When he came to Australia in 1850 William Strutt was the best trained artist so far to arrive in the colonies. Moreover, he was the only artist in Victoria with a strong sense of the way in which contemporary events become the stuff of history. He made sure he was present with his sketchbook when anything of historical moment was to be recorded including the Victorian Exploring Expedition led by Burke and Wills. He was present at the departure of the expedition from Royal Park on the 20th of August. And it is remarkable, that on the day of the departure, Strutt had the foresight to team up with a photographer. The photographer snapped Burke giving his brief farewell speech to the Mayor of Melbourne. When the artist was commissioned to paint a posthumous portrait of Burke, he used the photograph to get Burke's pose, a pose later described as 'thoroughly characteristic of the man'.

When it was completed in January 1862, Strutt's portrait was recognised as a fine work of art, both as a likeness and a depiction of character. The Argus could not help finding evidence of tragedy in the portrait, commenting that Burke's 'fiery outlook is slightly dashed with melancholy, as though he were forecasting some peril, or speculating upon some possible disaster and the whole countenance wears a thoughtful but determined expression'. The journalist concluded that there had been 'no attempt to idealise the subject. Burke stands before the spectator just as he lived'.

We are accustomed to thinking of posthumous portraits as not quite as authentic as those painted from life and for the most part they are not. Yet Strutt had excellent material - drawings and photographs - to combine with his first-hand knowledge of the man and was able to impress the features with character There is at least one other great example of such a convincing posthumous likeness - John Webber's 1782 portrait of Captain Cook, that hangs in pride of place at the National Portrait Gallery. The artist of this sweeping and entirely convincing portrait, Burke addresses the Mayor of Melbourne on the day of the departure of the expedition, 20 August 1860 photographer unknown Dixson Library, State Library of New South Wales John Webber, was with Cook on his last voyage. He had years of close observation of the man and had painted Cook from life at least twice before he was killed in Hawaii in 1779.

There was a sad coda to the completion of William Strutt's portrait of Burke. On the day after the unveiling of the portrait, Strutt left Melbourne to return to England. The Argus commented that 'the colony will lose an artist whose abilities have been scantily rewarded and imperfectly appreciated in Australia'. The imperfect appreciation that Strutt felt most keenly was the failure of the men of the day to get behind his plans to celebrate, for posterity, the independence and development of Victoria. He had sought subscribers to fund paintings of the opening of the first legislative council and the first meeting of the Legislative Assembly in the new buildings in 1856 - a 'brilliant scene' as he described it - yet both projects foundered through what he described as indifference.

There is an echo of Strutt's attempts to persuade the government leaders of his day to take some interest in the historical record in 1910 when Tom Roberts, like Strutt before him, a fine portraitist with an eye to posterity, attempted to convince Prime Minister Alfred Deakin to begin a program of official portraiture. Roberts wrote that it disturbed him to think the politicians of earliest federal parliaments were likely 'to leave behind nothing that will give the future anything that will show what you all were as men to look at'. Roberts asked Deakin; 'What would America give for authentic records of its founders?'

That question pointed forward to the idea of a National Portrait Gallery. Roberts felt that it was 'the duty of the present to the future' to create an official portrait record of Australia. And his ideas were taken up. In 1911 the Historic Memorials Committee was established to commission portraits of prime ministers, governors-general and chief justices. Briefly the Committee toyed with forming a National Portrait Gallery by listing famous Australians or historically significant figures connected with Australia. A couple of portraits were painted from nineteenth-century engravings, but the very idea of painting, say, Matthew Flinders, over one hundred years after his death, missed entirely the sense of authenticity which is at the heart of the idea of all national portrait galleries.

When the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra began building a collection in 1998, the ideas of historical importance and historical authenticity, (cornerstones of the National Portrait Gallery in London), were key criteria for the inclusion of portraits. That great Victorian-age institution - the National Portrait Gallery in London - has provided many precedents for the Canberra Gallery. It also provided the strongest impetus for the foundation of the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra. Gordon and Marilyn Darling, the most committed believers in the idea of an Australian Portrait Gallery, and who finally transformed all of the talk that had been going on about such a Gallery since the 1860s into a solid reality, were able to point to the popularity and the success of the London model in promoting the idea of an antipodean counterpart - a Gallery in which Australian achievement, character and national identity could be seen and celebrated.

