A pair of interesting additions to the National Portrait Gallery's developing collection of prints of popular identities and prominent figures of the colonial period has recently come to the Portrait Gallery from the collection of Leo Schofield AM.

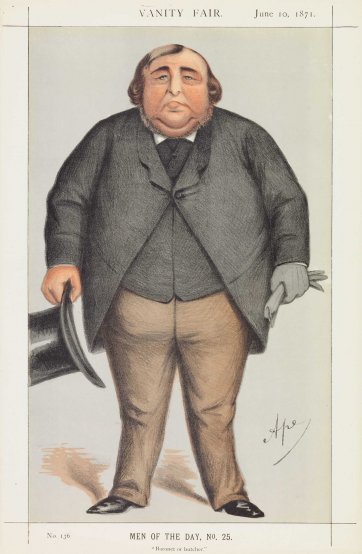

One, an extremely rare portrait lithograph from colonial Australia, is of naval captain and convict, John Knatchbull (1792?-1844). The other, a colour newspaper illustration print, is of Robert Lowe, Viscount Sherbrooke (1811-1892), politician. Although each of the two works is of interest in its own right, the two are very different. It is only the brief and unhappy relationship between the men they depict that connects them.

In 1842 Robert Lowe, Viscount Sherbrooke, having studied and tutored in law at Oxford, came to New South Wales. Lowe was an albino, and his doctors had warned him that he was likely to lose his sight before he turned 40. With this sentence hanging over him he crossed the oceans to try his luck as a lawyer, but with the colony in the grip of depression following drought, work was thin when first he arrived.

The eight years Lowe spent in Australia spanned an interesting period in the history of New South Wales. From 1840, when transportation of convicts was suspended, the colony was moving toward the official end of the convict system. Free migrants had been pouring in over the 1 830s, and some 80 000 were to arrive here over the following decade. Over the 1840s a delta of social cracks began to run between freed convicts, or 'emancipists'; free settlers who had come here by choice; 'free' settlers who were paupers who had essentially been shoved out of British workhouses; adults who had been born in the colony; and landholders. Squatters - a term originally applied to poor former convicts on the land, but soon designating a privileged new wealthy class - flouted the governor's limits on settlement, pushing out into land beyond the official boundaries that they occupied and stocked with no formal title. According to the Atlas newspaper, in 1844 out of about five million sheep in New South Wales there were some two million outside the defined area. An exasperated Governor Gipps commented that it would be as well to try to 'confine the Arabs of the desert within a circle, traced upon their sands, as to confine the graziers or woolgrowers of New South Wales within any bounds that can possibly be assigned to them'.

With the initial support of Gipps, from whom he soon became alienated, Robert Lowe became an unofficial nominee on the Legislative Council. In his first speeches in 1843, Lowe set out his vision of better government through laissez faire policy - reliance on the market, rather than State intervention, to regulate society. Although he was a fervent adherent to the principles of the British Constitution, he soon became a prominent opponent of the Crown initiatives that the Governor was obliged to implement. As systems of allocating land became increasingly regulated, Lowe Joined the Pastoral Association, formed to fight the new requirements for squatters to pay separate licence fees on contiguous stations and purchase lots of land from the government at decreed intervals and rates. The plan was to export revenue raised through these regulations to fund emigration from Great Britain. Lowe believed that it was not the business of the Crown to derive such a resource from the colony, the realities of life in which England's population, to a man, knew nothing about. 'This is the colony, that's under the Governor, that's under the Clerk, that's under the Lord, that's under the Commons, who are under the people, who know and care nothing about it', he wrote. The first issue of the weekly journal The Atlas, backed by the Association and launched by Lowe, contained a piece warning of the governor's 'new system of espionage', accusing him of 'attempting to model the whole corps of surveyors into a band of informers against the settlers'. There was a scathing poem about Gipps - as it turned out, the first of many:

He has crouched to the Crown as to something divine,

Till his fulsome compliance has sullied its shine.

Lowe wrote many articles for the Atlas lobbying for responsible local government, as well as contributing a good deal of Romantic verse, often on European themes ("The Moon", "Swiss Sketches"). Despite his commitments to the paper and to his legal practice he still found time to complete a report into popular education and drive home his recommendations for a state-supported, non-denominational school system. In 1848, nominated for one of Sydney's two seats in the Legislative Council, Lowe was returned a close second to William Wentworth. Henry Parkes called it the 'birthday of Australian democracy'.

Although in the case of the land question he had opposed government initiatives that would disadvantage squatters, Lowe spoke always on behalf of individual freedoms, not for a particular clique or class. On 11 June 1849 he chaired a huge rally on Sydney Harbour, assembled in the rain before the docking convict ship Hashemy, vehemently opposing the resumption of transportation. The thrust of the protest was that it was unjust of the Crown to sacrifice the social and political interests of the colony at large to the pecuniary profit of a fraction of its inhabitants - landholders, already benefiting from revised land orders of 1847, who could, on top of this, obtain free labour from a new wave of convicts. Again, Lowe's faith in freedom for all - and free trade for all - underpinned his objections. 'Behold a ship freighted', he cried, 'not with the comforts of life, not with luxuries of civilised nations, not with the commodities of commerce, in exchange for our produce; but with the moral degradation of a community - the picked and selected criminals of Great Britain.'

Lowe appeared regularly in Sydney courts in the years following his arrival. So it was that he came to defend John Knatchbull. Knatchbull, pictured here both dead and alive, served in the British navy before being convicted of stealing and transported to New South Wales. As a convicted criminal he was subject to a broad sample of convict experience. He became constable to the Bathurst-Mount York mail service and an overseer on the Parramatta Road before being convicted of forgery. Sentenced to death, he was sent to Norfolk Island instead. Here he was involved in a mutiny, but escaped justice by turning informer on his fellow mutineers. He obtained his ticket of leave in 1843,but the following year he was arrested for the murder of a woman named Ellen Jamieson. In a first for a British court, Robert Lowe raised the plea of moral insanity (insanity of the will, as opposed to the intellect) in the case. Despite the novel pitch and a subsequent appeal, Knatchbull was hanged on 13 February 1844.Lowe and his wife Georgians adopted Bobby and Polly Jamieson, the two children of Knatchbull's victim, and took them back to England when they returned in 1850.In defiance of his lifelong health problems Lowe lived a long time, and enjoyed a successful career as a columnist and politician, eventually holding the posts of Chancellor of the Exchequer and Home Secretary.

The artist of the Knatchbull portrait is unknown, but Carlo Pellegrini, who made the Lowe caricature, was a famous contributor to the London journal Vanity Fair. Chief artist between 1869 and 1888, Pellegrini, who worked under the name 'Ape' or 'Singe', mentored Leslie Ward, known as 'Spy', who succeeded him as the journal's principal illustrator and is today perhaps better known. Each Vanity Fair issue featured a cartoon, or caricature, satirically depicting a 'man of the day', as they came to be known. Reproduced by the relatively new colour printing process of chromolithography, these distinctive portraits were designed to be collectable, and many households and clubs amassed their own galleries of the most distinguished politicians, clergymen and lawyers of the time. Vanity Fair artists became well-known by their pseudonyms; these days, works by any and all of them tend to be described as 'Spy cartoons'.

This is the second generous gift of colonial works to the National Portrait Gallery from Leo Schofield. In 2002 he gave delightful portraits of architect Mortimer Lewis and his wife, pictured and described in Portrait 5 (Spring 2002).