revolution, of course, took place in 1917 and peace movements sprang up all around the place, in Britain and Australia of course. And the links were made between the capitalist system and the war, but the armaments manufacturers were … of course were blamed. And notable figures were involved, including Bertrand Russell. Freud of course was concerned. Aldous Huxley wrote a pacifist encyclopaedia.

Several of the people represented in this exhibition were social reformers on the left side of politics: (9:09) clearly, Burgmann too, though Burgmann supported pacifist efforts, he himself was not a pacifist. The others could all be said to have been left-leaning liberals.

Christopher Chapman: Thanks, Reg. I think now if we could move onto …

Dr Reg Hook: Okay. Righto.

Christopher Chapman: … John. John, can you just talk a little bit about your current interest in the field?

Dr John McClean: Yes. Thank you, Chris. I’m a psychoanalyst in private practice, so exclusively seeing adults (9:41) for a long time in … both enjoying literature and films, but using literature and films to discuss psychoanalytic issues as part of teaching and outreach activities in Sydney, and I’ve been involved in that sort of thing for many years. I think as a sort of an introduction to my thoughts about this exhibition, I’ll just say a few words about some contemporary views about dreaming, because I think some of the works lead us straight into that realm.

Many of you will know that Freud really came across the whole unconscious realm within us by way of dreams, his own and those of his patients, and dreams form a very significant part of our work. His initial formulation of dreaming was that it was really a kind … dreams were a way of disguising unconscious mental life because what was unconscious was too disturbing, too embarrassing, too infantile, and if those thoughts came into our mind while we were asleep we’d wake up. So the idea of dreams was predominantly a kind of repression and disguise and covering up, so what turns up in the manifest dream needs to be deciphered.

That’s still true, but there … since that time I think we’ve got a broader, deeper sense of what the process of dreaming is, and this relates to works of art. I think we now have a sense that dreaming is a process that’s going on in the mind all the time, day and night. It’s a way of processing our emotional experiences all the time, and at night time, when we’re less focussed and less affected by what we’re seeing and doing, the mind has a chance to turn over our emotional experiences.

A favourite quote of mine which I’ll mention again, which is very appropriate in this setting, is one that comes from Kenneth Clark, the English art historian, and I think he was a curator at the British … at the National Gallery.

In one of his books I came across years ago he said he believes that art springs from those experiences that we sense are so significant that they demand elaboration, and that elaboration might take place for every one of us by way of dreaming functioning, but it takes place in the form of producing works of art too.

And what interests me is, what might the experience be that needs that sort of elaboration, that can’t simply be done in words? And this exhibition very interestingly not only looks at the pioneers of psychology and psychoanalysis in Australia, but it links it very much with war experience. Psychoanalysis became of wider interest after the First World War with so many men suffering from traumatic states, and again in the second war, but psychoanalytically I think it alerts us to this phenomenon that some experiences are so horrendous and overwhelming for those involved that it’s impossible to symbolise them to make any sense of it. What do people do under those circumstances? They suffer in all sorts of ways, but some might have the good fortune to be able to turn it into, say, some of the works of art like Albert Tucker and others here, others through poems … you know, the First World War poets; others through literature.

So I’m interested in how these two come together in this exhibition and give us, as I’ll come to perhaps in a little later on, just to see how that process that’s interesting to psychoanalysts is actually being exhibited here in some of these works.

Christopher Chapman: Thank you, John. Deborah, could you reflect a little bit on your current practice and your current area of interest, please?

Dr Deborah McIntyre: Thanks, Chris. I am what used to be called a lay analyst – that is, I’m not medically qualified as my colleagues are here. I thought I might just say a couple of words about what has interested me, what did interest me and has held my interest in psychoanalysis over many years. Just quickly, a few things that came to me was something about the nature of time. Psychoanalysis allows you time; it’s a privileged experience, really. So you meet with a patient day by day by day by day, and it does allow an experience for both parties to that to take the time to explore inner world. It’s not quick, it’s not what we present, it’s just the sort of elaboration that John is talking about. It as I said feels like a privilege.