Historical authenticity is one aspect of the portraits included in a National Portrait Gallery. It is usually easy to establish the authenticity of a portrait. I am often asked, though, what is it that makes a good portrait? The answer is that a portrait must be faithful to the person represented and to be sufficiently good as a work of art to convey a sense of that person to the viewer. 'Is there a real person in there?' is a question we ask when looking at any portrait. A likeness is fundamental, but likeness is not easy to define. At is best the art of portraiture all about conveying vitality.

Of course the ideal in a National Portrait Gallery is always to have an important subject portrayed by the best possible artist. Where such combinations exist the results are usually of the greatest interest.

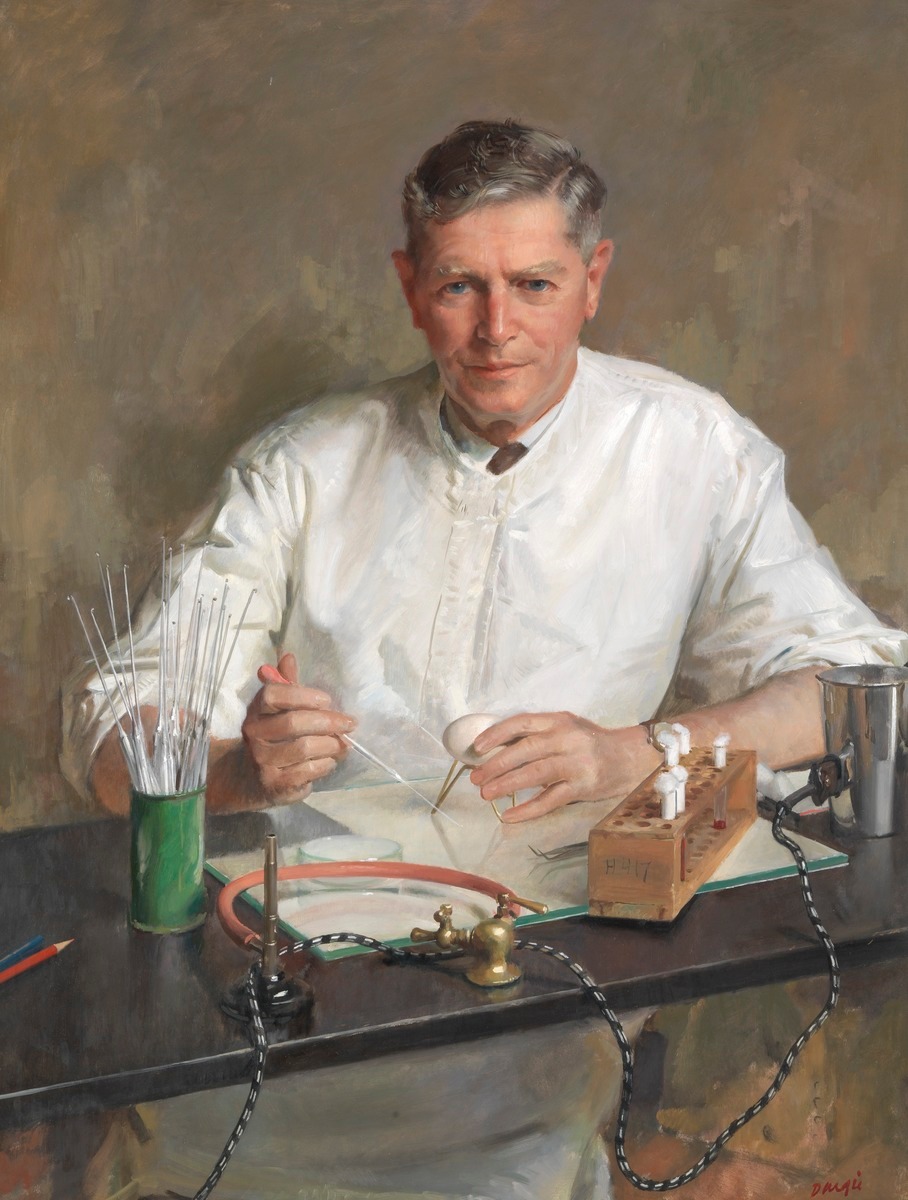

Webber's portrait of Cook is one such example of an immensely important figure painted by a fine artist. An example from a more recent time is the late Sir William Dargie's portrait of Sir Macfarlane Burnet. This portrait, which Dargie considered one of his best, was painted the year after Burnet had been awarded the Nobel Prize. Those who knew the subject attest to its vividness - the quality of accuracy in that direct, straightforward look. And there is the added dimension of the paraphenalia of the scientist - the tin cans painted with green enamel that held the pipettes, the egg being inoculated with a culture, the jug holding the hot wax that sealed the eggshell. Where he could Dargie liked to add things to create interest in his portraits - Albert Namatjira, the subject of an unusual profile portrait is seen clutching one of his watercolours - and his splendid likeness of Margaret Court, painted at the height of her career, includes a clutch of beautifully painted tennis racquets.

A no less vivid portrait and striking likeness is that commissioned by the National Portrait Gallery of the Nobel laureate Peter Doherty. Rick Amor's portrait of Doherty is not crowded with lab equipment - largely because at the time his portrait was painted (on one of the scientist's return visits to Melbourne from the base in Memphis) the subject saw himself as more of an administrator, an advocate for science, rather than a hands-on researcher.

There is no doubt that portraits which include deeper levels of meaning add life to a National Portrait Gallery. Some of the Gallery's most successful commissions have been those that have embodied such deep levels of association. An extremely popular portrait is the Victorian Tapestry Workshop's beautifully woven portrait of Dame Elisabeth Murdoch; it includes references to two of the subject's major devotions - to her garden and to the tapestry workshop of which she is the enthusiastic patron.

