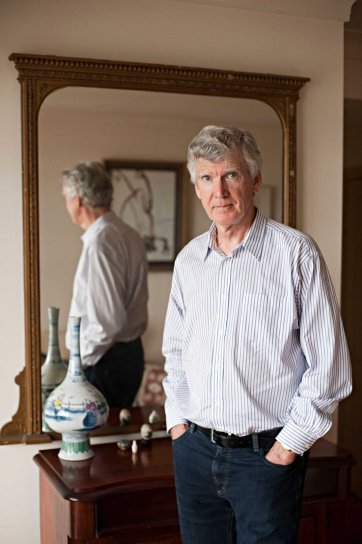

Australian playwright, David Williamson tells us tales from his career.

- I always wanted to tell stories for some reason, I don't know. When I was young, I started scribbling stories that were highly derivative of the kids books I was reading. There was no originality whatsoever, but I did want to tell the stories. I don't know why. Then I was good at maths, unfortunately, and I was told that all boys who were good at maths did science, did engineering or did medicine. And I hated the sight of blood, and I hated chemistry and mechanical engineering was the least chemistry of any maths course. So I did it without being the slightest bit interested. But I finished it because my father said, you've got to have something to fall back on, like qualifications. But then I went back to Melbourne University, ended up taking preliminary psychology because that's what human motives and what made humans tick was my obsession at that stage. That's what I really wanted to know. I was at a play, a Melbourne Theatre Company early play, and suddenly a voice in my head, and I'm not schizophrenic, but a voice in my head said, "That's what you should be doing." So boom, I'm gonna write plays. But at that stage, it was very difficult to get an Australian play on stage. It was our theatre companies, Melbourne Theatre Company, that were controlled by Englishman who saw their function as educating and uplifting the barbarous natives by the finer aspects of European culture. But I got my chance when the small theatres sprung up around Carlton, and they did my first play, full length play, "The Coming of Stork." And then "The Removalists," which really clicked. I love having to create something that was going to hopefully work in front of an audience. The big buzz of being a playwright, as a distinct from a novelist where you might see someone reading your book on a train once every three years, when you're a playwright, you actually get the sense of an audience reacting to your play right there and then. It's exciting, and I knew that right from my review days. We'd had a big hit with "The Club," and Frank Wilson, the actor was, was brilliant in it. And Rodney Fisher, my director at the time said, "Write another thing for Frank Wilson. Write a comedy." And I did bad farces about old guys, and it wasn't working. And Kristin's mother was living with this, and her life story was fascinating because years before, I'd gone up to New South Wales coast and met Kristin's mother who was married to an older guy who was an incredible character called Wilkie. He was an ex, he was an electrical engineer, an ex communist who'd stood as a candidate in the Seat of Toorak, which was clearly was not going to work for him. But he was opinionated. He was acerbic. He was intelligent. And suddenly Frank Wilson and Wilkie fused in my mind. And I said, there's the play. And I went to Kristin's mother and said, "Do you mind if I sort of borrow your story?" And she was very gracious. And she actually gave me the diaries that he, that he wrote, and they weren't much diaries, but he was obsessive. So every time they set out on a journey in the car he'd write a list of all mosquito coils, torch, medicines. And I reproduced that list exactly in the play as they're setting out for one of their journeys in "Travelling North." And the filming of Travelling North was fabulous because we had Leo McKern, Graham Kennedy and Henry Szeps, three of the funniest guys and greatest actors you'd ever see. And I came up on the set, and I was allowed on the set that time, and they had a day off, and we all went out to the reef to see the Great Barrier Reef. And they were great guys, but they were all competitive. They all had to be funnier than the other one. So the three of them, it was the greatest comedic show I ever saw. I was sitting opposite them, and they were outdoing each other with anecdotes. And Leo McKern finally got fed up, and he pulled the best trick of all. He just took his false eye out and put it on the bench, and before he went snorkelling said, "Keep an eye on me." And that sort of won the day.

Related people

Related information

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

Support your Portrait Gallery

We depend on your support to keep creating our programs, exhibitions, publications and building the amazing portrait collection!

Plan your visit

Information on location, accessibility and amenities.