Join us from wherever you are to celebrate and reminisce with artist William Yang as he reflects on his joyous photographs of Australia's LGBTIQ+ community.

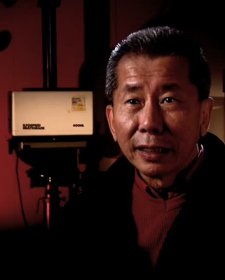

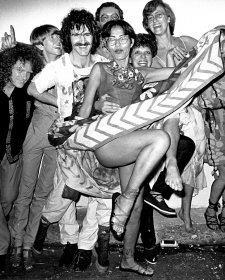

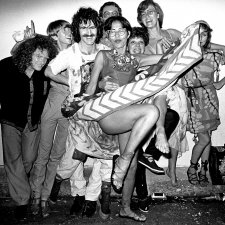

- Thank you. Even as a child, I knew I was attracted to men, and as a teenager, I went to Cairns State High School. It was the worst time of my life. People used to call me names. I wanted to be popular and to fit in, but my hair would not brush back at the sides, and there was no way I could look like Elvis Presley. I somehow knew that I was gay, but it was totally unarticulated. One day at home in Cairns, I read the afternoon paper and there was an article on homosexuality. It spelled out what the condition was and it named three famous ones in history, and I thought, oh God, that's me. The shock of recognition rather hit me like a thunderbolt. Although I had this revelation, it didn't change my life. I didn't know a single gay person, and I thought they were four homosexuals in the world. Oscar Wilde, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and me. I graduated in architecture at Sydney, at Queensland University. I liked university. It wasn't as constrained as high school, and I bonded with my colleagues, but I was still in the closet. I came to Sydney in 1969, the same year as Stonewall, about which I'd never heard. Coming to a new city meant no one knew about my past case history, and I was able to reinvent myself. I was able to come out as a gay man, fairly painlessly, although it took a period of a few years to fully transition. I met David McDiarmid and Peter Tully. They were from Melbourne and they were artists and they had style. Peter used to make funky plastic jewellery, necklaces and earrings, and in this case, a belt, and they introduced me to Linda Jackson and Fran Moore, a couple also from Melbourne, and Linda was working with Jenny Kee in Sydney, and so, we all formed a little group. Jenny and Linda had a fashion label called Flamingo Park and they had fabulous parades. David would hand paint some of Linda's fabric. I did the photos and Peter would provide the funky plastic necklaces and accessories. They're there at an exhibition on those display cones, all made of plastic. So here's the gang. Linda would call us her gay brothers and David was particularly fascinating to me because he was the first person who identified as a gay artist, and I never had that concept before. That's one of his works, and he also did a gay reading of the Doris Day song, "Secret Love" from "Calamity Jane." "Once I had a secret love that lived within the heart in me. All too soon, this secret love became impatient to be free." So he made it about coming out, and this was very much like the mood of the times, the '70s, and I put photographs like this in my very first exhibition, well, solo exhibition, "Sydneyphiles," at the Australian Centre for Photography in 1977. That's Jenny, and Linda at the exhibition. There were many photos of them, including this one of Jenny kissing Little Nell as well as scenes from gay life. It was the first time that Australian photos of the gay subculture were shown at an institution, and some people thought that they shouldn't be shown, and this is a photograph of Sylvia and the Synthetics, a performance group who appeared in the mid-'70s, seemingly out of nowhere, and they will lewd, in your face, anarchistic, and nude, they perform simulated sex acts live on stage, sometimes among themselves, and at other times, with vacuum cleaners. My favourite place in the whole of Sydney was a sauna called Ken's Karate Klub or KKK at Kensington. It was owned by a drag queen called Kandy Johnson who loved to put on shows around the pool, and she asked me to photograph the shows, and so that's how I got my camera into the sauna and people let me take photographs like this. It's amazing that they let me take them then, 'cause they wouldn't let me, I couldn't take these photographs now. People would object. Back then somehow, there was a different mood. People wanted to be, people thought it was important to be visible, and I didn't have that much trouble. and these are some other, another photograph from that genre. It's cool. "Do you remember me? I slept beside you, but left in the morning." I met Allan Booth. He was 20 and I was 36. We made love the second time we met, although had sex is more a term I've used, and then we became once-a-week boyfriends. He had others, his best friend and confidant was a person called Jeffrey, but Allan was friends with a hairdresser, a lawyer, and a theatre director. For my generation, society had loathed the homosexual, and we had absorbed this loathing, even though it was directed towards ourselves, we had internalised this