Psychoanalysis is also about curiosity. It’s a question, a constant questioning. So as I’m looking at the exhibition I’m thinking about the face. We present a certain face to the world. Psychoanalysis I think tries on the whole to reach beneath the face, into the inner world, and is in search of something that you might call a kind of psychic truth – what is under, behind, although quite connected with, what we do present to the world. And I just thought I’d add that in a way it’s an irony that … the connection between portrait and inner worlds if you’re thinking about it from a psychoanalytic point of view, because psychoanalytic activity traditionally is not a face-to-face activity. The patient lies on the couch. Typically enough you do not look at the patient, you don’t see their face, and the patient has very little eye contact with you. So it’s a kind of interesting bit of irony I think, as we try to talk about this.

Christopher Chapman: Thanks, Deborah. Now I’m going to ask our guests to make a response in relation to the exhibition.

And Reg, you were interested in some questions around the concepts of subconscious, unconscious and preconscious mind.

Dr Reg Hook: Yes. I wanted to make a point about that, because there seems to be a certain degree of ambiguity about these terms. Subconscious could refer to anything that is below the level of consciousness. Many don’t discriminate of course, but Freud (16:15) did, and was very emphatic about it. The subconscious could refer to anything below the level of consciousness. But Freud was interested in the unconscious, as are most analysts. His name is the dynamic unconscious because it’s actively retained at the unconscious level, and it’s virtually unknowable, and it can’t be made conscious without a special effort, usually.

The exhibition is about the inner world. Well, what is the inner world? From a psychoanalytic point of view it’s about the unconscious. Freud might be described as the philosopher of the unconscious, as David Chalmers was described as the philosopher of consciousness. But Freud distinguished – and some think it was his greatest discovery – two different kinds of thinking: logical, rational thought, which we regard as normal thought, and a different kind of thinking which is found in the unconscious, and in the products of the unconscious, dreams and myths. He called this primary process to distinguish it from normal secondary process thinking. And the point about it is that normal distinctions and boundaries are lost. Time and place disappear. Before and come after and after can come before, and shape is just … size and shape are distorted. For instance, a farm tractor can be seen in a dream to disappear through a mouse hole, and things like that, which is quite absurd of course.

That asks a question about the instance of art. As a representation of our thinking, especially thinking as influenced by feeling, it can reveal something to us about ourselves. It fixes the past, so to speak, so that we can resurrect it and contemplate it again.

When Freud visited Rome in 1901 he spent a great deal of time contemplating Michelangelo’s Moses. He thought deeply and he thought for a long time about it. It fascinated him, obviously, and he fantasised about it for a long time. In 1914 he put his thoughts into writing in The Moses of Michelangelo. At the end of his life he wrote another work, Moses and Monotheism, a fantasy about Moses being an Egyptian, which seems unlikely. But Freud thought he could understand something of Michelangelo’s thought.

Now, what about art and the unconscious? Artistic representation can be quite conscious. It can be preconscious, and it can be unconscious. If it is unconscious, it is likely, I think, to take a symbolic form. This is also seen in so-called primitive art where thoughts, myths, feelings are represented graphically. But how are we to use these portraits? To recall? To teach us something about the past? To learn something of the feelings of those who made them? Some of them seem to represent the unconscious more or less directly but symbolically. Here come to mind Albert Tucker’s The Possessed. It stands out. And it’s not about a … it’s not a person, really. It’s a distorted body. Self Portrait and The Snail Fleeing by Dale Frank might also come into the same category.

In primitive art … I referred … I mentioned a moment ago, and in children’s drawings, features of the body may be distorted because these are just the things that they are interested in, just as they are disproportionately represented in the cortex of the human brain. In ancient Egyptian art, the Pharaoh was always portrayed larger than anybody else, and he was always higher up. In this series, distorted features serve a similar purpose in emphasising the feelings and understanding of them.

Christopher Chapman: Thank you, Reg. John, you were going to say something …

Dr John McClean: The Albert Tucker.

Christopher Chapman: … about … that’s right, the connections between the wartime experience and the use of art in relation to dealing with some of those psychological effects.

Dr John McClean: Yes. Just following on from what Reg was saying about where do we find the unconscious, somebody said the unconscious isn’t hidden. It’s there if you look in the right sort of way. It’s seeing what everybody sees, but seeing it differently. Somebody wrote about Freud that he’s this doctor in Vienna who listens to everything his patient says. Everything can have meaning.

