Hello everyone, and welcome to 15 Minutes of Frame, our cross continental conversation series that brings together the staff of the national portrait galleries from around the world. We're going to go behind the scenes, get to know what makes them tick, and we have a fantastic lineup today of panelists from Scotland, New Zealand and Australia and a terrific topic. So we're going to kick off with our conversation shortly. This evening, I am broadcasting from the beautiful countries of the Ngambri and the Ngunawa peoples and I'd like to pay my respect to their elders past, present and emerging, and I'd like to extend that same respect to any of the lands on which you're coming to us from today. My name is Gill Raymond, and I'm going to be the host of the conversation today. We like to make all of our virtual programs here at the National Portrait Gallery in Australia extremely interactive, so if you would like to ask a question about panelists this evening, please pop it into the chat or the Q and A function in Zoom or into the chat function if you're joining us live on Facebook. All right, let's meet our panelists. Joining us bright and early from Edinburgh is Christopher Baker. He is the director of the European and Scottish Art and Portraiture at the National Gallery of Scotland. Paul Johnson is a curator at Te Pukenga Whakaata, New Zealand's National Portrait Gallery, and I do apologise if I've mangled that pronunciation and Joanna Gilmour is our very own curator of collection and research here at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, Australia. Now, the topic that we've selected for their conversation today is a meaty one. We've chosen power and portraiture. And what a can of worms we're about to open this evening, and this morning, if you're coming to us from overseas. There's so much to unpack in this topic. Not least of all is the fact that portrait galleries themselves are very much embedded in and came from, were born from particular power structures. So let me throw over to Jo and she'll kick off the conversation.

Here we are. Can you guys both hear me?

It's good.

Great. Well, hello to you both. Good morning to you, Paul. Sorry, good evening to you, Paul. And good morning to you, Christopher. You really drew the short straw in having to get up at quarter past six in the morning in Edinburgh to tune in to join us for this conversation.

It's lovely to be with you, so no problem.

Great, and we're really sort of looking forward to having this conversation, although as Gill has sort of warned us, I think it could be potentially a bit of a can of worms. But what I thought we'd do this evening is sort of based on that kind of warm up conversation that we had a few weeks ago. I've kind of pulled out a few sort of meaty themes that I thought we could get started with if you like, and then we can sort of take it in whatever direction that it chooses to go in and the other thing that Gill mentioned in her intro is that sort of thing that sort of I think came through very strongly from our conversation a few weeks ago, was that idea of, you know, colonial legacies and it's always been of interest to me that there are very, very few national portrait galleries in the world and the bulk of them that exist are in places that are English speaking countries and also places that have a British colonial history, so Australia-New Zealand, the United States being the two that I'm thinking of in that sort of context and that's always really intrigued me. And I was wondering if you wanted to sort of, if you wanted to say something about your feelings about that sort of that characteristic of portrait galleries. What is it about sort of British colonial origins that makes us want to sort of stake our claim in this way and discover our identity and record our identity in this way? I'll throw that to you Paul first, if you like.

Sure. I mean, one of the things that's interesting about the New Zealand Portrait Gallery is that unlike the two galleries where you two are coming from, we are very much a kind of private nonprofit initiative that was kind of founded by just one woman who decided that New Zealand ought to have a portrait gallery. And I think that probably says something about kind of New Zealand being this country that is, has this very or at least used to have a very British centred sense of national identity. And I think this is where, you know, even conceiving of the idea that this is an institution, a country ought to have by a private individual speaks to her existing in this kind of Anglocentric British world, I guess. Yeah. I know your gallery has a very different history, Christ, which may be good.