In addition to many paintings and works in tapestry and drawings, the Gallery has also commissioned photographs. This has raised the inevitable questions about the validity of photography as a medium of portraiture. In the mid 19th-century, during the very earliest years after the development of photographic processes, there was already something of a prejudice against the use of photography in portraiture. Here there is an interesting note in the case of the picture with which I began: while newspaper reports about the portrait mentioned that Strutt had been with Burke on the day before the expedition's departure, there was no mention of the fact that the artist had based the head and shoulders in painting on a photograph - Thomas Hill's portrait of the explorer, made before the beginning of the expedition.

At the beginning of the 21st century, I think it is important that we acknowledge the importance of photography as a medium of portraiture. Photographs can do things paintings cannot do and vice versa.

Contemporary explorer, Australian astronaut Andy Thomas, was photographed for the National Portrait Gallery by the Canadian photographic duo of Denis Montalbetti and Gay Campbell. Just as Strutt had painted Burke in his bush gear with that distinctive hat, it was important to capture Andy Thomas in his astronaut gear. Yet in the wake of September 11, access to the flight suit caused enormous difficulties. Since these million-dollar items do not leave the space centre - except when they are worn into space - the photographers had to shoot the portrait in Houston. It is a portrait that celebrates the man, yet, in a characteristically Australian way, doesn't take itself too seriously. This was a portrait that could only have been made as a photograph.

Similarly David Moore's immortal portrait of Dawn Fraser taken in the lead-up to the Tokyo Olympics: here is a face caught inside a moment; a portrait of the intensity and concentration propelling the swimmer to a single goal, captured in that instant when she looks up at her coach from the pool.

At the National Portrait Gallery we embrace portraits of all types and from the historical to the contemporary. What is unique in the portrait gallery experience is the one-to-one experience of another person. The more vivid the portrait, the more vivid this encounter will be. Regardless of whether they are paintings or photographs or sculptures, the portraits each tell us something about the person and remind us of that individual's place in the shaping of Australia. I think William Strutt and Tom Roberts would be well satisfied that the National Portrait Gallery is at last fulfilling 'the duty of the present to the future'.

Over the past five years our hundreds of thousands of visitors have embraced Australia's National Portrait Gallery and the stories in it. This is because, I think, the Gallery provides a reassuring experience for us as individuals. We all have lives; we have our highs and lows; things we have added to the world; ideas we have wrestled with; people and places we have loved. Regardless of where our lives are lived or have been lived - in Canberra or Cape York, Papunya or Bruny Island, Cooper Creek or Melbourne -the National Portrait Gallery is a gallery for all Australians: it is in a very real sense your Gallery.