So looking at some of these portraits, I think we can see … in some of the areas we can look at it with a psychoanalytic eye. I was reading the … before I’d seen them I was reading the catalogue about Albert Tucker and his own experience, his … he may well have had a breakdown of his own round about the time of the war, and then he went to two of the hospitals, and then the Heidelberg hospital for some of the wounded soldiers, where he became the artist in residence. And he mentioned that one of his earlier experiences at that hospital was seeing a young man who came in with his nose sliced off by a piece of shrapnel. And I think I’m quoting it correctly. This young man apologised because he couldn’t stop the flow of fluids from his nose. And something about that really caught my attention and sort of sank in. It’s the physical appearance and what it would be like to be so mutilated. And face is so important. How would it be to know in those days – the chances of reconstruction would be small.

But it was the flowing-out of fluid that can’t be stopped, and it made me think, “What if a patient of mind had a dream about that? What would I think about … what would be the symbolic meaning? Why would a dream have the dreamer think having no nose and something flowing out? What might … state of mind might that be? What might that communicate that couldn’t be communicated in any other way?”

And then I thought, “Well, what would it be like to be a soldier overwhelmed, traumatised, filled with experiences of terror, of helplessness, of rage, of having to kill someone or of being killed yourself? What would you do with all that experience? Some might have the psychological capacity to contain it, but what if it becomes overwhelming?

It sounds to me there’d be a kind of … a flowing-out, an overflow of emotional states, symbolised by this physical state; it’s mess and beyond any control that I would normally expect to have.”

And then I saw the portraits, and in several portraits nostrils are very prominent. In one there’s a head that’s thrown back with the nostrils showing. In others there are skull-like figures of soldiers. And of course in the skull the skin is there and the nostrils are more prominent. And in the possessed that Reg mentioned, it is a body; it’s a sort of screaming face, it’s some hands. There’s a cloak that’s partially around, but there’s liquid flowing from one of the eyes, and as Deborah pointed out the … what looks like a shadow actually is like a stain. Some fluid has flowed out. Now, the more I look at that, the more it’s agonised in its effort to try to wrap up, but something is just flowing out all the time. It’s spilling out, and it seems to me it’s one of the most powerful portraits in the exhibition and that Albert Tucker produced. It’s gone beyond any sort of stylised reproduction. It feels to me it is a way of trying to convey what that would be like, what it feels like.

I could imagine that that might be useful therapeutically. If someone were able to produce that, if a patient had a dream that pictured that, if they came from the exhibition and told me, “There’s this one picture there, you know, the one called The Possession,” I could imagine us using that to talk about, and it would lead us to communicating something of the feel of that state that couldn’t be communicated any other way. And the very act of two people, as Deborah said … you might work with it for quite a while together. Being able to stay with that and experience it together would be quite a different thing from spilling out with absolutely no containing whatsoever.

I remember there’s the book Regeneration by Pat Barker, which talks about Rivers’ work with some of the soldiers. I think it was following up something from that, I came across the fact that of the First World War soldiers, the soldiers who suffered most and were most traumatised were the spotters in the balloons, because they were the most helpless. They were being shot at by everybody, they had no protection, and they couldn’t shoot back. They were the absolutely epitome of helplessness, and they were the ones who ended up most traumatised, no matter what character structure or strength or otherwise that they’d had beforehand.

So that’s the aspect of the exhibition that really struck me, and how I could imagine it coming to psychoanalytic work in a psychoanalytic way of thinking.

Christopher Chapman: Thanks, John. The painting that we’re referring to, and which some of you may know – and if not you’ll have a chance to see it – it depicts a twisted figure with a single staring eye and an open mouth. And it’s … it was painted in 1942, and in fact it was a painting that began the idea for this exhibition, and embodies the exhibition for me as a curator.

Now, one of the other artists in the exhibition, Joy Hester, who was a very close companion of Albert Tucker for many years, is also represented in the exhibition with a suite of drawings, watercolour, and gouache paintings on paper that were made over the summer of 1947-1948.

When she as a young woman had been diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma, cancer of the lymphatic cells, and she’d travelled from Melbourne to Sydney to undergo radiotherapy treatment.

Now, Deborah, I understand that some of those drawings you found to be really quite effective, and you were interested in saying something about those.

Dr Deborah McIntyre: Yes. I have to … what I’m going to do I think is show you something of how I got there. The first thing I want to say is that the lights are very bright. Secondly, just before I begin, can I ask if you can let me know if you’ve actually seen the paintings? I’m going to talk about them. Not so much about the paintings, but just my experience of going through the exhibition, and what I’m hoping is that most of you will either have some contact with that already, or that I won’t actually bore you witless or, you know, be terribly confusing or obscure if I make reference to them. Basically I’m going to talk about myself and a personal experience of them rather than the paintings themselves.