Absolutely. So I think it's a really interesting point that you raised about the fact that national portrait gallery are confined in many ways to the English speaking world and I think it's partly because of their history and the way in which they grew up in the 19th century, very different world from the one we have now and there was strong motivations then, which perhaps we're very uncomfortable with now but we need to recognise that that was the context to do with nationhood, to do with education, and actually in the Scottish context, there's a remarkable man called Carlyle who you're probably familiar with, great historian in the 19th century. He had a very simple but incredibly powerful ideas. As he saw it, if you wanted to understand history you needed to see the faces of the people who've made history, which is a very, very powerful motivation and I think it does connect with colonialism just as you've rightly imply, but a lot of other forces that came to bear in the 19th century. And I have to say happily, of course and rightly, we've moved way beyond that, so there is obviously now something quite different, inclusive, open, not hierarchical at all, and that's as it should be, but that history is interesting and indeed important to be aware of.

Yes, and it always intrigued me, I think, is that, you know, Thomas Carlyle of course is one of the sort of driving forces behind the foundation of the portrait gallery in London in 1856. And I affectionately referred to NPG London as the mothership and I still do and even while acknowledging all of that very problematic history and those sort of uncomfortable elements of our origins. It's always really interesting to me how much of Carlyle's sort of original concept about learning about history through, learning history as refracted through individual lives and representations of individuals and learning through biographies, how that still very much resonates with me working here a long time after Carlyle was promoting his ideas and the sort of concepts behind the foundation of NPG London in the 1850s. Yeah.

Absolutely. Absolutely. The other strand of this, of course though, is that portrait galleries thrive in an environment where the art of portraiture in all its different forms is lively. And there's sort of many artists who were excited about that challenge as well. So there is the political dimension, but very importantly the artistic dimension too to all of this, I think, which is fascinating.

And I think some would argue too that, or certainly speaking here about the Australian context, that sort of idea, actually, could we have a look at one of my slides, Robert, which is, it's just a quote. So it's the only one of my slides that hasn't got any images on it. I'm not sure whether Christopher and Paul are familiar with this quote but it's the British painter, Benjamin Robert Hayden and it's a quote that I often come back to in sort of thinking about Australian portraiture specifically I guess, because I think one of the perceptions of portraiture is that, and this is something that I kind of grapple with all the time, is that it's not real art. You know, it's just something that a lot of artists did and this is certainly the case in the Australian colonial context. It's a lot of stuff that was made simply because artists were out here and portraiture was a way you could make a living, 19th century Australia particularly, up until, you know pretty much up until federation. It was very much a sort of, middle-class kind of provincial society, a very sort of opportunistic society. A lot of people who are out here A, because they didn't have any choice about being out here or who came out here because they saw it as a place of opportunity, aspirational sort of clientele, I suppose. So it was very, was ripe. Ripe territory for portrait painters. And I think just also to bring this in here as well is that other sort of very much closely related factor and another thing that sort of came out of our conversation, that we had a few weeks ago to get this program happening was once again, I think a point that you made Christopher about the implications of portrait collecting and specifically the assumption that by collecting and displaying portraits, national portrait galleries are supposedly shaping or perpetuating concepts of who is powerful and important and worthy of respect, and also shaping concepts of what type of portraits, what type of object are most worthy or most appropriate in that context. And I know Paul, you've just, if it hasn't finished already, you've worked on an exhibition, which is just about to finish, which is on that very sort of question, that notion of portraits as power, as a form of perpetuating and disseminating ideas about power and influence. Do you want to tell us a little bit about that exhibition and maybe about some of the works that you featured in it?

Yeah, absolutely. And if anyone here is in Wellington, it will be open until this Sunday. So you still have a few days left, but not very many. And maybe we could start with this image of a single coin from my sides, because I think this is something I think is quite important as context. Yeah, so this is sort of arguably the very first kind of realistic portrait in the Western tradition. And it's a portrait of Alexander the Great and like a big part of the reason that everyone knows who Alexander the Great is, even today, is precisely because he was this first person who caught onto this idea that he could kind of commission people to make reproductions of his face that actually looked like him and distributed them widely across the world. So this coin wasn't even made by Alexander the Great. It was made by one of his successor kings who took over his kingdom, his empire after he died, and this guy, Seleucus, is still making coins with Alexander's face on them because this is a way to lay claim to his legacy. And so I think thinking about currency in particular is a really interesting kind of way into the kind of ways that portraiture kind of very kind of in a very material way manifests power. This is how you know your money is legitimate even to this day, is that it has a picture and all the places that we live in, a picture of the Queen. Yeah.

