I have always liked portraits. They are a microcosm of the huge world of painting, containing its vocabulary in an economical way. Pose. Colour. Gesture. Composition. Tone. Using these elements, they attempt to speak about character, conviction or lifestyle.

Self-portraits are an extension of this interest. Like gallery visitors everywhere, I study the images artists make of themselves, interested in faces and places behind their work, for an artist’s studio is a private space, a site of creativity where most mortals have no access.

Self-portraits are not innocent transcriptions of what the artist sees in the mirror: they are self dramatisations. Like autobiography, self-portraits attempt to tell a coherent story – not the truth, but a truth. Like writers, artists construct, create and present and it is this artifice I like about self-portraiture. Because if images are constructed, then it is possible to deconstruct them to see how artists achieve their effects.

Female self-portraits are a subgroup within self-portraiture. My relationship with them is a story of passion. It began innocently enough with my noting a few famous female self-portraits of the past: Artemisia Gentileschi’s self-portrait of 1630 as la Pittura, the personification of painting, in the collection of H.M. the Queen; Laura Knight’s huge self-portrait of 1913 in London’s National Portrait Gallery; and the 1715 self-portrait by the pastellist Rosalba Carriera which generously includes a portrait of the sister who helped prepare her canvases. Generous, but also professionally astute, since it presents the viewer with a double opportunity to assess her skill at portraiture.

Before I knew it, I had become obsessed, stowing xeroxes and postcards away in a drawer. Secretly I would pursue my passion, sitting on the floor of the Tate Gallery library, not the respectable open reading area, but downstairs where the catalogues are stacked. Sometimes I would be rewarded with a mention of a self-portrait by a woman artist. Or, jackpot, a reproduction.

I even had that disorienting moment when I wondered if my subject was worthy of my passion. After months of collection, I spread the images on the floor. A troubling number of works seemed unexciting, all too vulnerable to the traditional prejudice that female self-portraiture was no more than an extension of the medieval convention of personifying Vanity as a woman with a mirror. Could it be true that women’s stunted education, lack of confidence, exclusion from the conversation and company of the great works of art and artists of their day made it unlikely that their self-portraits could have could have anything approaching originality?

Gentileschi, Knight and Carriera proved that women could produce great self-portraits. But these images were well known. Since the 1970s they had been displayed like banners by those advancing the cause of feminist art. In the back of my mind was a group of spectacular male self-portraits from the 16thto the 19thcenturies, in which the artists proudly held up nude drawings they had made. Where were the female self-portraits to match them? It was time for assessment. One way of dealing with the apparent discrepancy between male and female self-portraits were equally straightforward, simple images of the self at the easel with no attempt at a complex statement. But this defensive approach could never help reveal what made female self-portraits worthy objects of study. A breakthrough came when I decided to regard women artists as a subgroup. This seemed a bit more scientific somehow, related to methods of sociology or biology. As a subgroup women shared many characteristics of self-portraiture with the men – that went without saying. What needed to be discovered was where, as a subgroup, they differed from the main group.

So I bit the bullet and rather than bemoaning absences, considered what those absences meant. And here the context came into play. Research made it obvious that women’s lack of rigorous artistic training and society’s feelings about suitable feminine behaviour played a role in the way their self-portraits looked. Forbidden until the end of the 19thcentury to attend life drawing classes, it would have been neither credible nor acceptable to have shown themselves with life drawings in their self-portraits: such images would have been tantamount to advertising one’s lack of chastity.

Far from negative, this discovery made me aware that, unable to inhabit all the male self-portrait patterns, women adapted some or even invented some of their own. Categories emerged. Women artists with their children clustered at the end of the 18thcentury when Rousseau’s ideas of motherhood took root. Women artists at musical instruments emerged alongside the Renaissance idea of accomplishment and continued until the 19thcentury. Women artists with family members who assisted them. Rosalba Carriera was not the only one; in England c. 1820, Rolinda Sharples painted herself at her easel with the mother who encouraged her looking on. A takeover of admired images of the age was concentrated at the end of the 18thcentury when Maria Cosway in England and Elisabeth Vigee le Brun in France painted themselves in the guise of Rubens’ Chapeau de Paille, boldly publishing their rivalry with a revered artistic ancestor by usurping his sitter and placing themselves in her place. It became clear that women had never lacked ambition; they had merely disguised it under a layer of charm.

Evidence of the women’s cleverness renewed and deepened my passion. T he opening of art schools to women at the end of the 19thcentury made sense of the period’s burst of self-portraits by young women, their serious expressions and huge palettes evidence of their conviction that art’s glittering prizes were now within their grasp. Freedom to train was accompanied by the personal freedom afforded by study away from the family. In the first decade of the 20thcentury, the English Gwen Joh, penniless in Paris, took up modelling to earn some money. She did not like it when female artists tried to kiss her, but she returned Rodin’s passion while modelling for hisMonument to Whistler. Hardly surprising then to find she did several nude self-portrait drawings and watercolours during this period.

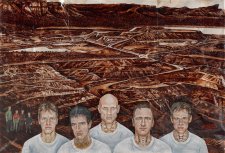

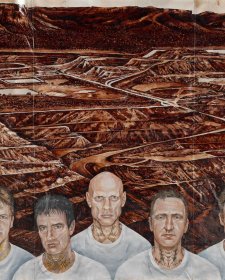

Since the 1970s, women all over the world have been taking self-portraiture into new directions. By using their faces and bodies as a base for more general issues, their works are a visible version of the slogan ‘the personal is the political’. In 1992, England’s Jenny Saville painted a series of huge nude women based on her face and body, but wildly exaggerated and larger than life. One of them is marked with contour lines. Spectators cannot fail to be reminded of maps showing hills and valleys, a brilliant – and ironic? – reference to the age-old link of landscape and female nudity. Where once women created self-portraits by manipulating the space in which the art world placed them, today they lead the way. My passion vindicated, I was ready to commit it to paper.