I want to start by saying I appreciate the idea of conversation. As I’ve already indicated, I think what you do when you work as an analyst is you have a conversation with the patient. It’s often a skewed conversation. It’s not an ordinary one across a coffee table or anything, but that’s … you need two people to work together.

What I’m going to talk about arose from a conversation. I went with a friend and colleague through the exhibition and we talked with each other as we looked at each piece of art. The thing about looking at a piece of art is that the art does not talk back to you so, you know, this was a way we found to kind of elaborate something of the experience through a conversation with each other. It reminded me, interestingly, as we were sitting … standing and looking at these that there’s a commentator – I think it might be Adorno – something like “We think we are looking and standing and seeing, and trying to comprehend a piece of art. In fact, the great works of art comprehend us. We are seen.” And I think that was an experience that my friend and I had as we looked at this.

Very briefly, as you begin the exhibition you come across a series of photographs, a sketch and a photograph of the early pioneers that Chris was talking about. And interestingly to me, the first thing I notice is that several of them are military men. In that kind of small studio portrait you get the image of the person, but what you don’t get is what goes on behind that. So the question of how these men were fascinated by psychoanalysis, were interested in the experience of war-traumatised soldiers, where that comes from, what it is about their own inner worlds, all of that is … you have to be curious about, you have to ask a question about, because it’s not evident what’s going on with them.

Because of the studio portraiture there’s a sort of sombreness, a seriousness, austerity about these people. And then the first one, Springthorpe, I don’t know whether any of you have seen it, but it’s a little caricature, and whoever the friend who’s drawn it has named it “JW”, a little kangaroo, “Thorpe.”

So what I register at that point is there’s a liveliness that is being picked up about this man, and for those of you who might have heard the lecture on Springthorpe you will understand that he himself went through substantial personal trauma, which you might then think enabled him many years later to understand and sympathise with the trauma that many of the soldiers he was working with faced.

Next I come across the portrait of Clara Geroe, the first psychoanalyst in Australia who came out here as an émigré from Hungary. And what strikes me is that I can think of the phrase “commanding presence”. And then I notice that I’ve got a kind of military connection here that’s sort of moving along. What I also notice then is although it’s a portrait, different to the photographs, there’s something about that commanding presence that actually comes to my mind as something like “curiously asexual”, really. Interesting colours and so forth, but stern, and even vaguely masculine.

I move on to the next portrait, Janet Nield, one of the early analysts in Sydney. And here I notice something that so far I have not picked up: the erotic. There’s something about her sexual being that comes through in the Judy Cassab portrait that is not there for me in the Clara Geroe.

I think it’s interesting that at that point we meet a couple, because we’re hearing about Janet and her husband Clive. And I think that’s probably not a coincidence. There’s something about the couple and … a sexual couple that appears in my mind. Reg talked about Janet as being a questioning woman and I think, you know, she’s inviting, and I think there is something about allure and liveliness. She too is painted in a uniform, but it’s a Cossack uniform and it’s much more colourful than the olive greens of …

There’s over-sexuality I think in the patient paintings. So I don’t know how closely you’ve seen them, but there’s … you know, it’s quite there. Like, for example, another military man, this time with full, voluptuous, feminine lips. The sexuality I think is more subterranean in Tucker. So now I’ve got the image I’m kind of looking for it somewhere, you know. Like, where’s it coming, and moving and shifting? His stuff to me is much more about tension, conflict. There’s the zipped-up uniform and the bulging eyes, so you’re starting to get the sense of an inner world that is just bursting out. Somewhat held in, but still emerging with tremendous power and pressure. And I think it does raise that question and makes you think about what is inside there. And the Tucker paintings that go on, I think very clearly show what’s inside there.

The image that came to my mind … I don’t know whether any of you have seen the film Catch 22. There’s an image of a soldier all the way through that film who’s lying on the floor of a plane. They’re trying to get him to medical help. They get him there at the end of the film, unbuckle his uniform, and his guts spill out all over the floor. It’s a very effective image, and I think similar to the sense of what you get in those latter ones of Tucker’s.

At this point I’m thinking about how they understood trauma at the time, and particularly how the early analysts understood trauma.

And it was a combination of the whole aspect of destructiveness and war, as Reg and John have been talking about, but also very much holding to what they thought of as the sexual element. Sexual there not referring to genital … not the same as genitals – better way to say it – but starting with bodily experience and through the whole understanding of pleasuring the body, how that turns into relationships, affection, love, relationships with the same and the opposite sex, and so forth.