Absolutely. It's the power of, I suppose, reproduction makes a portrait more powerful, doesn't it, duplication, and it's so interesting seeing coinage. I think we tend to forget it wrongly, forget about coinage and metals, and when we're thinking about portraiture, but they're fundamental and global as well, actually. And I'm struck by the fact that at the moment most of us are not using much physical money actually for obvious reasons, so that power has actually diminished a bit right now. It is so interesting and it's to do with, so this is a very simple way of putting it, but in some ways, endorsements I think actually. Endorsement of power. So just as, you know, if a portrait enters the national portrait gallery, to a degree, that is some level of endorsement but also having the head of, incredibly important head of state, let's put it like that, on a client or a metal or a bank note, it's solidifying and duplicating that power. Isn't it really?

Hmm. And you had some observations about Robert Burns in relation to that question of the reproduction of and dissemination of images.

That's right. Could we, thank you, could we kind of look at the image of Burns that's in the Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh which is by an artist called Alexander Nasmyth. Thank you. There it is. That's great. So this is a late 18th century portrait from the life. This is Robert Burns, the national poet, the great Bard of Scotland, actually painted by a friend of his, Alexander Nasmyth. And from the outset, this was intended to be reproduced and duplicated. It was actually engraved as a print in an early edition of the poet's poetry. However, it's taken on another life, many other lives, because since then, it's been reproduced millions of times on souvenirs, in all sorts of media. And this small, modest although very attractive painting has become an icon way beyond its original circumstances of creation through reproduction essentially. And it's become much more powerful than I think could ever have been originally anticipated, that's what I'd suggest, through that process.

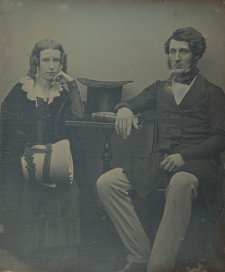

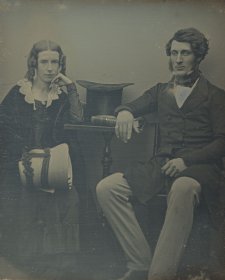

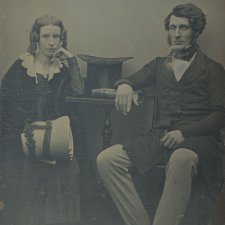

Mm. And Burns is someone, I mean I guess, an Australian or equivalent for us, in terms of the Portrait Gallery's collection would be someone like Queen Victoria. Actually, we've got an image of Queen Victoria I think somewhere. And, you know, Queen Victoria is someone who never ventured to Australia, yet she is inescapable here. There is so much of this country, yeah, that's a wonderful little carte de visite from 1860 which is on the left-hand side of the screen. So I guess this is, not that you would know it from this image, she looks like just any other sort of middle-class respectable wife and mother, but at the point that this has taken, she is possibly the most powerful person on the planet with countless hectares of territory under her control and millions and millions of people sort of for whom she was the sovereign and what, I mean, I'm fascinated with cartes de visite for all sorts of reasons. I've paired her with the lady on the right, who was a woman named Marie Sibly, who was a traveling phrenologist and hypnotist who worked on the Goldfields in Victoria and also in New South Wales a little bit in the 1860s and 1970s and I've paired the Monarch with this, you know, rather kind of a spurious show woman just sort of to demonstrate the, you know, the kind of scope of the portrait gallery's collection and that whereas there might be this conception that national portrait galleries only collect images of household names and people who were very distinguished or very powerful or very beautiful or very important or very historically significant in some way. What we're very much doing in building a collection here is not just thinking about the individuals, but thinking about the way those individuals were represented and thinking very much about the way that portraiture was practiced and consumed in all of its kind of glory for the, so we're creating a history of portraiture, I suppose. And the wonderful thing about those images of Queen Victoria, like I say, they were, they were taken in 1860 and she made what must've been a really kind of radical decision at the time which was to make, there's a whole series of those photographs. The photographer went to Buckingham Palace. He photographed Victoria and Albert and all the kids, and Victoria gave permission for those images to be reproduced en masse and circulated everywhere. And that's how the carte de visite took hold, definitely in Australia those photographs were available here if not in 1860, then definitely by 1861. So very shortly after they were taken, and it almost, it basically paved the way for the uptake of photography on a massive scale here, not just because the carte de visite was such an affordable, accessible format, but because the queen was demonstrating to all and sundry that she was quite comfortable with circulating her image and popularising herself in that way. Yeah.

