I was born in Scotland and came to work in Australia, originally at the tapestry workshop in Melbourne. And even when I'm not physically traveling, part of me still lives with Scotland. So there is that kind of, in your mind moving between places. Even sometimes I'll catch myself wondering how to say something because I would automatically say it one way and then I think, well, it's said a different way here. So I have to kind of rethink. So it's about that experience of being a migrant and coming to live in Australia, but constantly referencing and thinking about Scotland. The image that I'm working on is from a photograph of a shadow, and it was my shadow over some rocks when I was traveling in Peru. When I saw the shadow over the rocks, immediately I saw this image of myself as a traveller. And it was just sheer coincidence that I had this photograph, and I was thinking about this as a tapestry. When we started talking about this project.

I took photographs, a few that are variations. Brought the photographs back and then did some manipulation on the photograph which is actually here.

So it was just slight adjustments with colour and tone and the addition of a piece in here which references the Scottish flag, the St Andrew's flag.

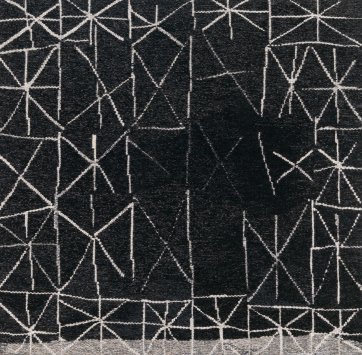

I have an enlarged photographic image behind the warp on the loom, and then I use a permanent marker to ink on just small spots on the warp to give me an indication of where shapes move and change.

Lots of people talk about their attachment to land, their sense of being deeply connected to where they live. And because I've moved, I neither feel that here or now in Scotland. I'm neither deeply connected there or here and the shadow is fleeting. It changes, it moves and that seemed to be a really good parallel for what I was thinking.

I usually don't work with solid blocks of colour. I like to change the colour as I'm working and that's why on the loom, there are a number of bobbins and each one is slightly different. There's just very slightly different whites. You start to get this kind of modulated colour, which I really like.

So, a tapestry this size is really about six weeks work. That’s six weeks with a normal day where I'd be weaving pretty much six hours in that day. I think it's a process which is completely absorbing. As I'm weaving, there are so many decisions made all the way through the weaving that really, it's only at the very final point where you see it all come together. So it's very exciting. You get so involved in what you're doing that sometimes I don't want to stop. I just want to keep going. It'll be going well and it feels like if I stop I'll just sort of break that spell. So, you want to just keep going and keep going.

This work is painting on slates, bare slates, which I actually picked up in Scotland. They were from a derelict building. The building had crumbled. It was just there in the moss on the ground. And in amongst the debris, were these beautiful, absolutely beautiful little slates. They're called wee peggies, which is the name for the tiny slates that were used in roofing in Scotland.

I did an original series of painted slates and then I was so excited I really loved the way that they worked. My sister was coming over from Scotland. So I'm saying, "Christina, remember these slates? Can you go and look for some more?" So, she arrived with a suitcase with slates in them.

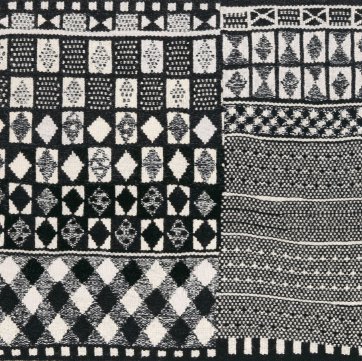

When I had them here, I started drawing on them with the white gouache, and I just loved ... it was something about the contrast between the very hard slate and the images I was drawing from Ayrshire needlework, which is a kind of whitework. It was done on a very, very fine white cotton fabric.

I like the gouache. It's got an interesting consistency because it's got a kind of powderiness that floats in the suspension of the water. So when I paint with it in a very watery solution, it starts to feel really like the grain of a very fine fabric.

There's something of that kind of softness and that beautiful stitching that's there in the traditional Scottish needlework contrasting with the slate, which of course comes directly from the land.