The early analysts held to that combination. Very important in terms of understanding the symptomatology that many of the traumatised soldiers demonstrated. It’s there in Tucker because you get the sense of withdrawal and isolation, which is what the analysts were talking about, that there was a retreat, and a retreat into a kind of early developmental phase, so more like childhood. And very often, this went along with a loss of genital … you know, a loss of genital potency on the part of the traumatised soldiers.

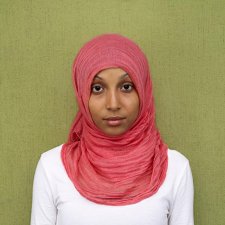

At that point my friend and I went the wrong way. Instead of coming around to the Joy Hester paintings we went into the contemporary art, and we saw the kind of … what I call the snail paintings, which you’ll probably understand if you’ve seen them. I didn’t like them. I had an instinctive reaction against them. I didn’t like the colours, I didn’t like the swirling. You know, moved on fairly quickly. We went past “the breathing man” as we called him, that Mike Parr image. I’ll come back to that at the end, but into the Joy Hester section where those striking faces are represented … and this is where I ended up, as Chris was saying, with this particular painting, which I’ll just quickly show you.

Christopher Chapman: I’ll pop that up, if you like.

Dr Deborah McIntyre: Okay.

Christopher Chapman: Sorry. I appreciate we’re far away, but we just wanted to … people to just have a memory …

Dr Deborah McIntyre: That’s the one, if you’ve seen it.

Christopher Chapman: … of the one we’re talking about. And you can have a closer look in the exhibition. Thanks, Deborah.

Dr Deborah McIntyre: Ta. I stopped in front of that one. There was something quite arresting about that, and I ask myself, “What’s caught my eye?” It’s called Face (In Close Up). And the first thing that catches my eye, I think, “What is this?” It’s a mask, so I’m thinking, “Is it spectacles? Is it a gas mask?” I’m probably thinking about the spiralling one, the trench mustard gas painting I’ve just seen and not like. Are they goggles? The eyes are looking up, there’s a kind of anxiety, a terror. And then I think, “What is that over the nose?”

So you might have just glimpsed that there or seen it. There’s some kind of noseguard, and as I’m looking at it I think, “Mmm, the image of protection is coming up.” I think about a breastplate.

And then I notice that there’s something about the contours of the face that don’t look right, that rather than going into a neck they sort of somehow … the edges of the face just come down in straight lines.

And at this point I notice my friend has wandered away, and I call her back, and I say, “Look at this painting. There’s something about this painting that’s disturbing me.” And as she came back and noticed it from a slightly different angle she said, “It’s not a neck, Deb. It’s loins.” And at that moment we both can see something that looks quite like a genital area, very undifferentiated, very unclear, but we are both at that moment very convinced of what we’ve just seen.

So it’s a very interesting experience I think, and quite like an analytic experience in that we have worked together, there’s been a kind of series of things that have emerged in my mind, come together, and I can have a particular reaction to this painting. The genitals there are very indeterminate, so it’s not clear whether it’s a man or a woman, but what I’ve got there is an image of protection, of eyes, of nose, of breast, of genitals in the face of some kind of terrifying other, person or thing.

Now, as I’ve said to people in excitement, “Look at this painting. What do you reckon?” You know, genitals, limbs, and loins. Not everybody has agreed. A lot of people have professed themselves unconvinced. And in a way, it doesn’t matter, right. The point is not whether or not this is the case, whether or not Joy Hester tries to create it, whether or not it’s totally unconscious, or whether or not it’s totally not there. But the point for me is just trying to get some understanding of how these images come to mind, where they come from, what the various bits of connecting background have been, and how it emerges into something very interesting.

The first thing that occurred to me was the “I don’t like that painting” of the snail paintings is something to do with the very disturbing swirling, sucking, mustard gas dissolution, a real threat to a sense of personality and identity, and I go, “I don’t like it.” And when I do that I’m protecting myself, I think, against a serious threat. I can also think something like the face clearly now disguises through the mask, as well as reveals, and that’s what John was indicating before. The element of sexuality, which I’ve been kind of noticing up and down, appears and reappears … re-emerges at this point, and I think about the sense that for psychoanalysis in general, the early psychoanalysts in particular, the whole area of sexuality was so contested, and felt to be, they thought, vague, difficult to discern and very easy to repudiate.