I might, oh, sorry. I wonder if I might bring up, maybe we could get the photo of this portrait of the Queen being unveiled that I've put on my slides--

Yes, I was going to ask you about those. I was intrigued by those images.

And that one, they're all sipping simultaneously. I love that.

Yeah. I mean, one of the things that's remarkable, like this is, the New Zealand Portrait Gallery has a really tiny collection. I, you know, something like 200 items, and this is one of the most recent items to add to our collection is this painting of the Queen, done from life by a New Zealand painter who went over to London and had a couple of sittings with her and then unveiled and as you can see, a very kind of grandiose ceremony, this painting you can see on the back wall is actually like another painting of the Queen from the fifties, I think, like a really old one, and this is a new one. This is like the new one for the 21st century. And apparently it was commissioned by a group of young New Zealanders who wanted to express their support for the Queen and so it's very interesting just sort of to see that this is still, I don't know, there's this idea of wanting a new image of the Queen with something very important to this group of people. And it's the first painting of the Queen made for New Zealand since this one in the fifties. And--

It's interesting, it's in a traditional medium as well, because it's all on canvas, isn't it actually? So it's sort of fascinating sort of appropriateness about that.

Yeah, but I also wanted to juxtapose it with this other painting of the Queen Van we get the painting of the Queen with a cigarette in her hand please? Because I think something that's so interesting about the kind of dissemination of the image is that the person disseminating their image loses control of it. And the queen can kind of disseminate her image all she likes in these sort of official media but artists are always free to do whatever they want with her image and this painting, it's kind of hard to tell from this image, but this is an immaculately painted painting, in technical terms it far exceeds that official painting we were just looking at. Like the detail on this is incredible. And it's a painting when you first look at it, you think sort of seems like a very reverent depiction of the Queen, but of course you look closer and you see the cigarette in her hand, and I've talked to Liz Moore who painted this, now 20 years ago, and she says, she wanted to think about the idea of like a kind of secret life. That there's sort of something about the Queen that we can access from her kind of official depictions. And, you know, maybe she secretly has a cigarette every now and then and we just don't know because her image is so curated. And I think this idea of image control is a really interesting one. Yeah.

Very important, isn't it? It's interesting to see that that juxtaposition and the artistic freedom that in fact that represents, but of course the freedom comes depending upon what context the painting or the portrait is intended to be shown and I'd suggest who pays for it as well. But that seems to me a key issue here, because there's a sort of whole economic dimension behind formal portraiture, you know, greed endorsed portraiture and sort of private and more subversive portraiture that actually begs other questions. It's quite quite a strong distinction between the two.

