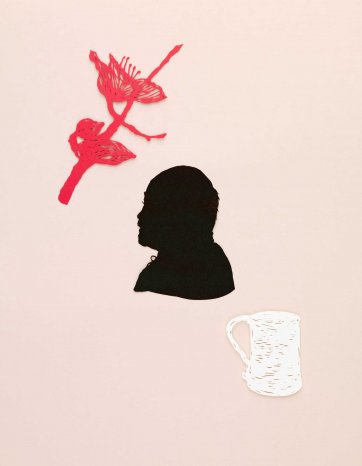

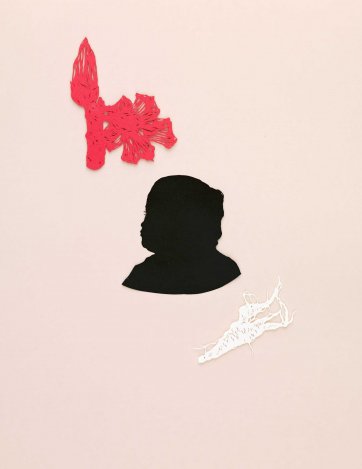

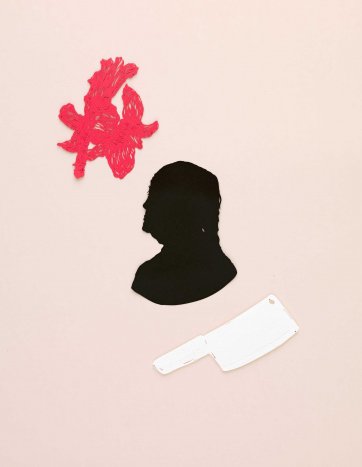

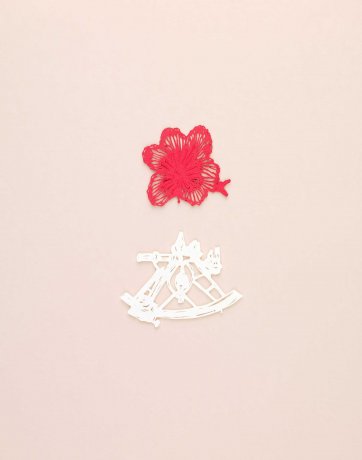

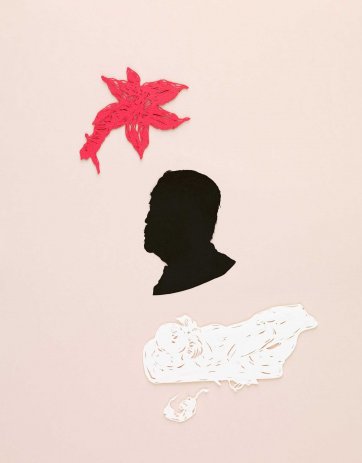

- My family, the women in the family, used to get together to practise paper crafts when I was a little girl. Whenever I do have the opportunity to stage a paper cutting class I somewhat relive that memory, so it's really lovely for me. People always assume that we pre-draw it, but we don't, I just cut straight. I draw into it with a knife. It's all tacit knowledge. It's just something that just builds up over a long time. Scherenschnitte is about paper cutting being all about dialogue, so it's considered a repository for... particularly women with varying levels of literacy so they use the cut-outs to communicate with each other and let the work do the talking. And paper cutting itself has been recognised as a form of ethnography, so it's very, very important. Typically my work is quite modest in scale. For personal use, unless somebody requests something. It's not something that you would do over a matter of size. They're very intimate things. Intimate in scale, and they're often very personal in terms of subject matter, too. I just find it really relaxing. You do your commercial work, or what has been requested by a client, and then I'm still often cutting at night because it's how I relax. My technique quite closely resembles Foshan paper cutting, which comes from Guangdong Province where my mother's family originates. And in a way, it's fortunate that it does have that relationship back to my maternal home. I don't have a lot of patience for drawing. Because I don't use a template, I'm free to cut the main form from the outside and put the detail in. I know my favourite imagery is the spaces like this. It's the pattern. More than anything, it's just the immediacy. So after I started paper cutting, there was not really any going back because you start to see how much paint and canvas costs. Particularly now, as I have a child, you can understand why so many women practised it. Because they could put it down. Even I do this now, between tending to my daughter or other household chores, I take ten minutes out to do a cut out. In a way, it keeps the work fresh. If I sit here... I used to do these large works, particularly in China, and just fall asleep at the table in the middle of doing it. I'd be cutting for hours straight. Especially when you're a young person and sort of unbridled by domestic requirements. I could do it in the evenings with very little set-up involved. It doesn't need drying time or anything like that. It's really immediate. In this exhibition, there's a series of 16 Chinese-Australians which I've depicted using two paper cutting traditions. One, obviously the Chinese style of paper cutting and the European silhouette portraiture. Just to describe the composition, in each of these images, the motif on the top is usually in colour and is of the flower emblem of the place of origin, Bombax ceiba. The red silk cotton tree. It's symbolic of Guangdong Province. The cutout composition that I have here is of Ho Lup Mun. She was a prominent woman in the Chinese community in Melbourne, from the late 19th century, early 20th century. And with Mrs. Lup Mun there's a ginseng, which is one of the herbs that she would have stocked and distributed. I have another example, Lowe Meng Kong. He arrived as a 23 year-old on his own ship to Melbourne. He was a merchant, he a number of different industries of which he became prominent in. One of them, as you can see here, this is a sea cucumber, so he was harvesting them. One of the subjects, Jimmy Ah Foo. He had a slaughterhouse, he had a market garden, but what he's best known for is as a publican. So we have a beer, sort of, cup. I think, why I did it, the motivation is largely because with no wide Australia policy, it also meant that these personal histories became invisible. So it wasn't just that they were excluded from parts of community life, they just were never recorded. They didn't exist, more or less. So it's a real privilege to be able to work with this institution to... draw attention to this whole generation of amazing Australians.