Finally, and unconnected to all of that, I’m sure, I want to go back to the breathing man, and the sort of, you know, the ending of the series. And that was the one I think I end up with. This is a man who’s … Chris has pointed out, and it tells you there, since 1982 he’s painted 1000 self portraits. And, you know, they’re on the wall there, and then he shows you through his performance video what he’s doing with them. My friend – again, very helpful – as she’s watching that performance art, says, “God, I wish he’d stop doing that. I just want to look at his face.”

And that makes me think, “Yep, look, 1000 self portraits, as many ways we have of representing ourselves all over the place, it’s still as much a protection as the goggles.”

Christopher Chapman: Thank you, Deborah.

Dr Deborah McIntyre: Thank you.

Christopher Chapman: Now, what an interesting role subjective experience has played across our discussions today. The experience of someone who has been affected by trauma of some sort, the experience of the artist, and very importantly for us the experience of the viewer engaging with, speaking to, reflecting upon the portrait or the work of art. Now, we do have some time for some questions and comments, and I really hope that some of you will perhaps like to share in our discussion. Helena and Jeannie have microphones, so please wait until you have the mike to ask your question. Yeah, we have one down here.

Male Speaker: Testing. I wanted to ask you in relation to … you’ve mentioned Freud and also your interpretations of Tucker and Hester. I was … in relation to Jung and his kind of idea that it would be possible to … it’s impossible for someone else to interpret another person’s symbol accurately. I was wondering whether you think that when you view a work of art you’re perhaps interpreting your own symbols and using the artwork as a conduit to have a dialogue with yourself, rather than actually interpreting correctly the symbols of the artist. Thank you.

Christopher Chapman: Could I respond to that first? That’s an interesting point you make, because Tucker in his later life was actually very influenced in the ideas of Carl Jung. There’s a saying amongst art curators that … and particularly with regard to portraiture that an artist’s portrait of someone else is always also a self portrait of the artist. And I think that’s very true in many of the works that are in the exhibition and in the gallery in general. I think it’s also true that a viewer of a work of art will always by necessity bring to it their own experiences and their own formations and interests, and project upon it to a certain extent. So it’s always a very complex conversation, I think. Would someone like to comment on that? Deborah?

Dr Deborah McIntyre: Well, I’ll just say that the … that’s why that quote comes to my mind. It’s “we are seen”. I think to do what I just did I’m … you know, I’m not an art critic at all, but to look at something like that, I have to lend it myself, my own inner world, and then I can see it back, you know. So I’m in conversation in large part with myself, except I have a friend to do it with. How that connects with what the artist is doing is unclear. Might connect, might overlap, might be completely different.

Dr Reg Hook: I would make a comment about symbols, that symbols we use to communicate. How do we understand each other’s symbols? It also brings up the point that John raised about communication. And I was thinking that we’ve done a lot of talking and thinking about “this is an expression of what’s going on in one’s own mind”, an endopsychic sort of thing, but isn’t it also a social aspect of this art … this … some of this art intended to communicate something?

And this comes up with regard to Cunningham Dax’s patients’ paintings … drawings, that they were endeavouring to communicate to other people something of what’s going in their minds, what they were thinking.

Dr John McClean: Can I take that up too? I … looking at Cunningham Dax and some of his paintings of the psychotic patients in hospital, and his approach was to institute the activity of painting for the patients in treatment. But it looks to me it’s rather like occupational therapy, because he makes it perfectly clear in the catalogue that there was to be absolutely no interpreting of those paintings. They were to be paintings that were completely the patient’s own production, uninfluenced by any of the staff.

Now, in one way that’s fair enough, but on the other hand that’s the exact opposite of what happens psychoanalytically. The only way … precisely because the patient might bring something, but then it’s in the exploring it together that something is articulated that otherwise would not be. So it’s not a question of, “Is that what the artist really meant?” or, “Is this the truth?” It’s rather that if it is a work of art that speaks to us, the artist is only a conduit. Something about him reaches into something that’s beyond the individual, and that’s what happens in the analytic session. It’s this patient and this analyst, but we touch on universal human themes, which is what Jung was on about. So symbolism reaches beyond the individual I think. That’s the thing that strikes me about it.

Dr Reg Hook: It’s a part of our communication.