Hmm. Maybe we should go back to that sort of spectre that was raised by the recent portrait of the Queen, of the sort of portrait of, or the question of the quality, the aesthetic qualities of the work itself, because as I sort of mentioned at the start, I think that's, you know, that's one of the things certainly that you encounter as a curator of a portrait collection is this idea that it's not real art, portraits are somehow inferior for whatever reason, either that's because they are the sort of images that we see on coins and bank notes or on telly, in publicity, magazines, those sorts of things that they only show, you know a select, it's a very self-selecting genre. They only show a certain sort of group of people or category of people. They, of course also have an uncomfortable association with factors like pride and vanity, et cetera. And fundamentally I suppose the other thing that you're always encountering especially with, if you're like me and you're dealing or prefer to deal mostly with 19th century or colonial art, they're not artworks that necessarily originate out of or supposedly not artworks that originate out of, you know, artistic genius or creative inspiration. They're the result of a rather sort of dispassionate commercial transaction between an artist and a sitter who wants to be made to look powerful or beautiful or important, or, you know, insert adjective here. And then alternatively, and this is another thing that you often encounter when you're sort of dealing in the territory that I'm often in. There's the idea that portraits are artworks that are created primarily for historical or sort of record keeping purposes. So that individuals who were significant at particular periods of history can be documented and remembered in posterity. And I suppose that is seen as effective, which is sort of, people seem to think it kind of diminishes from the quality of the portrait or the merits of the portrait as an artwork. And for me, I don't know about you, I'd be really interested to sort of hear your kind of take on this, but in interpreting portrait collections, I've sort of found a way around that to be, to acknowledge those kinds of elements of portraiture and actually sort of use them to subvert, I suppose, and to dismantle some of those kinds of misconceptions that some people in some of our audiences may have about portraiture and about national portrait galleries and what it is that we do. Do you, either of you want to comment on that sort of concept, this idea that you can actually take what is seen to be a downside and make it work to your advantage.

You've opened up a lot of questions there. My goodness, that's quite a challenge. I think two or three strands of what you said really resonate with me. It's very interesting the way you describe the power of portraiture. So there is a sort of business element to the production of portraiture as there was back in the 19th century, and also like artists who specialise in portraiture, like artists who specialise in many other different types of subject matter and genre, there are those who are not so accomplished and those who are outstanding. So there are, I think we have to recognise is there there is a great tradition of great portraiture, artistically speaking. There's also a strong issue here, it's about the commemorative role and how you have portraits project into the future status. I suppose that's a key thing. One of the ways in which we cut through that is I suppose, because of the incredible attraction and power, the visceral power of engaging with somebody else's personality and face and appearance, and perhaps with the choices they have made about how they want to be commemorated, which could be through a modest cuts vise, through it could be through a very grand painting or sculpture or it could be another media too. So there is an issue there. The other thing that, the other reason I think in particular, why portrait galleries are and portrait collections are more exciting and engaging and important than ever is because of the digital age we're in. We all take and make and are the subjects of portraits, or not everybody, but many do, because we have phones in our pockets that allow us to do that. Now, in my case, I have to say, I'm no great portrait maker at all through digital imagery. The reason I bring that up, because there's been, through that there's been a huge democratisation of creating a portrait, which I think actually sharpens our judgments about what is a good portrait and not such a good portrait and also makes us think hard about, and rightly so, about who should be in a portrait gallery, because just as you were describing earlier, and I think, you know, the door's are open and it shouldn't, the portrait gallery should mirror all of society if at all possible. That's utterly different to the late 19th century sort of model that we've grown away from.

Hmm. Did you want to comment on that, Paul?

Yeah, I mean, there's a lot to, there's a lot there. I think, I mean, I know that at the New Zealand Portrait Gallery, we were very interested in trying to make our collection more representative of the nation in every kind of respect. And one of the things that's kind of remarkable is it's a, a gallery is very, has a small collection and it's not a very old collection, but it's still a collection that has exactly the same kinds of biases as you would see in a collection 200 years old. I think we have maybe one portrait by a woman in our entire collection, things like this, and we don't really collect, is the thing, anymore. So it's, we, I think we kind of work to open up different possibilities for what a portrait gallery can be through our kind of exhibition program of loan exhibitions essentially. All of our exhibitions basically are built around loans almost entirely. Yeah.

Mm. And would you say that your institutions and you as curators, so as representatives of national portrait galleries and as curators of portrait collections, are you, can you tell us about some examples from your own work or from your institution where you think we are, work that you're doing that you think is subverting those sort of conceptions?

