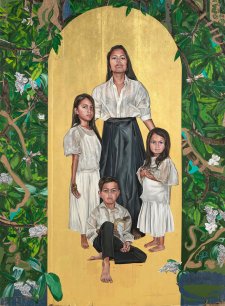

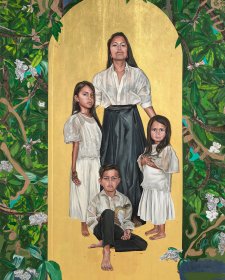

Gunggandji artist Simone Arnol’s deeply personal and evocative series of photographs exemplifies the power of contemporary portraiture to retell and regenerate histories that were deliberately minimised, disregarded and suppressed. Commissioned by the Cairns Art Gallery, seeRED is a heart-wrenching visual and aural testimony to the complex history of Yarrabah and Arnol’s great-grandmother Tottie Joinbee, affectionately known as Granny Tottie, connecting the past with the present and the future.

Located on the lands of the Gunggandji people in coastal Far North Queensland, Yarrabah is a vibrant, cultural place, widely acknowledged as the largest Aboriginal community in Australia. Yet, like much of colonised Australia, Yarrabah holds a complex and tumultuous history of violent displacement and cultural suppression due to missionisation. Operated by the Anglican Church, Yarrabah Mission was established in 1892 under the authority of Ernest Gribble. The history of the mission, which operated until 1960, has often been recounted from a non-Aboriginal perspective, with limited literature that offers true insight into the deeply personal legacies and stories of the early First Nations residents.

In her photographic series, Arnol actively readdresses the colonial narrative. Photography has played a significant role in the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people since its arrival in the 19th century. Its use in documenting, surveilling and controlling First Nations people, while simultaneously reinforcing harmful social ideologies underpinned by scientific racism, resulted in the adoption of widespread national polices of assimilation. The systematic removal of children from their families is a deeply painful and tragic legacy that still permeates modern Australia, where survivors and their descendants seek to reveal the truth and horror in these histories. By reclaiming the photograph, Arnol recentres the Aboriginal experience and honours the lives of those stolen.

Born in around 1899, Tottie was removed to Yarrabah Mission in 1914 under the Industrial and Reformatory Schools Act 1865 after falling pregnant. She was 14. Having lived to the age of 110, she remains a deeply respected woman who held onto her cultural identity and knowledge despite the efforts of colonisation. Following in her great-grandmother’s footsteps, Arnol’s strong connection to family, Country and culture is the foundation for all her art. In her photography practice, she uses powerful narratives to convey the true messages of her history and her people.