self-loathing, but that was what gay liberation was all about. Liberating ourselves from society's negative opinions, but Allan knew nothing of this depression. He had come out when he was 15. His parents knew about him, but they were supportive. He lived in a house in Surry Hills that had a history of gay tenancy. There was a gay ghetto developing in the Darlinghurst-Surry Hills area, and people found that they could live in a gay household, work for a gay establishment, and fraternise with friends in venues in Oxford Street, and this situation had never occurred in Sydney or Australia before. Allan on the right, and some of the people from his household decided to have a marine fantasy party. So Jeffrey on the left, came as a wave. Lance is a blue-ringed octopus and Allan was a non-specific marine fantasy. Peter Tully came as an eastern suburbs shark. I came as seaweed. There were too many mermaids and not enough boys from Muscle Beach. Allan had a drag persona called Jinx Jones. Jinx was avant-garde and modern. While Allan was quite charming, Jinx, on the other hand, was very demanding and required a lot of attention. Peter Tully made me a hat for my birthday. It was made out of pictures of naked men. It had a lime green synthetic fur trim and he called it something on my mind. Allan threw a surprise birthday dinner for me in Surry Hills, and I was touched by his gesture. I thought, oh, we're getting serious, but a few months later, Allan told me he didn't wanna have sex with me anymore, but we could still be friends. Oh dear. There were demonstrations to decriminalise homosexual acts, which were illegal. I was politicised by the gay movement. I decided I would always be who I was. It's a thread that runs through my work. State by state, the laws were changed. First, South Australia in the mid-'70s, Victoria in 1980, New South Wales in 1984, and Tasmania was the last state in 1997, but the most famous demonstration occurred in 1978. This is not that demonstration, but I've reconstructed it. 53 people were arrested at a Mardi Gras march and thrown into Darlinghurst jail. Some were beaten. This marked the inaugural Mardi Gras, and people from that original march are called the 78ers, and so after that, there's always been a Mardi Gras parade. and in 1981, Peter Tully wore one of his urban tribal wear outfits to the Mardi Gras parade. That's Allan, Cindy Pastel and John Yakalis. There are only a few floats, the boys from the Midnight Shift, the disco, the boys from the Fitness Exchange, the girls from the Lesbian Line. Gay Aborigines, and this lesbian couple begged me to send them this photo, which I did, but I didn't have one of them themselves together, and it made me realise that representation is terribly important for a marginalised group. I've done workshops, there's always a couple that say that they're terribly hurt there's a same sex photograph of them, and their partner is not on the mantle piece with the other family photographs, and anyway, this was the photograph that was everybody's favourite from that 1981 march, gays and lesbians together, out and proud, and so the next year, 1982, Peter Tully got a $6,000 grant from the community section of the Australia Council to start the Mardi Gras workshop, and he became the artistic director of the parade. He gathered together his slaves. Sorry, I didn't really want this music on. They pulled together the giant figure of Edna Everage down Oxford Street. Tully had a team of helpers and under his tutelage, Mardi Gras quickly developed into the prototype of the modern Mardi Gras, then there was abstraction, colour and movement, and a certain innocent joie de vivre. Gays had taken terms like fag and owned them, and in so doing, they had taken the derogatory meaning from the word, words like poof or fruit, or pansies. As you probably know, the pink triangle was the insignia of the Nazis, was the insignia the Nazis used to denote homosexuality in the camps, the gays had seized upon this pink triangle as an emblem, and there were lots of them in the '80s. Sydney gays used pink triangle sunglasses, an opera house hat, and an inverted Harbour Bridge to make a smiley face. This is one of the first lesbians to dance bare-breasted down Oxford Street. A group called the Cycle Sluts from San Francisco, came to Sydney to perform, and so they created this look amongst Sydneysiders and these were the first gay Asians I photographed, and to be honest, I didn't identify with them as I was more of a activist. An early version of lifesavers, the Gay Cronulla group, I think the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence was a satirical order, but they took themselves very seriously and they were like a real order, and that were always asked to bless many of the gay events Doris Fish in the fat suit on her fish-mobile