And I know Christopher, you had a couple of slides.

Well, one particular example-I really appreciate using in this context to help answer your important question. It's the actual, "Brain of the Artist." That's the title, it's glass.

Yeah. That's a fantastic work

And that's a sculpture. If we could look at that and if I could just take a moment to explain what this is and how it relates to the questions you've asked. So this is work acquired in the last 10 years by an artist called Angela Palmer who was born in Aberdeen, in Scotland and she works in different media. And what you're looking at here is a glass sculpture which consists of a series of sheets of glass that have been very delicately engraved and lit from below and extraordinarily, this is a representation of a scan of the artist's own brain, okay. And it's a very strange, rather haunting and most unusual form of self portraiture. That's why I think it's interesting here, because we're so used to, if I may put it like this, reading people's faces in order to, you know, engage with them, but here we've got a fundamental image about this person's, this artist's sort of specific characteristics, and it throws up lots of fascinating questions about identity, and indeed, whether this is a portrait as we would normally describe it. And, when we acquired this, it, we really didn't know what the impact would be. It's very, sometimes quite hard to judge, you know, how visitors and audiences will react. And in Scotland, the response was overwhelmingly positive. Begged lots of questions. People were fascinated. They were, there was a lot of discussions going on around it, as you might imagine, which is very pleasing, but it also bridged different audiences and perhaps this is obvious, but we hadn't anticipated it. Not only where lots of gallery visitors really interested, but it engaged the scientific community too because of its nature. And it's slightly hard to describe. I want you all please to come and see it in person. It's like one of those, it's one of those objects that really is not well served by reproduction. In fact, having spoken a lot about how things are reproduced, but it's strangely tremulously beautiful actually, but it takes that the whole idea of portraiture and what portraiture is and the power of portraiture offered a completely different direction from what most of our collection suggest to people.

Mm. And I love the way, well, for me, I mean one of the things that really resonates with me about that work is it's situation in Edinburgh, which was the sort of cradle of medical teaching for 18th and 19th century, so it's got this wonderful sort of conversation, it's in wonderful conversation with its location and with your beautiful 19th century building. And I remember when I last visited the NPG in Edinburgh being very envious of that wonderful sort of room that you have with all of that fantastic collection of death masks, which I was very covetous of, I must say.

Well, you're looking there at the, thank you for bringing up that slide, 'cause that's the gallery, it's a sort of palace of art is probably the way to describe it, very much in 19th century taste. And you can see the great hall of the gallery. I hope that everyone would see that. Now "The Brain of the Artist" which we were just looking at, when we first displayed it we put it right in the middle of that hall and it was sensational, having the contrast between this very impressive, but very traditional setting and a radical and thought provoking portrait, and self portrait in this case, in the middle of it. May I just pick on something you said? You mentioned about conversations and resonance and it's absolutely I think key in the moment, that's it seems to us that portrays are powerful when they get people talking, they get, it's that engagement and that challenge that really is a measure I suppose, of whether we're doing our work well or not, in fact, actually, as curators really.

And there was another one of your slides, I think Christopher, that you sort of have discussed in that context that the portrait of the three oncologists by Ken Currie.

Yeah, could we just very briefly show, this is a--

Yeah, that's a wonderful painting.

