It has been joked that Captain Cook discovered Australia, but Barry Humphries rediscovered it. It would seem fitting, then, that the National Portrait Gallery should choose Barry Humphries as the subject of its first biographical exhibition.

With more than three hundred objects in the show, curator Simon Elliott has chosen a few that open up some of the very interesting 'lives' of Barry Humphries.

A prerequisite for any researcher into the life and career of Barry Humphries is a degree of self-control - in particular, the skill of suppressing laughter in quiet research areas of libraries, archives and galleries. It's hard work, because Barry Humphries has built his international reputation on his ability to make people laugh; laugh that is until they fall off their seats!

When most people think of Barry Humphries, their minds turn quickly to his high-profile creation, housewife and megastar Dame Edna Everage of Moonee Ponds. However, Barry's talents are not confined to theatrical caricature. He is also a visual artist, writer, poet, comedian, art collector and social provocateur. Rarely Everage: The Lives of Barry Humphries is the first exhibition about Barry Humphries that attempts to bring all these elements of his life and career together.

I was overjoyed to find this image (facing page) of a wet Barry aged around five in a family album. Barry's father Eric was a very successful house builder, who prospered in the transformation of an old golf course in Camberwell, Melbourne to a 'garden suburb' that offered no quarter for backyard chicken coops or native trees. Barry was the first born in this purposefully pleasant environment. Along with building the family home, Eric Humphries installed (in the early 1940s) one of the suburb's first inground watering systems, and Barry fondly recalls his joy of running in and out of the spray of sprinklers. Eric was clearly proud of both his son and the perfect green grass. So much so, that when war came he chose to build the air raid shelter in the house because he could not bear to ruin the lawn.

Barry was sent to Melbourne Grammar School, where he refused to enjoy sport, avoided cadet corps on the basis of conscientious objection, and graduated with brilliant results in English and Art. He spent 1953 and 1954 as an unenthusiastic Law and Arts student at Melbourne University. Although his academic record at university was woeful, he effortlessly became Australia's leading exponent of the deconstructive and absurd art movement, Dadaism. When his discomfiting jokes incited student audiences to storm the stage, Humphries was introduced to the joys of audience participation.

This drawing by the fourteen-year-old Barry is interesting for a number of reasons. First, it illustrates his early talent for and love of drawing. But it also expresses his early preoccupations with the subtle differences with class, homes and houses and language. His acute ear for the vernacular has been central to his genius. Particularly in the early days, the comic effect of the character Edna was simply achieved by Barry's word-perfect, earnest replication of the speech of a Melbourne housewife. There are fascinating early scripts in the exhibition that show Barry's painstaking corrections and rewriting to ensure the exact words. Over the course of many years however Edna's sensible outfits and shyness covered with her chorus of 'Excuse I' were replaced by lavish costumes and familiarity with international celebrities.