with Jackie Hyde with the lilac hair and in the crown is Doris's mother. Michael O'Halloran won best costume for this outfit, and since the gay ghetto was in Darlinghurst, there's always been affectionate depictions of cockroaches. This is one of my favourite photos, the way they've genderized the Daleks, and this is an image that I took at one of the parades, but I'm just talking about photography for the moment. Sometimes you just get a photograph accidentally that has got other meanings than the Mardi Gras parade, and I think that this one does. It's kind of absurd and it's provocative, challenging and yet, appealing to the imagination, and I've called it Fairy Tale as if you were confronted by a character in a fairy tale, and so it's like the other fairies. Peter Tully had a whole team behind him to help him make the floats at the workshop, and one year, Keith Haring was in Sydney, this is 1984, and he was surprised to find that the lead float to the Mardi Gras was a borrowing of his work. I don't think he was that upset. I think he was flattered by this. The big gay hat, then people wanted to proclaim their gayness, shout it out, ram it down people's throats, so to speak. I don't think people would wear a hat like this now, simply 'cause there's not that need. David was the director of the Mardi Gras in the late '80s, and this is the only photograph I have of him and Peter Tully together. David's carrying a totem of Tom Piper's Camp Pie. David and Peter exhibited at Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery in the mid-'80s. It's quite a prestigious gallery. So the cultural festival associated with the Mardi Gras had grown quite quickly. A few years previously, in 1983, I had an exhibition at the card shop, P.S. Write Soon in Oxford Street, and there were 12 other photographers who each had exhibitions in venues in Oxford Street shops, It was the beginning of the cultural festival associated with the Mardi Gras, and in 1989, Cath Phillips opened the Big Gay Art Show at the Tin Sheds. Cath Phillips was the first lesbian to become president of the Mardi Gras, and in 1991, gay men and lesbians danced on stage to a Madonna song, "Express Yourself" at the Sleaze Ball, and they were wild scenes backstage. Mardi Gras had become a coalition of gay men and lesbians, and with the lesbian president, more lesbians became involved in the Mardi Gras. This photographs in the Australian Love Stories exhibition, Dykes on Bikes became the lead float and has remained there till this day. There were truckloads of lemons. Black lemon lover was a subset of lemons, and this large vagina appeared on Oxford Street, quite a realistic depiction I thought, not that I'd know. Pip Playford made this float called "Look, Mom, I'm on TV." In the '90s, the Mardi Gras became big in every sense of the word. That's Ron Muncaster on the right and his partner, Jacques, and Ron would always make an extravagant costume for each Mardi Gras. The televising of Mardi Gras brought about change in the '90s. Gay and lesbian got into people's living rooms. I think it had a big effect on social attitudes but in the '90s, Mardi Gras also became corporate. That's the 2010 float for youth support 2010 is the postcard for Darlinghurst and there's a sponsor's logo on the bus. At the time, there was some who thought straight people shouldn't be allowed to come to the parties, although it was an impractical idea, but people were starting to feel possessive of the Mardi Gras. Fred Nile and his group of Christians praying for rain. Now associated with the Mardi Gras parade, there's always been the Mardi Gras cultural festival Claire De Lune showed up at the Fair Day wearing a costume of living flowers. Huge crowds showed up for the dog show at Fair Day is believed. A group at the Tin Sheds Gallery at Sydney Uni where inside there was a woman's performance group. At the Soho gallery in 1996, a muscle man posed as a kind of installation, and the Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, there was a show by the famous Dutch photographer, Erwin Olaf, and there were pedestals installed in the gallery for people to stand on and displays themselves, like exhibits, very popular. Meanwhile, that same year, there was a Robert Mapplethorpe exhibition at the MCA, and so this is part of a kind of floor show where the performers reproduced some of the images in the photos and American writer Edmund White and Dennis Altman were at that opening, and that's David Marr on the left from the debate, with his partner, Richard Barrett and Dennis Watkin who was director of the Mardi Gras Cultural Festival. So it was big and the debate would fill the state theatre. AIDS ravished the gay community from the late '80s, and this is David, who had AIDS. He made works about his condition quite courageously. Late in