‘I’m not interested in daguerreotypes because it’s an antiquarian process’, said Chuck Close, ‘I like them because from my point of view, photography never got any better than it was in 1840.’ Close has taken and used photographs all his life, working with black and white, colour and Polaroid film, so the question why he would use a near obsolete technology seems a reasonable question.

Of course painting and sculpture, the traditional art mediums, are also technically archaic, but there is the perception that a mechanical medium such as photography is best when upgraded to the latest version, ignoring the unique and old fashioned properties. Just as the slow food movement was a counter to fast food, the idea of slow art offers possibilities. Jewel-like in the metallic sheen of the silver coated plate and the miniature size, Close’s daguerreotypes offer the fundamental detail and intimacy of photography. ‘Photographs are often so big now that twenty or thirty people can view one at the same time, but a daguerreotype is the most intimate image made with a camera, because it is small and only one person can look at it.’

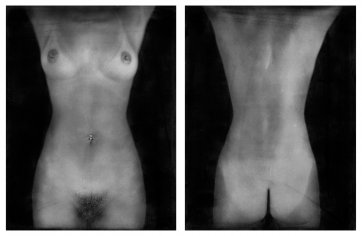

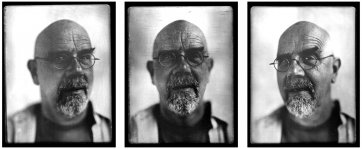

There is some irony in Close reviving the intimate portrait after a life time spent creating imposing billboard sized portrait of friends, who while known in the art world, were not familiar to the average person. Reversing the process he has used the daguerreotype method to make tiny portraits of film star Brad Pitt and of celebrity fashion model Kate Moss. Close’s paintings and daguerreotypes – big and small – are akin to looking down different ends of a telescope. He has always been fascinated by faces, inevitably of friends (in this case artists Elizabeth Murray and Ellen Gallagher) but includes bodies too. Skin, at the scale of his paintings, becomes landscape while the daguerreotypes have the allure and magic of a miniature. Working with Jerry Spagnoli since the nineties, Close has learnt to tailor the process to his liking. He uses the short focal length of the camera to create a shallow depth of field that enhances the three-dimensionality of the sitter’s features. The sheer nakedness of the skin, a feature of Close’s daguerreotypes, is also a factor of process. The original plates were not as sensitive as modern emulsions and exposure was slow, often several minutes long. The process Close uses cuts down the exposure time by increasing the level of light to a critical burst that is so bright it can redden the skin of the sitter and even burn.

Close noted that ‘It was more wartsand- all than any other process. Because it’s so red-sensitive, any marks, any flaws are heightened. You have to be pretty comfortable in your skin, and vanity goes out the window. And it’s also physically painful. A normal daguerreotype is a more than two-minute exposure. We’ve made it instant photography by having a billion foot-candles of light go off all at once, and that’s very painful. The flashes are so intense your eyes slam shut. It’s like having an ice pick shoved in your eyeball. You can smell hair burning… Each one of these people who lent me their image with no control over how it’s going to come out, in this act of incredible generosity, had to put away whatever self-image they had of how they looked and accept this other image as being them. That goes beyond generosity.’

The selective focus, which emphasizes the wealth of absolute detail, has an uncanny effect, as areas of the face emerge into relief from deep background fog. The scale, detail and effort needed to see the image produces an intimacy as personal as reading a book with a similar, one to one, tactility. Daguerreotypes are by definition unique. Not something that can be duplicated and passed around on the web, they adhere to the cult of the original. Theorists like Jaron Lanier and Dr Stan Liebowitz, once champions of the notion that information should be free and of the benefits in sharing, are now suggesting otherwise. Uniqueness and materiality remain valued, especially in the digital age. More than just a print, Close’s use of what might now be termed post-industrial craft has produced a singular photographic object.