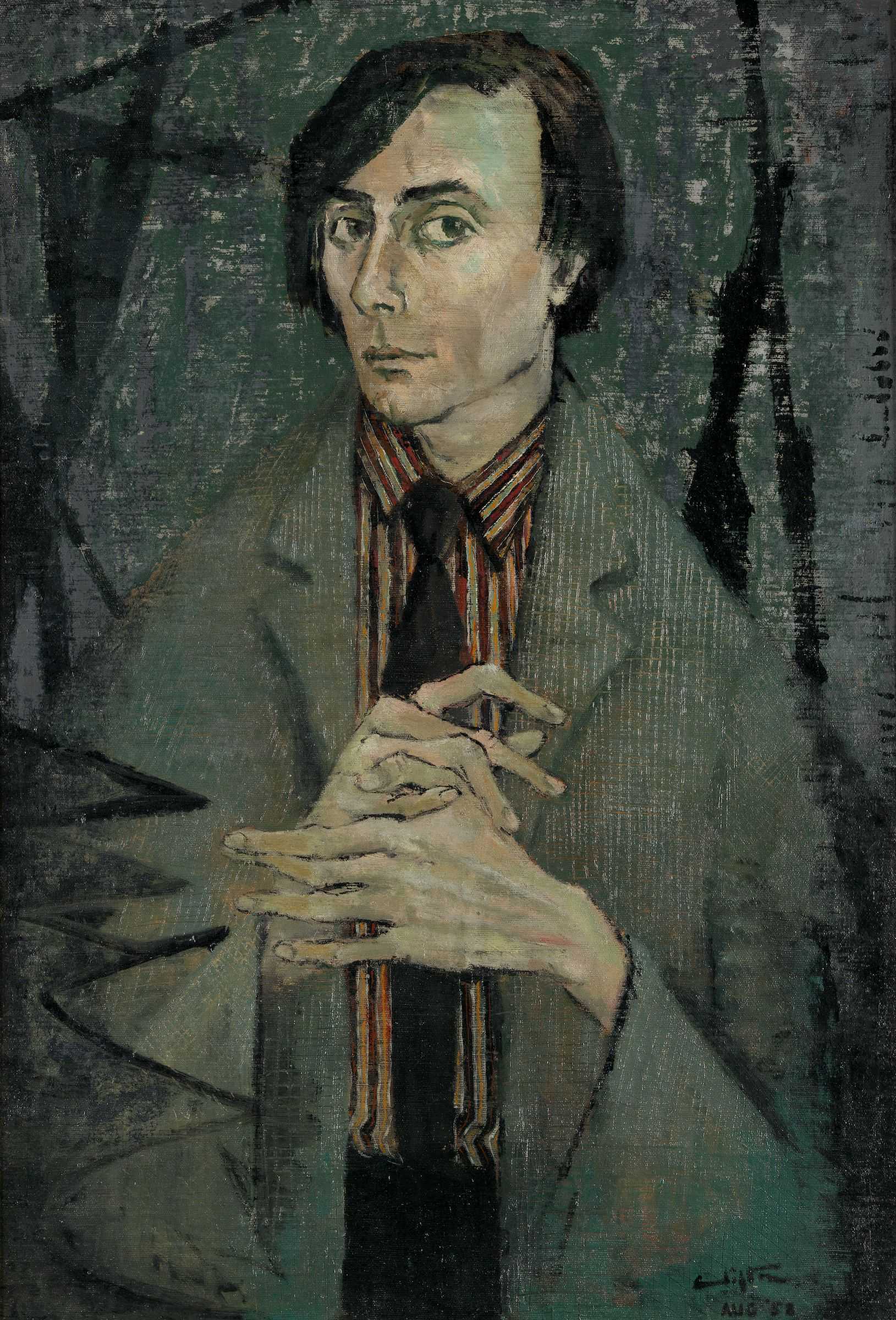

Clifton Pugh's painting of a young Barry Humphries in 1958 was the first work acquired by the National Portrait Gallery. Painted in the years when Barry was a fledgling theatre performer, it shows a pale aesthete with hands like toasting forks. The hands refer to one of Barry's early party turns, a characterisation of a moronic and other-worldly hominoid called Tid, who also occurs in a novella and in sundry drawings by Humphries. Later, Pugh painted a portrait depicting Barry as more worldly and less naive than he appears in this image.

Humphries left Australia for London in 1959, just as his satirical stage work was beginning to gain momentum. Throughout the 1960s he appeared in London theatre productions of Oliver, Maggie May and Treasure Island. In 1963, he was invited to write for the satirical magazine Private Eye. For ten years, with the New Zealand-born cartoonist Nicholas Garland, Humphries produced the Barry McKenzie strip, chronicling the life of the brash Australians that he met so regularly in London. Private Eye was banned in Australia, but the strip led to the film The Adventures of Barry McKenzie, at the time of its release the most successful Australian film ever. This cartoon by Philip Burgoyne shows Humphries and the film's producer, Phillip Adams, growing increasingly desperate in their efforts to cast London-based Australian actors who had not forgotten their Australian diction. Humphries's Barry McKenzie, brilliantly portrayed by Barry Crocker, both revived and invented scores of Australian colloquialisms, most of them describing urination and vomiting.