his life, he devoted himself to these works, and it could be argued that these are his best works. The AIDS Council of New South Wales did a series of safe sex posters taken from his paintings. He worked right up until the end, then he only had enough energy to make these rainbow aphorisms on the computer. His biggest regret was that he couldn't do more work. He died in 1995. Peter Tully also had AIDS and he knew he was dying. He loved the Mardi Gras and he persuaded his friends to dress up as hags and to push their trolleys of death in the Mardi Gras parade. It was his idea of a joke. At the big AIDS exhibition, "Don't Leave Me This Way" at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, a performance artist, Brenton Heath-Kerr appeared in a latex body suit he'd cast from his own body, he was already skeletal. I hadn't seen Allen for about four years and I was in ward 17 of St. Vincent's Hospital when I walked past one of the rooms and I saw Allan and I recognised him immediately, but he had changed. He seemed like an old man. Each time he came to hospital, he'd bring decoration. He tried to add colour to those drab hospital walls and he kept a diary in which he wrote down all his hopes and fears, as well as his dreams. I think more people die of self pity than die of AIDS. I remember another entry, "I made my will today. It wasn't as scary as I thought." They could do no more for him at the hospital, so they let him go home. That was all he wanted, just to be at home, and he'd been at home for a few months when he made the momentous decision to go off medication. 10 days later, he took a turn for the worse. His whole face seemed to have caved in, and it became apparent that Jeffrey and his friends could not look after Allan at home. So he went to the hospice and on this particular day, he was in a wheelchair while the nurses were making his bed, and he had his hand over the arm of the chair, I put my hand over his. I'd already said goodbye to Allan. I told him that I loved him, and at the time he had smiled and said, "That's good," which wasn't the response I wanted, but as we were waiting for the nurses, he lifted my hand to the level of his face and he lightly dropped his forehead on to my hand. He was young when I met him years ago, and our relationship had been full of fun, zany, exciting, sexy, but never tender, until now in this unexpected moment of grace, then he went into a coma. I saw the nurse, give him a glass of water, but the water just ran out of his mouth. He didn't respond to touch. I half expected him to be cold, but he was burning with fever and his pulse was racing. Later this night, our friend Jeffrey rang to tell me, Allan had died. There were vigils, social rituals to come to terms with mass grief. Yeah, the names of the dead were read out. I knew then what it was like to be in a war where many people died. It was then when our community was at its lowest state that our enemies tried to destroy us, but somehow, the community banded together, gay men, lesbians and straight friends, and somehow we all live through this dark period. I did some safe sex posters for ACON, that's the AIDS Council of New South Wales, targeting gay Asians, and this poster, love him safely every time came out in five different Asian languages. In the early '90s, I initiated a group, Asian Lesbian and Gay Pride. It wasn't the first Asian group in Sydney, but it was the first to contain gay men and lesbians. Our first event was centred around a seminar where we discussed what it is like to be gay and Asian in a predominantly gay Anglo society, and we talked about the politics of desire, how most of the images depicted in the media of sexually desirable, people were white, and so I did a series of photographs where I tried to sexualize the Asian body, to point out that it could be desirable, too. It's one of the reasons why gay men generally don't desire other gay men. Well, it's a little known fact that gay Asian men generally don't desire other gay Asian men, especially Asians who were born in the West like me. However, it doesn't quite explain why to people who desire only Asians, these racial preferences exist, and there are popular slang terms to confirm this. Caucasians who like Asians are called rice queens, Asians who like Caucasians are called potato queens. and Asians who like Asians are called sticky rice queens. This photograph is in the exhibition might be a different version, but they're the people from my Asian Lesbian and Pride Group, and we're at the Mardi Gras, and the Mardi Gras had already been going for 24 years before gay Asians made themselves visible as a group. They we're a bit nervous about it. So their costumes are quite elaborate, and they've kind of covered themselves up, and they did a routine that they carefully rehearsed, was very