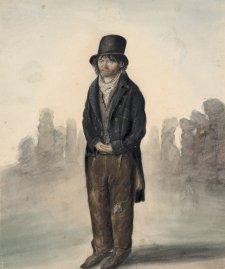

In Vagabondiana, his catalogue of the London underclasses, John Thomas Smith includes references to several negroes, noting: ‘black men are extremely cunning, and often witty; they have mostly short names, such as Jumbo, Toby, &c.’ He briefly mentions Black Toby, a beggar with no toes, and a six-foot man whose noble self-containment makes him think of Cicero, but his most substantial reference is to Charles McGee. For more than two decades, his was one of the best-known black faces in London, with his missing left eye and his frizzy, grizzled hair (one of his nicknames was ‘Massa Piebald’), sideburns and tufted pigtail.

According to Smith, McGee was born in ‘Ribon’ (Rio Bueno), Jamaica, in 1744, but the only other information provided from his early life is the fact that his father lived to the great age of 108. There is no explanation of his escape from presumed bondage, of how he came to be in England or of how he lost the eye. Dempsey’s inscription calls him an ‘American black’, which could suggest he was one of those slaves who sided with the British during the revolutionary wars and were later expatriated to London, who ‘swapped American shackles for the cold poverty of freedom’.

Whatever the truths of McGee’s first half-century, and however hard they were, we can be reasonably certain that, by 1800, he had established himself as crossing-sweeper at the intersection of Fleet Street, Fleet Market, Ludgate Hill and New Bridge Street. It was in this role that he gained what Smith calls his ‘great notoriety’. Although one source describes him as a ‘street philosopher’, ‘gentle man’ and ‘philanthropist’, and Smith notes that he was a regular attender at the meeting house of the Welsh preacher Roland Hill, his fame came not so much from his character, conversation, or evangelical Christianity, but was rather simply the celebrity of visibility. Blackfriars was a particularly busy part of the city, and McGee’s ‘stand’ or ‘pitch’ was ‘above all others the most popular, many thousands of persons crossing it in the course of a day’. Moreover, in addition to his continuous appearance beneath the Ludgate Circus Obelisk for a quarter of a century, he featured as the subject of at least three prints: one in Vagabondiana, ‘drawn on the 9th October, 1815, in the parlour of a public-house, the … Twelve Bells’, a single issue portrait engraved by George Roberts after J. Tillotson and a third by George Cruikshank in William Hone’s A slap at slop.

He even found literary representation. On McGee’s death in early 1825, a London poet (probably Thomas Hood) was moved to write ‘Twenty-one elegiac stanzas, to the black man who swept the crossing at the Obelisk, Blackfriars, and who lately died of age’. In addition to simple description, various melancholy puns — on dust and crossing and darkness — and meditations on charity, the poem contains three challenging verses on the question of freedom and class:

Thou wer’t a slave — yea, a black slave,

Even on English land!

Slave at a stand-still to a walk,

With stretch’d imploring hand!

A slave! — Why did not Wilberforce

Think of the blacks at home?

Where was thy Bennett, Clarkson, where

Where was thy best friend, Broom?

And neighbour Waithman too, could he

Rave of a free-born nation,

And all forget thy crusty fate

And small emancipation?

It is worth remembering, too, that while the slave trade had been outlawed in 1808, just a few years after McGee took up his ‘pitch’ at Blackfriars, slave ownership was legal under British law throughout his lifetime, and would remain so until 1834, 10 years after his death.

Collection: Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, presented by C. Docker, 1956

Dempsey’s People curator David Hansen chronicles a research tale replete with serendipity, adventure and Tasmanian tigers.

30 June 2017

Those of you who are active in social media circles may be aware that through the past week I have unleashed a blitz on Facebook and Instagram in connection with our new winter exhibition Dempsey’s People: A Folio of British Street Portraits, 1824−1844.

Dempsey’s people: a folio of British street portraits 1824–1844 is the first exhibition to showcase the compelling watercolour images of English street people made by the itinerant English painter John Dempsey throughout the first half of the nineteenth century.