Dr John McClean: Yes, it’s part of our communicating, you know, life and death issues, human issues, that are part of all of our lives, yeah.

Christopher Chapman: That’s a great question, and another aspect that’s quite relevant to some of the ideas in the exhibition. With regard to David Chalmers’s work, Chalmers, who is a philosopher of consciousness, whose portrait is in the exhibition, he’s very interested in the very difficulty of one individual trying to communicate an individual subjective experience to another. So it’s very definitely a question that is very relevant to all of us. So yeah, thanks.

Male Speaker: Sorry (45:18).

Christopher Chapman: No, it was great.

Dr John McClean: It’s a good one. Thank you.

Christopher Chapman: It was … yeah, no, good. Yeah. Someone else, please?

Dr John McClean: I can …

Dr Reg Hook: I have a question in the meantime.

Christopher Chapman: Yes, please do.

Dr Reg Hook: I’d like to take up, and I think it was a point John made, about the … it might have been Deborah … about the work of art not talking back. I wonder about that.

Christopher Chapman: Me too. Go on.

Dr Reg Hook: And I was thinking about Freud looking at Michelangelo’s Moses. That seemed to talk back to Freud, because he went on thinking about it, and developing his ideas about what was going on with Moses, and the history of the people, and his own personal background and what it all meant to him.

Dr John McClean: Well, I thought it was illustrated in what Deborah was telling us. Here she is looking at the picture, and has an idea, then looks again and sees some more, and has another idea, and looks again and sees some more. There’s actually an interaction going on, so it’s … I take the point you’re making but …

Dr Deborah McIntyre: Yeah.

Dr John McClean: … I think it does in a sense talk back to us as we engage with it.

Christopher Chapman: Yes, a question over … or a comment over this side of the room.

Female Speaker Yeah, I was just interested in the panel’s thoughts about the inclusion of the … I was interested in the question that was posed. There was a … I don’t know who the photographer was, but as you come out of the exhibition there’s a collage of photographs that is inspired by Charcot’s photos that were taken of patients. And I was just interested in the fact that it’s a model, and I … it raised lots of issues for me, and I’ve thought about it during the talk. And I just wondered, you know, what … why it was included and what the thoughts were people had around that.

Christopher Chapman: Thank you. The question is to do with a work that viewers encounter in the contemporary room, and it’s an image of a young woman lying on her back on a bed, and it’s a repeated image, repeated in a grid pattern. It’s a photograph. The work is by an artist called Anne Ferran, and it’s from 1989. Anne is an artist who’s very strongly interested in power relations between a photographer and their subject, particularly where that subject is in a disempowered position.

Now, that work is from a series where she re-enacted, using a model, some photographs that were produced in a home for psychiatric patients, patients suffering from mental illness – sorry, a hospital – in Paris in the late 19th century, and the photographs were taken as a medical aid. And they’ve become quite famous, because in a sense they’ve symbolised what the ailment or the situation of hysteria might look like, and they have a kind of mythic status in that sense.

Now, there are a lot of issues still unresolved today as to the authenticity of the original photographs. Were they suggested, were they acted for a particular purpose?

Also about what does it mean to say this person is an hysteric, even the assumptions that go along with that sense of description of someone? So what Anne Ferran, the contemporary artist who made those photographs, was doing was asking us to think about those questions again, as continuing to be relevant, particularly when there’s a power relation between a photographer and a subject that’s an unequal one.

Now, I included her work because it draws very specifically on a very well-known moment in the history of psychology and analysis and clinical psychological medicine, I guess, if you like. It’s not a self portrait in the way that some of the other images around that work are. It’s a portrait in that it’s a representation of a person, fictitious or otherwise. But I think it’s useful for the questions that it poses, and in fact we’ve mentioned the drawings included from the Cunningham Dax collection, which were made under clinical conditions, the information about those artists has to be withheld for legal reasons. They’re considered to be medical records. And in fact, in many cases … I was talking to one of the staff members at the Dax Foundation. Out of their collection, very few of them are attached to identifying information anyway.

So under what circumstances do we have the right to show those, to make those public? And that’s also a question that has a number of answers, you know, attached to it. Would anyone else like to make a comment?

Dr Reg Hook: Yes. It’s interesting that you made the point about Charcot’s clinic, because that takes us right back to the very beginnings of psychoanalysis. That’s where Freud changed his mind and decided he’d leave the laboratory and spend the rest of his life doing clinical work. And of course what interested him as a neurologist were these physical symptoms without any observable physiological lesion. And he set out to try to work out how people could have a physical disability or disturbance without there being any physical lesion. And that led on to his work on psychoanalysis.

