Eighteenth century men differed from those of the preceding centuries in their preference for beardlessness. This was the typical facial hair condition throughout most of the 1700s, when wearing a beard was likely to cast one into the category of eccentric, insane or otherwise unreasoned and ungoverned. Wigs were customary for men in this era. Also called periwigs or perukes, wigs were made from human or animal hair and worn by all men, regardless of class or profession. They were available in various colours and were often powdered. By the mid 1700s, the short, tied-back style of wig known as a bag wig had replaced the elaborate shoulder-length styles of wig typical of the first part of the century.

By the end of the century, however, ideas about equality and liberty had begun to filter through to fashion. Looks and fabrics became less opulent and styles more flowing and comfortable – notable particularly in women’s gowns which, with higher waistlines that required less restraint from undergarments, began to demonstrate the era’s embrace of neo-classicism. For men, wigs fell out of favour and in revolutionary France became associated with the excesses of the idle rich. In the prevailing mood of egalitarianism, short, tousled and unpowdered hairstyles became the standard. Men’s clothes likewise became less fussy and more practical.

But whereas the trend towards shorter waistcoats and closer-fitting breeches might be argued to have been a means by which a gentleman’s masculinity was emphasised, the late eighteenth century habit of being clean-shaven gave Indigenous people cause to question the gender of the explorers and colonisers they encountered as Enlightenment ideas and imperialism lured the British to the New World. In Australia, the British reinforced their belief that being beardless was the mark of a civilised man by introducing shaving to the Aboriginal men Arabanoo, Colebee and Bennelong after they were captured as a means of forcing contact between the two communities.

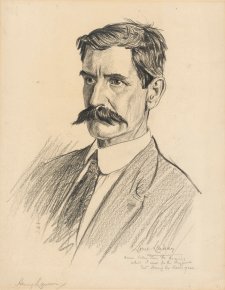

Throughout the first decades of the 1800s, the beard remained a signifier of cultural or political radicalism or other conditions eschewed by respectable society. Men’s fashions – high collars, neckcloths, high-waisted trousers and close-fitting coats – tended instead to create a romantic or dandified air. Sidewhiskers began migrating southward and along with restrained moustaches were adopted in emulation of the facial hair fashions observed by men such as Prince Albert and members of the military. Some men wore their hair in curls and used preparations such as perfumed Macassar oil to smooth or sculpt it.