It is an amazing painting. It's a large oil painting, this, and it shows just as you say, three oncologists, three very distinguished experts who are engaged with the fight against cancer. It was actually thee, when this was painted some, few years back now, they were all working in Dundee, very distinguished centre for research and it is an extraordinary painting. It's a very powerful, very, I have to say, very disturbing painting. I mean, it disturbs me every time I see it but once you know a little more about how and why it was created, it has proved to be very, very inspiring in fact, for many people who've come to see it. So the three men who you see here, they've just been engaged with a procedure, and they are literally rapidly moving away from it because they want to go and share everything that they've learned with other colleagues across the UK and around the world. They are engaged in the highest levels of research and this incredibly important fight against this devastating disease. And it's a painting that's become again, an overused term, but it's become a bit of an icon for our collection because so people remember it, the sort of ghostly figures emerging from a dark background, but we've also had so many people who've wanted to come and see it because their lives have been touched by this terrible disease. And actually they, I know, because I've spoken to a number of people, there's a different type of power here we're talking about. But for a number of people, that's personally very powerful for them and I suppose reassuring, that's a very simple description, but it means that it's great to be reassured that such brilliant people, such great brains, are engaged in this very important fight. So that's a very different type of power from portraiture to the sort we've been looking at earlier on, a very personal, very, very modern as well I think actually.

Yeah, and I've just got an alarming message on my screen saying that we've only got about 10 minutes to go, and I know Paul, you've also been working on yet another really interesting exhibition, which I wish I have could have got to Wellington to see. And that was an exhibition based on a works from the collection of the Alexander Turnbull Library in Wellington and it was an exhibition sort of looking at the relevance, the contemporary relevance of historical portraiture, and I know in the slides that you sent through there were some fantastic images to discuss, and I'm particularly intrigued by all of those variations on the Tupaia drawing of Joseph Banks with the lobster. Could you tell us a little bit of those in the context of that exhibition?

Absolutely. So maybe we can get the original drawing, yeah. So this drawing is in the British Library. It's not here in New Zealand for us to put on show, but it's an image by this guy, Tupaia, who served as, he was from the place we now call Tahiti and he was the navigator for James Cook on one of his trips down into the Pacific and this is a drawing he did, and it's a drawing we think that the European man is Joseph Banks and we don't really have an idea of who this Maori man is, but it's a really interesting example of a very early kind of portrait almost and the kind of Western tradition of portraiture of these two individuals, even if we can't identify who they are, and it's an item that's proved very resonant for contemporary artists in New Zealand. That's one of the sort of earliest surviving depictions of a Maori person and it's sort of significant because it was drawn by another person who was Pacific, not a European. It's not one of these kinds of ethnographic depictions.

Which so many of the images from Cook's voyages were.

Exactly. I mean, we can, if we can bring up the first two, the "Man of Easter Island" and "Man of New Zealand," those are perfect examples of those. You know, these people called Man of Easter Island Man of New Zealand. This is just kind of, they stand for a type and "Men of New Zealand," for example we know exactly where he was from. We know what his name was. And I can't remember those details off the top of my head, but he, this is a depiction of a real person, a specific real person, but he's called Man of New Zealand. Anyway, so this picture by Tupaia has been really resonant for New Zealand artists. And I feel like there's a, you know, a potential exhibition just of these. It'd be really interesting to see. So there's exactly, this is by a painter called Ayesha Green and this is a huge work. This is, this tiny little drawing blown up to be I think two meters tall and three meters wide and Ayesha's like characteristic style is to like flatten the thing she depicts and you kind of lose that in this one, because the original she's working from is flattened itself. But Ayesha I think, Ayesha is a Maori artist herself. And I think she's really interested in thinking about colonial encounters and representing them in her practice. Anyway, so the other, if we can show the embroidery now, this is one we actually showed at our gallery, and Sarah Munro actually like replicates this image serially. She's done about 30 of these embroideries, and they all centre on these two figures and she kind of changes the objects that they're exchanging to kind of comment on New Zealand's kind of ecosystem, largely, the effects of the colonial encounter on our wildlife. So you see here, the Maori figure has birds and the European figure has cats and possums and weasels that are kind of a threat to these animals, to these birds. Anyway, so like what we were interested in doing in this exhibition, and this work by Sarah Munro is part of it, we're interested in thinking about how historical portraiture can be a source for people to, for artists to react to and reinterpret the past and make sense of it in different ways.

Yeah.

Yeah.

