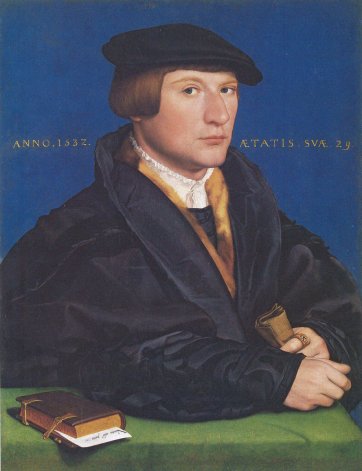

In the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, there is a large portrait by Hans Holbein of the merchant Georg Gisze of Danzig, painted in London in 1532. Both Germans were in England to make their fortunes.

Gisze was based at the Steelyard, the Thames-side depot of the Hanseatic trade: by painting him on an impressive scale wearing his finest clothes and surrounded by the executive toys of the day, Holbein hoped to attract further commissions from Gisze’s fellow merchants. Sadly, the painting on panel is too fragile to travel to London for Tate Britain’s Holbein in England exhibition. Other key works are missing: the portrait of the artist’s friend, the court astronomer Nikolaus Kratzer, in the Louvre. Paintings of Thomas More and his nemesis, Thomas Cromwell, must remain in New York at The Frick, which never lends. Even The Ambassadors is too unstable to move from the National Gallery.

Although their absence is explicable, these works would have greatly added to an appreciation of the roots of Holbein’s art and the circles in which he moved. He was born in the imperial city of Augsburg in 1497/8, the son of a successful painter of the same name. In a fertile urban culture fostered by the new medium of printing, leading artisans flourished, gaining economic and social power. Painters had assimilated the skills of fifteenth-century Flemish artists, enabling them to imitate nature with uncanny verisimilitude. The science of perspective, brought by Dürer from Italy, encouraged them to create more sophisticated optical illusions with the help of lenses and scientific instruments. Holbein was keen to demonstrate such technical know-how in his art. The Gisze painting is a feast of trompe-l’oeil effects, from the unevenly suspended balance behind the sitter to the exquisite glass vase of carnations on the Turkey table carpet before him. Kratzer is portrayed holding dividers and a polyhedral dial, surrounded by other instruments of measurement. The two French ambassadors, Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve, stand in front of a table loaded with the paraphernalia of learning related to astronomy, geography and horology, while stretching diagonally across the floor at their feet is an anamorphic skull, an optical trick which can only be read coherently when viewed from the right. Above all, Holbein’s comprehension of the human face, expressed with a wonderful clarity of line, surely relied in part on optical tools – a convex lens or mirror – which subtly enlarged key features, bringing the individual closer to the picture surface, and to us.

Having settled in Basel in 1515, the artist was employed mainly on altarpieces, stained glass and mural decorations. But the three portraits he painted in 1523 of another Basel immigrant, the humanist scholar Desiderius Erasmus, secured an introduction to Sir Thomas More in London. More welcomed Holbein’s arrival three years later and commissioned a large-scale family portrait, now known only through a compositional drawing (sent to Erasmus) and studies of the sitters. The Archbishop of Canterbury, William Warham, also had his portrait painted as a gift for Erasmus, in return for the portrait Erasmus had sent him. Holbein’s extraordinary capacity to mirror the surface of nature was further displayed in portraits of the Norfolk gentry, among them the lady with a squirrel and a starling, acquired by the National Gallery in 1992.

The artist’s familiarity with the latest fashions in decoration secured an entrée to the court of Henry VIII, who was determined to prove he was thoroughly au fait with Renaissance culture. Holbein produced a battle scene and a cosmic ceiling for Greenwich Palace, where the king was to entertain Francis I of France. His portraits of Sir Henry and Lady Guildford presumably arose out of the commission, for Sir Henry, as Comptroller of the Household, was in charge of the festivities. In 1528, Holbein returned to Basel so as not to forfeit his citizenship, but in the wake of iconoclastic riots and the continuing unrest associated with the Reformation he was back in England by 1531 to pursue his connections with the court and City, perhaps unaware that the political and religious climate was also changing in London.

He found himself painting not only portraits of Hanseatic merchants and murals for their dining hall, but in 1533, their triumphal arch on the theme of Apollo and the muses for the coronation procession of Anne Boleyn, which progressed from the Tower to Westminster. Notoriously tricky, the new queen grumbled that the imperial eagle of the Holy Roman Empire (to which the German Hansa cities owed allegiance) dominated the king’s arms and her own, but the slight does not seem to have hindered Holbein’s prospects at court. As all-round designer on a salary of £30 per annum, he turned his hand to pendants, hat badges and sword hilts, cups, salts and table fountains, even a chimneypiece, as well as a large-scale mural of the Tudor dynasty for Whitehall Palace. At the same time, courtiers and office holders vied for his portraits, to mark a betrothal, promotion or perhaps anxious to secure some form of permanence amid the treacherously shifting affiliations of the times.

In 1538–9, Holbein was sent to the Continent to paint prospective brides for the King, taking the opportunity en route to impress Basel with his new-found prosperity. Christina of Denmark, the recently widowed Duchess of Milan, granted the artist a three-hour sitting and the resulting full-length portrait so pleased Henry that he kept it despite her prudent rejection of his proposal. Even the failure of Anne of Cleves, in the flesh, to live up to her portrait did not curtail the artist’s career. Perhaps his New Year’s gift to the king in 1539, a delightful portrait of the infant Prince Edward holding his rattle like a sceptre, persuaded Henry to overlook the gaffe. Holbein’s ascendancy was short lived, for he died of the plague in 1543. Yet despite his early death and the subsequent loss of major works, he defined the images of a cast of characters so clearly that we cannot envisage our history without them.