Luke Cornish, aka E.L.K. describes his street art and portraiture

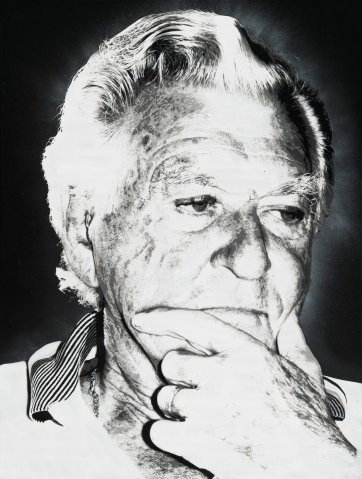

- I'd had the influence from my grandmother who was an artist. She always gave us activities to do, so. From a very early age, I was making art. And I think that sort of carried on into my teens. It was always a hobby, something I did in my spare time. And I think when I got to my twenties, maybe, I started making art more and more. And eventually, it just kind of got to the point where I didn't have to go into work anymore 'cause I was making enough money from my paintings. Growing up in Canberra and being politically motivated, I started doing single land political stencils on the street. And, which became a bit frustrating over time because you put all this effort into an artwork to have it painted over by the council the next day. And I think that really... really made me decide to have more of a studio-based practise where I could refine my craft and evolve my technique, and sort of push the limits of stencil art further than just a one layered stencil and something to a photo realistic image. So that was kind of the motivation behind that. Bob Hawke was the first portrait I painted after Father Bob. I think I'd sort of... Tried very hard to make it as perfect as possible. There's about eight layers in it, done in three sections. So the top, the middle, and the bottom, sort of put together like a jigsaw. I picked Bob Hawke. It's my grandfather, actually. They were born on the same day and my grandfather had a copy of the Bob Hawke biography that was signed to him from Bob Hawke like, "Happy Birthday for the day." And I took it back to Bob 30 years after when I had a sitting with him and got him to sign it for me too. 'Cause that's the only thing I've gotten from my grandfather after he passed away. It was a strange experience 'cause I kind of got this sense from him when I was there. It was like, hurry up and get the fuck out. Like I didn't, I did not have time for this. But when I'd sort of taken the time to explain why it meant so much for me to be there and to be painting his portrait, he really kind of warmed to me after that. It was really nice after that. So yeah, it's kind of, it's got a huge sense of mental attachment to that portrait. I didn't wanna go for the Aussie larrikin 'cause I didn't feel like that's who he was. When I moved to Sydney, I moved into a studio in Summer Hill and this guy was running and sort of had him into the studio. I was telling him about my portrait of Bob Hawke and he was saying, "Oh, what's Bob Hawke like?" I can't remember what I said, but this guy turns out to be Bob Hawke's stepson and we're still very good friends 10 years later. So I must have said something good. Obviously I would've. The portrait of Bob Hawke took about three to four weeks. And that wasn't, like, three to four weeks of working every little bit here and there. That was a solid 12 hours a day, seven days a week doing it I think to a deadline to enter it into the Moran. Yeah, I think I burnt myself out on that one. It was a big job. And the first time I ever even entered the Archibald, I got in. But it wasn't so much getting in, it was just the field day that the media had. It was crazy. Like it was the front page of every newspaper in the country and like, it was the, my face was the header of news.com for 24 hours. Like, it was just literally trending. And it was really overwhelming. Like sort of having gone from no exposure whatsoever to just this massive amount of exposure. It was quite, yeah, it was quite terrifying actually. I wasn't ready for that. I think I had success long before I was actually ready for success. But you kind of roll with it, especially in the Salon. Like, I love getting into the Salon as a street artist because the whole ethos of that award is the refused, the rejected paintings coming, dating back from the 1900s with the Impressionists. Yeah, it's... I think I just entered the Archibald just to get into the Salon. I'm always happy to get into that award.

Related people

Related information

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

Support your Portrait Gallery

We depend on your support to keep creating our programs, exhibitions, publications and building the amazing portrait collection!

Plan your visit

Information on location, accessibility and amenities.