If we've got time, can we just quickly have, while we're on the subject of Joseph Banks, could we have a look, firstly, a very very different representation of Banks. That's a mezzotint after a painting by Benjamin West. So it's Bank with his, he's got a buck cloth cloak and all of his booty that he collected on the end of a voyage.

Yes, there we are. So this is a mezzotint from our collection. The original painting is in the Usher gallery in Lincolnshire in the UK. Banks, of course, he was painted famously, painted twice for the 1773 Royal Academy exhibition. The very famous painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds which is at NPG London and a painting by Benjamin West of which this is a print. So it's, you know, I don't like using the word iconic, but it is kind of an iconic representation of Banks. And very much speaks to that sort of, you know, devil may care kind of looting attitude that he took towards his voyage on the Endeavour. For him, it was, you know, it was very much an adventure. He sort of dressed it up as science, but, you know, it was also, you know, he famously said, of course, that he wasn't going to do the grand tour of Europe because every blockhead does that. His grand tour was going to be a tour around the whole world. But this is a, I think a really sort of fantastic example of what you were talking about, Paul, about how even, you know, on the face of it, something which is historical and problematic can actually be utilised and subverted in really creative ways by contemporary artists. And if we go to the next slide along, Robert, we'll see this image by an indigenous Australian artist named Daniel Boyd. He's from the Queensland area and it's part of a series, so there's this kind of subversion of West's painting of Banks. There's a similar one, which is at the national gallery actually, which is where he's kind of subverting James Weber's portrait of James Cook, John Weber's portrait of James Cook, which is in our collection, and there's also a painting of King George III, I think he's done a take on Nathaniel Dance's painting of George III, but on the face of it, this is, you know, this is a parody, but it's also an incredibly rich and powerful and incisive kind of critique of the behaviour that Joseph Banks was engaged in. And you'll see, just sort of near his foot there, his left foot, there's a, it's actually a self portrait by the artist and that's actually, it's referencing Joseph Bank's souveniring the head of a Darug warrior named Pemulwuy and, you know, souveniring that and sending it back to England to be housed in a collection somewhere. So it's actually, like I say, a very sort of powerful critique of, you know, these colonial, these tremendously awful colonial practices, but how contemporary artists can manage to at least, you know, reclaim some of that imagery and sort of twist it to their own ends and subvert what would otherwise have been a very sort of powerful representation of a powerful white figure. Does this mean we're out of time? I'm sorry. There was actually one question for you, Paul, which I think will answer very quickly. A question from Jennifer who wants to know if you could explain what you meant when you said that the Portrait Gallery of New Zealand doesn't collect, is that a budget factor or is it?

So it's two fold. In the one hand, it's a budget thing. We don't really, we operate entirely on a donations basis. So we don't have a huge budget. And the other thing is that we also don't have much space. Our collection store is pretty much full. If we get anything new, we'll have to get rid of something we have.

It sounds like my wardrobe. Well, yeah, I'm terribly sorry, but I'm afraid I've waffled on too long and we have gone over time. But before I hand back to Gill, I just wanted to thank you both. Maybe we should have a round two. There's obviously a lot of fruit in this discussion. So it's been really lovely to speak to you this evening, and this morning in your case, Christopher, and thanks so much for agreeing to be part of 15 Minutes of Frame.

Thank you.

Thank you. It's been a pleasure, so thank you.

Thank you so much, Christopher, Paul, and Jo, I could've listened to that all night. Honestly, when Jo said, perhaps we should do a part two I think you took the words right out of my mouth. Might be a part three and part four, a can of worms has turned into a cabin. But yes, thank you so much for such a really interesting discussion about power and portraiture. Thank you everybody who joined in here on Zoom and also live on Facebook. We run these 15 Minutes of Frame quite frequently and we have another one coming up shortly. So please jump on our website, portrait.gov.au to get all the latest information. It's always great if you sign up for our emails or follow us on socials at portraitau, that way you won't miss out on anything that's coming down the pipeline. Thanks again, everyone for joining us from all over the world and we look forward to seeing you again soon.