elaborate as well, and they got all mixed up during the parade, doing this elaborate dance, when really things for the Mardi Gras should be bold and simple, but we didn't understand that at this time, 'cause this is the first time they'd been there. So in 2002, Mardi Gras lost $400,000. There's no continuity with Mardi Gras members or committee. Every few years, there's a completely new committee, and managing a big budget festival requires skill and experience, but also Mardi Gras was suffering a midlife crisis. The original 78ers were getting older. and the younger generation didn't seem to be interested, but it managed to survive. There are no big budgets now. It's all no frills, user-paced. Equality has always been a big theme of the Mardi Gras, and this is a marriage rights, New South Wales in 2012, but now we have a surfeit of our own gay celebrities. Matthew Mitcham, the diver. Mark Trevorrow, entertainer also known as Bob Downe, Ian Roberts, the footballer, and one year Lily Tomlin, the Hollywood actress was out here, and she had a float in the Mardi Gras. and Kylie Minogue is a great favourite with gay men, and now there's a new generation of younger lesbians who like Wonder Woman, and this photograph is also in the exhibition, called Girl Loving. Yeah, so it's a different kind of, it's a kind of glamorous version of lesbians. Here are the Fijian, the Fijian drag Queens, with the handmaidens in the background, transsexual Isaac Roberts and Lisa Parker. These are the popular villains of the day. Pauline Hanson on the left. Tony Stop the Boats Abbott, stop the floats Cardinal Pell. Think of the children, I am. I think Mardi Gras has become a marvellous, diverse, community affair, and I like the dark moments and the lighter ones too. Sydney gay men go into training so that their bodies peak on this one night of the year. At the 40th anniversary, Mardi Gras resurrected some favourite costumes from the past. Brenton Heath-Kerr's Gingham Girl, there's the sodomite jar, and the other two costumes are recreations of costumes that Peter Tully made, and for the 30th anniversary, they resurrected Vicki the Virus, a float from the late '80s when David McDiarmid was director of the parade. People living with HIV felt they had to personify the virus so that they could come to terms with it. So that's why they invented Vicky the Virus, and it reappeared at one of the anniversaries, 13 years after David had died, and in 2014, there was a big retrospective of David's work at the National Gallery of Victoria. and it was curated by Sally Grey, who was also the executor of David's will. These anodized household appliances once belonged to Peter Tully, and David had instructed others to make them into totems. So Peter was represented at the exhibition as well, these were some of the fabric designs that David did for Linda Jackson's garments, and I used a lot of my photographs as background in one of the rooms, and this is one of David's work with Mylar, the reflective material which he used quite a lot. So Sally Grey also brought out a book, "Friends, Fashion & Fabulousness" about Jenny Kee, Linda Jackson, David McDiarmid and Peter Tully, "The Making of an Australian Style." So they have been acknowledged in that way, then in 2017, we had the same sex marriage postal survey. This was a GLBTI rally outside the town hall. I had never seen such a big crowd and this isn't all the full crowd because it's stretched around the block from this street, and then we all gathered at Prince Alfred Park in Sydney on the 15th of November, 2017, for the results of the survey. There was a bit of uncertainty, then came the announcement. Yes, 61.6%, no, 38.4%. We had won. Within seconds of the announcement ending, the producers pushed the real John Paul Young on stage and "Love Is In The Air" was played over the loud speakers. That's Karen Phelps and Jackie Stricker, her wife on the right, and that's Magda Szubanski on the left, and I think, Magda Szubanski's interviews on television was actually this, one of the reasons why we won the vote. She was just so good at making our demands understandable, and of course, that's the real John Paul Young singing. High-profile lesbian couple Virginia Edwards and Christine Forster embraced while Irish activist Tiernan Brady gave a shoulder hug to Alan Joyce, Qantas CEO who had personally donated $1 million to the campaign. "Love Is In The Air," the history of Sydney and Australia's gay community. and the Mardi Gras is an object lesson on how social change can occur. At first, there has to be protests and loud shouting to get our voices heard, then continued visibility in the media and in our daily lives eventually leads to acceptance. It takes a long time. It's 50 years since Stonewall, but change can occur. Yes, there is much to celebrate. Thank you.