One of Humphries's three great characterisations, the ghostly returned serviceman Sandy Stone is fated to be overshadowed by the brashness of Edna and vulgarity of Sir Les Patterson. Humphries's ear for particularities of speech is as integral to the success of Sandy as it is to the other characters, but his agonisingly slow delivery and his beguiling gentleness set him apart from all of Humphries's other characters. Interestingly, in 1958 Barry and Peter O'Shaughnessy played opposite each other in the Australian premiere of Samuel Beckett's Waiting for Godot. This was, of course, a watershed. In addition there is a good case for arguing that Barry adapted from Beckett the reduced set, the long pauses and the lack of action for his presentation of Sandy Stone. Sandy is widely considered by drama scholars to be one of the most significant characters in the history of Australian theatre.

Lewis Morley, one of the signature British photographers of the 1960s, first photographed Humphries in London in 1962, around the time of his dispiritingly short-lived season at Peter Cook's Establishment club. He has been photographing Barry ever since, yet despite their long friendship, Lewis he had never 'met' Edna. Accordingly, in 1992, they produced this special homage photograph. It refers to Morley's most famous image, that of a naked Christine Keeler on an Arne Jacobsen chair. But it also reflects the way in which Edna has developed a life independent of her creator. Edna has always instinctively avoided the C-0-M-M-0-N in pursuit of the N-I-C-E, and she does not approve of men dressing up as women for cheap laughs.

A precious gift to Barry from the artist Arthur Boyd reflects his love of painting and landscape. Barry started painting when he was very young, excelling in art at school and under the tutelage of George Bell. But just as he has always been better performing his own material than interpreting that of others, in art he found that he was happiest 'doing his own thing'. Cakes, shoes, forks, pies were the ingredients of his mad Dada works produced in the '50s. However landscape has been a consistent interest for Barry which continues to this day - the Duke of Edinburgh owns one of his paintings.

One of the things I have found most interesting - and inspiring - in putting this exhibition together is Barry's extraordinary perseverance with the characterisation of Edna. It was through the encouragement of theatre colleagues such as Ray Lawler that he appeared on stage as Edna in the first place. In the late 1950s some doubted that she could be understood outside of Melbourne, let alone overseas. Indeed, in 1961 the audience at the Establishment, avid for satire, could only see a hairy-legged young man speaking earnestly of interior decoration. Edna's first success in England was in June 1973 at the Poetry International Festival, but it was another three years before London audiences embraced the character in Housewife-Superstar! This shot shows Edna's preparations for an assault on America following her success in the UK, but the reviews for Barry's 1977 New York show were devastating, and another attempt at America in 1991 fared little better. Finally, in 1999, Dame Edna the Royal Tour ran for ten months on Broadway. Critical accolades for the show notwithstanding, Humphries was warned not to tour the show across the US because it was 'too New York'. He ignored the advice, and toured for a year. As a result of Dame Edna the Royal Tour, Edna - not Barry - was offered an ongoing role in the hit television series Ally McBeal.

Alongside his theatre career of nearly fifty years, Barry Humphries has written many articles and books, including a novel and two autobiographies; made scores of recordings; and written and produced a host of films and television series. Amongst his many awards and honours are the Order of Australia; honorary doctorates from Melbourne and Griffith Universities; the J.R. Ackerley Prize; the Golden Rose of Montreux; a Special Tony Award; a Drama Desk award; and the Outer Critics Circle Award. His Dame Edna is the only solo act to play (and fill) the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, since it opened in 1663. The 1987 show Back With A Vengeance ran for nine months with 100 per cent capacity. I am happy to report that at 68, Barry continues at a cracking pace. He has entertained us with his barbed wit, and provided insights into our culture. But such achievement requires huge energy and commitment which has a human cost. He has lost more than a few friends and a few art works as well as been married four times and successfully overcome alcohol addiction. His castigation of Australian complacency and insularity has brought him into stormy relationships with his homeland. Intimidatingly, he has held true to his hobby of 'baiting humourless and self-seeking republicans'. Working on the Rarely Everage exhibition has been a rare treat and a great insight into an Australian that seemed from the very first day he entered this world, he'd made his mind up that his life was going to be anything but average.