Imagine a portrait. The image that comes immediately into your mind is probably a painting; lifesize or a little smaller, a face and shoulders, three-quarter length, in a frame. It is hardly surprising that this is the image conjured up by the word - the Western tradition is replete with portraits of this very type, among them some of the greatest works in the history of art, Titian's Man with a glove c. 1520 (Louvre), to choose an example at random. In Australia, at least since the advent of the Archibald Prize, portraiture has been in a broad sense, synonymous with portrait painting.

Yet what does 'portraiture mean at the end of the 20th century? At the outset of building a national portrait collection it seems an appropriate question to investigate. When Britain's National Portrait Gallery was established in 1856 there would have been a common understanding of the word 'portraiture' and consensus about the role of such an institution and what sort of work constituted a portrait. But the mid-19th century consensus about the nature of portraiture was to be increasingly challenged with the advent of photography which had occurred in 1839. Photography changed art completely, and portraiture was the medium of its development. Today photographic portraiture is ubiquitous; it seems strangely anachronistic to still think of portraits primarily as paintings.

The Possibilities of Portraiture examines some of the themes and motifs in portrait art which have engaged 20th-century artists both in Australia and elsewhere. It is arranged as a sequence of answers to questions about portraiture and its meaning which seem to have a particular urgency for artists working in the century after the arrival of photography.

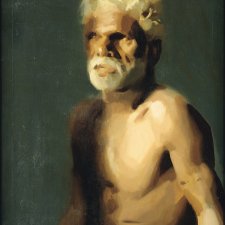

The first part asks a simple but fascinating question: How much is a portrait the subject, and how much the artist? By examining thirteen portraits of one subject - in this case Dame Mary Gilmore - by a number of artists, a singular feature of portraiture becomes clear; the portrait is at least half an art object and half a representation of a subject. For a collection of portraits, the corollary of this is inescapable; the success and interest of a portrait cannot be separated from its success in artistic terms, regardless of how otherwise interesting the subject may be.

The next part of the exhibition looks at some results of artists embracing this unique duality in portraiture. It looks at artists peering into mirrors, playing with reflected reality and the picture plane, using the reflected image as a metaphor for the way in which the artist constructs an illusory world. It is not surprising that this section is predominantly composed of self-portraits; in the 20th century the self-portrait has supported an endless range of psychological and formal possibilities.

Portraits look at the head, but looking at the head can be from many angles, and each angle has its own range of expressive capabilities. The face can confront - the subject looking directly at us seems to look into our world. What do these eyes seem to see? (The least confronting face is one with the eyes closed - withdrawn, meditative.) The face can be looked at from the side, from above, from behind.

Faces can appear multiplied hundreds of times, a single multifaceted face in James Gleeson's Portrait of the artist as an evolving landscape 1993, or hundreds of different faces in Zhuang Hui's remarkable panoramic group portraits of all the peasants of a Chinese village, or the body of students and teachers at one Chinese school.

Can a mask be a portrait? This is the question posed by Sidney Nolan in one of his most remarkable Kelly paintings. A black box - an icon which Nolan made synonymous with the outlaw Ned Kelly - lies disembodied in a landscape, and the title of the work, taken from contemporary court transcripts of Kelly's statements, gives the clue to the mask as a symbol: 'No-one knows anything about my case but myself.

Is it possible to have a portrait without a face? The answer is yes, a portrait can be emblematic - the sum of the things that a person has accumulated. Or it can have an absent person as its subject. In David Sequeira's Self-portrait in black and white 1998, five tiny self-portrait silhouettes rest on a series of books in which the world is divided into spheres of endeavour - the self is circumscribed and defined by language.

A common theme in all portraiture is the passing of time. Lives are circumscribed and portraits have chronicled and arrested this inevitable human flux. Portraits can have within them a temporal element, but this seems only to heighten the poignancy of the irreversibility of time. In the exhibition this idea reaches a crescendo in a selection from Andy Warhol's Screen Tests, a project which resulted in several hundred films made between 1964 and 1966. The originality of Warhol's Screen Tests lay in the artist's recognition of the possibilities of film to create portraits in time, and to create a framework which, as the title suggests, literally tests the personality of the subjects. Yet, projected onto a gallery wall, the Screen Tests have strong links with traditional portraits.

Most contemporary artists experimenting with portraiture are engaging with its inherent possibilities. Mike Parr's installation draws together many threads - portraiture as confession, portraiture as a kind of suspended animation, portraiture as a play on realism and, ultimately, reality itself, as the artist replicates his wax effigy with his own body.

A group of works which represent some responses to these possibilities is presented in the last part of the exhibition. Portraiture has inevitably been bound up with artists' investigations into the nature of painting, photography, sculpture, new mediums (such as holography and has been a central medium for probing into subjectivity, memory, identity and modernity.