- [Moderator] Thank you so much, William, that was wonderful. We've had an outpouring of love, both on-site and online for that presentation. It was amazing. Did anyone in the audience have any questions that they'd like to ask William? We may be able to take maybe one or two before we finish today. One question.

- [Audience Member] Hello, William.

- I think it's wonderful, the photos, over the years. How do you get around? I know this is sounds like a really boring question. How do you get around consent?

- Well, I can't ask everybody. I can ask, obvious, I can ask about obviously provocative photographs, and usually I don't have trouble with them, for example, there was a person called Rod Sydney who had pool parties or summer parties where a lot's going on, and I would consult with Rod, he knew everyone, to see who to leave out, for example, when I showed them, but I do get trouble and I think that if you show a lot of work about our communities, there are bound to be people who you don't, you can't reach, and so, if they complain, I'll just take the photo out, I don't mind doing that, but it's kinda something that you can't predict because it's always a surprise when some people say, how dare you, or all those kinds of things, they're usually not revealing photographs that you could say, oh, someone might have trouble with this, but generally, even from the beginning, well, there were two things happen at the beginning. Let's talk about the '80s, but a lot of people didn't want to be published because it was still, there were consequences to be, to be paid if you, so if you were a teacher and you are out, so usually, I'd ask people then if I was going to put a photo up that said that that were gay, but now there's too many people, and now I think that, it's not such a big deal now for a person to be kind of gay in public, but yes, so the short answer to the question is it's too difficult to ask everyone, but I'm happy to delete things.

- [Moderator] Thank you, William. We did have one question from our online audience and that was from Marzia who would like to know what advice you have for younger photographers, documenting activism around the LGBTIQA+ movements, especially when they're from marginalised communities themselves and may not feel like they have a place in any community.

- Well, I could give them the advice that I give photographers rather than them, which is just keep taking photographs when you've got them, just keep taking your photographs, and eventually, you'll get better at it, and eventually a story will emerge from the photographs, and it's to do with your personal choices, 'cause you do have personal choices when you take a photograph, but I think it's important to get back to this question. I think it is important for people to document their own communities. In fact, that's exactly what I've done here is no one paid me to take those photographs, and in fact, a lot of people advise me not to waste my time with the gay community 'cause it's just a phase I'm going through. Being Chinese and gay community are two major themes in my work, and I think that people are more open to a display of these photographs than they were in the '70s and '80s when I first started showing photographs like this, in fact, I think there's been a lot of prejudice, because of this, in my work as a photographer, since then, and I think a lot of it has to do with the content, the gay content, although people probably wouldn't say that straight off. They wouldn't say, oh, don't do gay or something like that, but I think that now with marriage equality, there's probably more, people are more open to the idea of gay or something. Still, there are many, in short, not everybody embraces it.

- [Moderator] Thank you and we do have one final question from one of our Zoom members, Neil. Neil has attended just about every virtual programme that we've ever done, so we consider him one of the family. Neil was wondering if you thought the commodification of Mardi Gras pride has been a positive or a negative for the community and why?

- Well on one hand, like the Mardi Gras got its own life, and it's gone in this direction and it's still alive, a lot of people, this is not exactly me, a lot of people would like it to be more grassroots, well, it just hasn't gone that way is all that I can say. So without even having a strong opinion, Mardi Gras is still going and I could say, I go to the parade, not every year, but occasionally, and it's quite vibrant. There's lots of young people there. They like young people as well, and it's quite a good experience, but it's not like it used to be, and probably, the world doesn't travel backwards. It always travels forward, and so I'm happy that it's still going.

- [Moderator] Thanks again, William, for a really wonderful cold Canberra afternoon and taking us seriously on a journey through your life. So it's been a privilege to be here and thanks to all of our on-site audience for coming in and just flagging that our next go at a hybrid event is on the launch weekend of our Living Memory, the photographic portrait prize event. So that's the last weekend, it's that weekend, end of July, beginning of August. So keep that in mind to perhaps come back again and please join me once again in thanking our wonderful speaker today, William Yang .

- Thank you.

Related people

Related information

William Yang

'Feeling comfortable as a human being'

Portrait storyWilliam Yang on his heritage and becoming a photographer in the 70s.

Patrick White by William Yang

Portrait storyAn interview with photographer William Yang who recalls his encounters with the author Patrick White.

Lust for life

Magazine article, 2008Celebrated Sydney-based photographer and performer William Yang was commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery to produce a new performance work that premiered at the opening of the Gallery's new building.