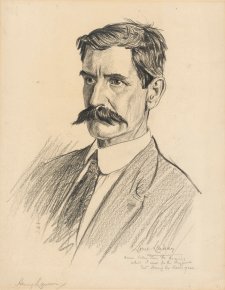

Certain European leaders (needless to name) had the effect of making certain styles of facial hair decidedly undesirable in the years immediately after World War 2. For men in the armed forces, beards remained taboo for their resistance to uniformity, though moustaches were worn by some British officers in continuance of long-established military tradition. The crew cut or short-back-and-sides style, parted and Brylcreemed, with minimal or limited encroachment of hair onto cheeks, chins and upper lips, was therefore the standard for most men of the 1940s and 1950s – indicative of the latter’s popular reputation as a time of solidity, suburbia and clean-cut conservatism.

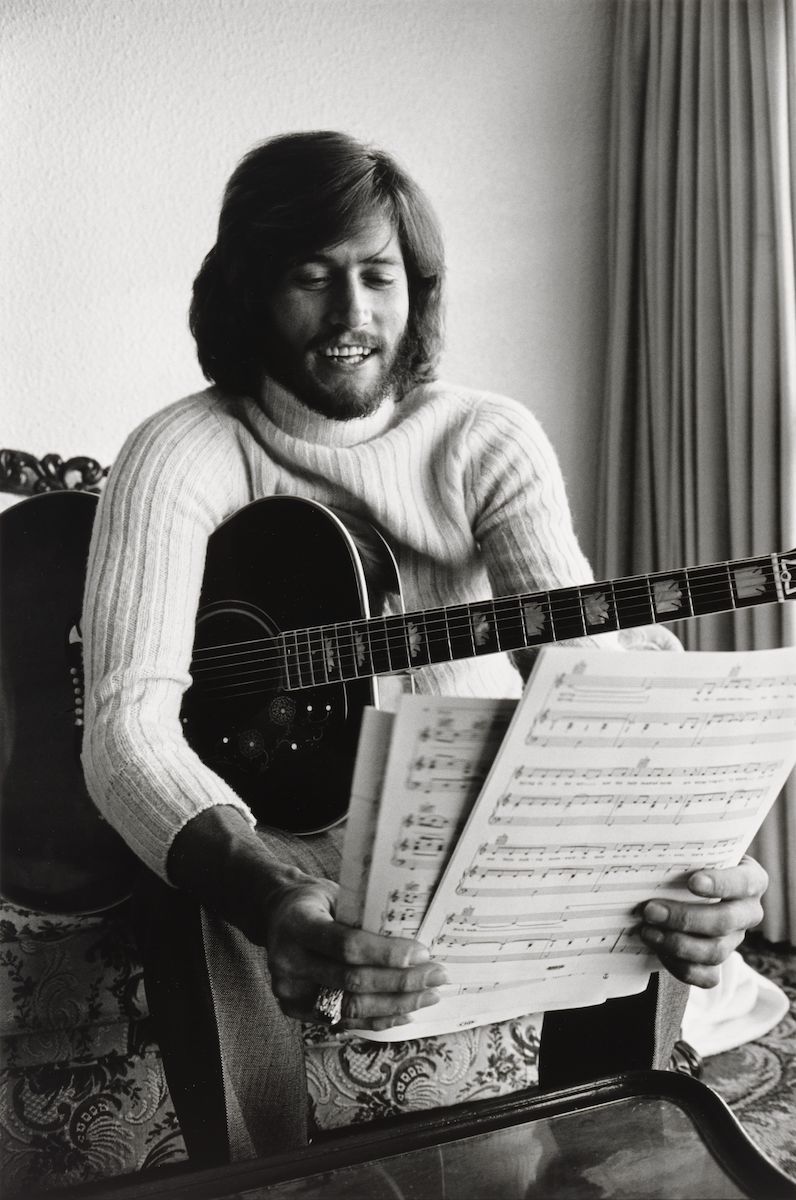

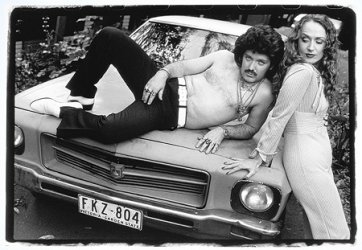

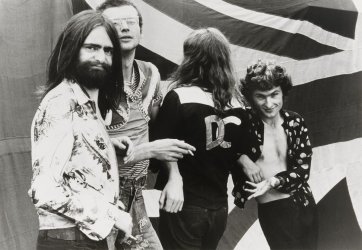

The 1950s, though, was also the decade in which beards revived their pre-1850s reputation as markers of radicalism. Beards were worn by some of the decade’s most notable and potent exponents of revolution (Fidel Castro, Che Guevara), just as they had been by their nineteenth century antecedents Marx, Engels, Trotsky and Lenin. The 1950s was also the decade in which Beatniks and others of an unconventional or bohemian bent adopted beards as a sign of disenfranchisement or individualism; and when sideburns, along with elaborately quiffed hair, were associated with youthful rebelliousness. The typical male look of 1960s counterculture incorporated long hair and correspondingly long beards. For hippies and members of other modern-day tribes, facial hair was a sign of freedom (social and sexual) and discontent with bland, middle-of-the-road existence. Facial hair was also used as a badge of political and sub-cultural allegiance for those in the anti-war, black power and gay pride movements. Hairiness, with its connotations of non-conformity, loucheness, creativity or rakishness, was the look of choice for many musicians and other pop culture figures in the sixties and seventies.

Australian men followed the fashions established abroad. Locally, however, it is sporting rather than cultural icons that are most defined as brandishers of the facial hair trends of the seventies and eighties. The thick, handlebar style of moustache – strongly associated with the gay pride era but dragged into the mainstream realm – looms large in Australian sporting iconography for its presence on the upper lips of numerous legends: AFL players Ron Barassi, Leigh Matthews, Malcolm Blight or Robert Di Pierdomenico; cricketers such as Dennis Lillee, Rod Marsh, Max Walker and David Boon; or tennis’s John Newcombe.

Ideas abound as to why the nineties and noughties have been witness to another facial hair renaissance. Some suggest that beards and moustaches, as they did in post-war times, have re-emerged in response to the social conservatism and economic rationalism of the Reagan/Thatcher and Bush/Howard eras. Others locate the twenty-first century’s fluidity of gender distinctions in workplaces, politics or family life – and the corresponding reclamation and renegotiation of traditional masculine roles and virtues – as a basis for the beard’s re-emergence, a throwback to the 1850s. Men continue to wear beards for religious, political and cultural reasons, as they have throughout history. And some cite the present-day man’s greater capacity for fashion-consciousness or interest in asserting individual style and identity as potent reasons for the facial hair comeback. All demonstrate that facial hair fashions continue to serve different and reinterpreted purposes for different times; and that beards, moustaches and sideburns will always be reflective of shifts in men’s sense of masculinity, purpose and identity.