John Schaeffer’s gift of George Lambert’s Self-portrait with gladioli 1922 crowns the Gallery’s collection of artists’ self-portraits. One of the most celebrated Australian paintings of its time, the portrait was a declaration of Lambert’s pre-eminence in Sydney’s art world of the 1920s.

In the history of Western painting, self-portraits have hadmany motivations -self' aggrandisement,self-evaluation, andsimple technical practice (using the most conveniently available portrait model). Australian painters are clearly conscious of these traditions. As a young artist, for example, George Lambertshared the enthusiasm of his generation for the tonal sobriety of Velasquez and equally for the flamboyance of the English exemplar of Bohemianism, AugustusJohn.

The first of these influences - Velasquez - was also strong in the portraiture of Hugh Ramsay, Lambert's Australian contemporary in Paris in the early years of the 20th Century. (In December this year, the Gallery will unveil another important addition to its collection of self-portraits, from the Bequest of J 0 Wicking, in which Hugh Ramsay depicts himself as a Velasquez figure in seventeenth-century dress). Lambert painted several self-portraits in the first decades of the 20th century. Initially he placed himself as one of a family group. But over time, glorious isolation became his preferred stance. In Chesham Street 1910 (National Gallery of Australia) he lifts shirt and loosens trousers to expose the massive expanse of his torso to his doctor. A later self-portrait of 1921 (National Gallery of Victoria) shows the artist in more ironic guise. Again, he is stripped to his underwear, yet he clutches pieces of military uniform in front of this chest, a comment on his ambivalent role of the official war artist - the non-combatant who uses his artistry to re-invigorate the quiet battlefield.

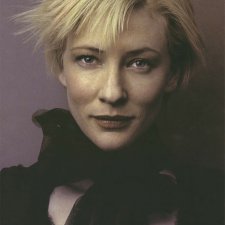

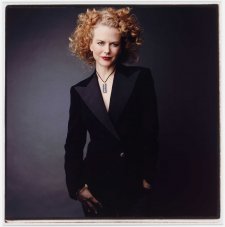

Self-portrait with gladiolishows no such selfdoubt. Here the artist, at 47, in the prime of his career, takes on the dandified appearance of the lion of society. Moreover, he takes the opportunity to demonstrate his prowess in flower painting. It was the high tide mark of Lambert's career. Between 1922 and his death in 1930 Lambert was consumed by work and illness. When he depicts himself in the later 1 920s it is as one prematurely aged; he draws himself at work, taking a break with the studio assistants for his last sculptural projects.

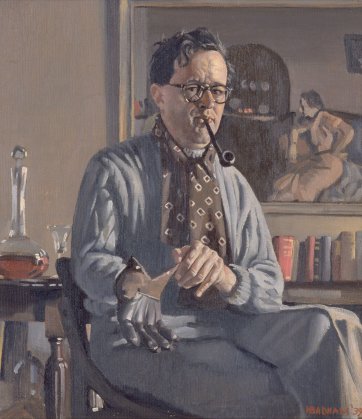

Herbert Badham's Self-portrait with glove 1939 owes much to Lambert's adoption of a persona in which to present himself. Although Badham's portrait is much smaller, the artist is similarly concerned to show his ability as a painter of still life objects; everything is rendered with an overall precision. But, the central figure, the artist himself, remains something of an enigma.

There are several parallels between Lambert's 1922 self-portrait and that of another towering figure of Australian painting, Fred Williams. Williams painted his self-portrait when he was in his early 30s, in 1960-61. Unlike Lambert, Fred Williams is not dandified, or supra-confident. Although he is well dressed in suit and tie, Williams eschews the cravat-and-beret image of the artist, preferring a more business-like style. He tells us that it is a serious thing to be a painter. Williams's palette is the finely modulated palette of earth tones he employed at this time to create a new landscape vision of Australia.

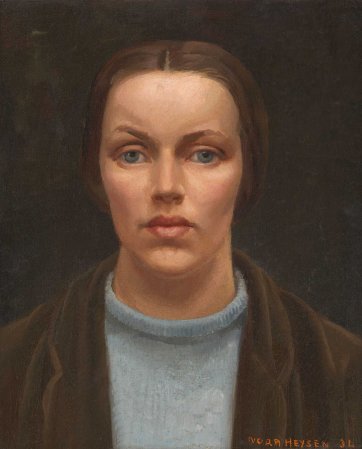

Central to the National Portrait Gallery's collection of self-portraits are three works by important women painters of the twentieth century - Nora Heysen, Stella Bowen and Grace Cossington Smith. Each of these selfportraits is intensely introspective. Although Nora Heysen presented herself in other selfportraits with the conventional trappings of the artist (smock and palette), the self-portrait of 1934 is pared down to the essentials. It was painted at a time when the artist was establishing her own distinct identity as an artist and in a new setting - in London. It is a small painting, but at the same time it is monumental.

Equally intense is Stella Bowen's self-portrait painted around the same time, in the mid 1930s. The work, too, belongs to a period of the artist's life in which she sought to re-establish an independent direction following the breakdown of her long-term relationship with the writer Ford Madox Ford. The portrait shares with Grace Cossington Smith's 1949 self-portrait the same accepting, undramatised central presence. In Grace Cossington Smith's self-portrait we have the sense, as in so many of her works, that the painting is not so much about a motif, but about paint, colour and light.

There are now a number of parallels and lineages we can see emerging in the Gallery's collection of self-portraits. The late Sir William Dargie is represented with an early declaration of his status as an aspiring painter; one of his best pupils, Janet Dawson, is represented with an authoritative tonal self-portrait work, painted when she was studying under Dargie. And on long-term loan to the Gallery, Arthur Boyd's early Rembrandt-like self-portrait stands at the beginning of his career as a painter who developed a colossal body of work from the fertlity of his own internal imaginative power.

2004 will be the focus of an emphasis on these important self-portraits in the Gallery's collection. In July next year the Gallery will be joining with the University of Queensland Art Museum to mount the first historical survey of the self-portrait to be mounted in Australia. The Gallery's self-portrait collection (that also includes fine examples by George French Angas, Jeffrey Smart and Roland Wakelin) will be shown in the company of some other iconic self-portraits in Australian art. It is anticipated that in future the two institutions will collaborate on an exhibition investigating the deeply interesting subject of self-portrait photographs in Australia.