Dr Deborah McIntyre: You could say, Reg, could you, that the patients used their bodies to create a work of art, in a way. You know, they sort of form some image of themselves which communicates …

Dr Reg Hook: What Freud of course concluded was that they were expressing physically things were emotional, which they couldn’t put into words.

Dr Deborah McIntyre: Yeah. So it’s a kind of self portrait.

Dr Reg Hook: And the whole business of psychoanalysis was getting this into words rather than acting it out.

Dr John McClean: I’d like to add the aspect of that that … and particularly in the situation with Charcot and his patients is a question of power and domination and submission. There’s real doubt now that the … or real thought that those particular patients all knew what was expected of them and produced what was required. They … all the girls would talk amongst themselves and then produced what Charcot wanted to demonstrate.

But you think of the situation of the hospital, the Cunningham Dax, or the photographer, that there is the potential for a power relationship: the doctor who knows, the one who tells what it means, and the patient who either rebels or fits in. Now, that can be experienced sexually, and it can be enacted sexually, so that sexual domination or sexual surrender, or a patient being seductive. It’s about power, but it can be enacted sexually. So this is where the interest in sexuality comes in in psychoanalytic thinking. We can represent our states of mind, and the way we experience relationships, through the bodily medium of sexual experience, but it’s not about sex in the simple conventional sense; it’s the symbolic.

And yes, it may well be that she’s trying to capture … the model … it’s not exactly erotic, is it, in a way, but the model is nevertheless exposed, so it captures something of that quality that probably was in the hospital as well as potentially in the photographer/subject relation.

Dr Reg Hook: The point you’ve just said leaves out the whole question of transference that Freud discovered …

Dr John McClean: That’s right.

Dr Reg Hook: … and the patient’s relationship with the analyst.

Dr John McClean: Exactly. And that relationship gets enacted without either of them realising what’s going on until it’s put into words. That’s right, yep.

Christopher Chapman: Thank you. That’s a great question. Thank you. We have time for one more question or comment. Down the front here, please.

Male Speaker: Just a comment on John’s comment about the spillage, the patient … the nose. The flowingness of that – I just wondered what is the therapeutic component of a painting as it literally is framed. There’s something about the holding of the frame. There’s this terribly fluid state, and also I guess just the static quality at one level that you’ve been able to sort of capture it in a painting or a drawing, or whatever. And I guess … I don’t know if it’s related to that, the breathing man seemed to be (53:31) because I thought he was sucking the whole time. And the … just a powerful image of sucking himself in, or this desperate attempt to sort of do that, which I thought related again to the spillage in that way. It’s just a comment.

Dr John McClean: Well, the … we saw I think when we were going round … we noticed at the initial … some of Tucker’s initial portraits were of soldiers, and they were staring eyes, but they’re fairly conventional portraits. But then there’s … on the other wall there’s the coloured ones, which come from the depths. I mean, the faces are much more agonised. Often the faces are on the side. They’re not in … they’re spilling out of the very frame. They’re not contained in the frame of the painting. So in every way you get the experience of being out of control.

What’s the benefit of that? The very fact that someone, say Tucker, could find a means of portraying that must have had some benefit for him.

But I think we know … I mean, Chris was telling us how much he was part of a whole group of fellow artists who were thinking about expressionism and new forms of expression in Australia, trying to capture ways of doing what hadn’t been done before. So he is already part of a group. Which brings us back to my point, that it’s one thing to produce these symbols, but it’s another thing to be able to use them together. The value of a dream is where it leads you in a therapeutic session, as well as having an internal step of transformation. But the next step is to be able to use that, so …

Christopher Chapman: Thank you, John. Thank you everyone for sharing in a multitude of symbols this afternoon. This, as Helena mentioned, is the fifth and final in our lecture series accompanying the Inner Worlds exhibition, but you’ll be able to find all of them as vodcasts, with written transcripts, on the exhibition website, which is accessed through the National Portrait Gallery website. It takes a week or so for the talks to be edited and uploaded, so please feel free to return to this and some of the other lectures that we have had in that form.

I’d like to thank you all for your very considered attention this afternoon, and for your questions, and please join me again in thanking our speakers, Dr Reg Hook, Dr John McClean, and Dr Deborah McIntyre. Thank you very much.