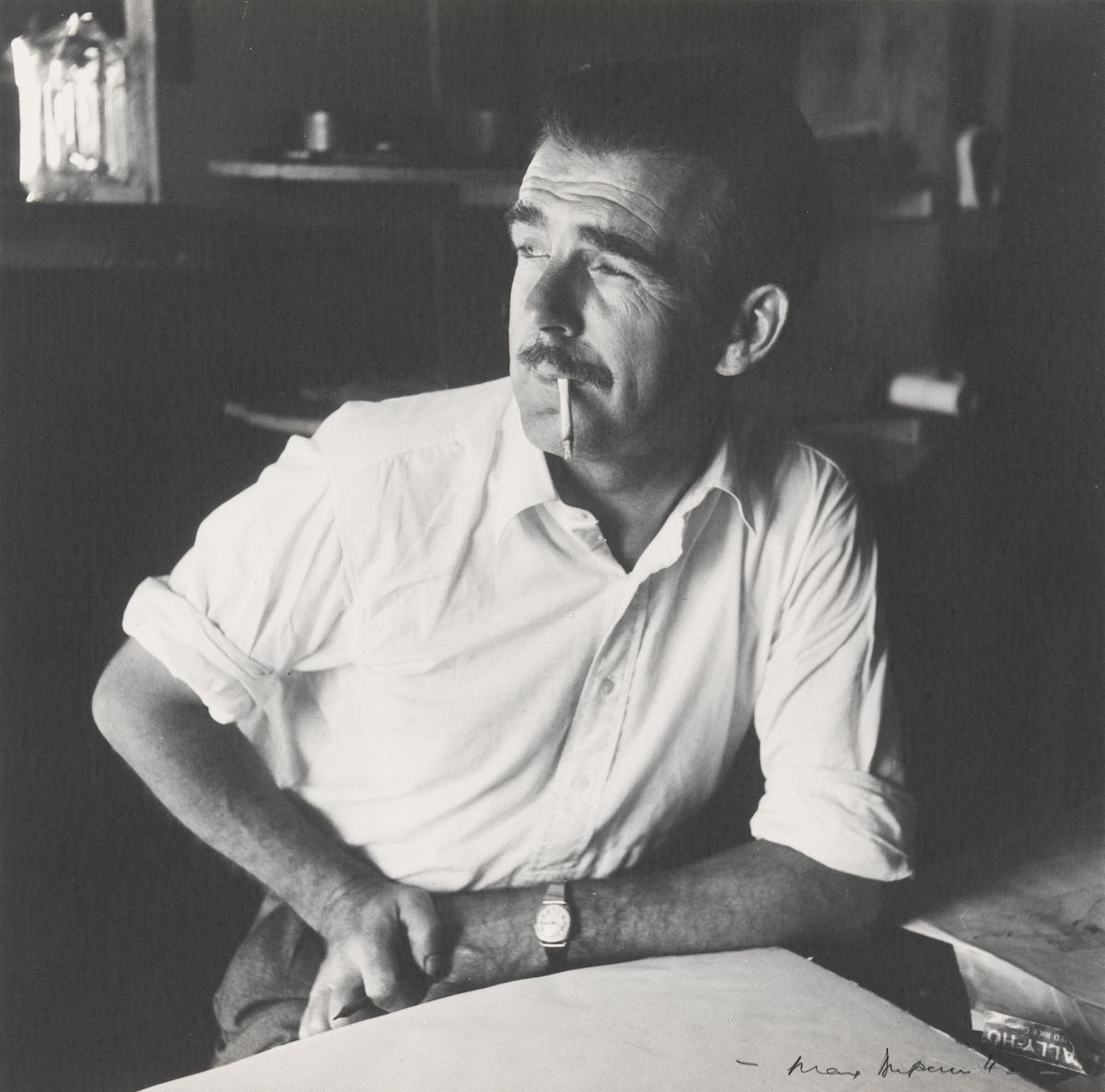

Dobell is of course, celebrated for his achievements in portraiture, winning the Archibald prize (1943, 1948 and 1959), the Wynne Prize (1948), and representing Australia at the 1954 Venice Biennale.

Curator Mary Eagle concludes her essay in the catalogue of the exhibition thus,

"Overall I see a dissonance in Dobell’s art and life. Such a wonderful beginning. Such a mixture of vulnerability and determination later. His paintings oscillate between an often crude idea and a technique of transparent sureness: a master of touch ‘his paint could be light, thin, delicate, precise, caressing, sliding, sharp, staccato, brisk, broad, rough or energetic. He could make it do anything he wanted’. Crude ideas carelessly painted: refinement with insight. Whereas Dobell’s engaged eye – at times his actual presence – presses into the majority of drawings in the endless early sketchbooks, declaring the complicit engagement of the artist with his subject, the quality of earthy closeness did not last. At furthest remove, the 1950s New Guinea paintings have a remote and dream-like quality. His most famous Australian works are portraits, with which he was involved increasingly after his return in 1939. Yet he was hampered imaginatively in the presence of his sitters. Typically his portrait drawings of the 1930s are of men or women asleep or engaged in some activity that absorbed their attention and in Australia his best portraits were completed long after the difficult face-to-face encounter. From 1944 until the end of his life the artist and his art suffered from too much attention. He felt trapped. ‘[I] couldn’t go anywhere without being pointed out. I remember all the tram stood up once to look at me sitting in a smoker. You know, through the glass. Somebody said, "Oh there’s Dobell in there" and the whole tram stood up. I hopped out at the next stop and went for my life trying to lose myself in the crowd.’ There was no escape. At Wangi ‘I couldn’t get away from people. I used to hide behind the hedge, and they used to come around saying, "This is where the mad artist lives", and I would get visitors all around, and holiday-makers watching.’ This was the same man who invited opinions about his art from anyone and everyone.

"The portrait of Dobell as liable to oscillate between extremes is appropriate to an introverted artist who identified himself within the humanist tradition of Rembrandt, Van Gogh and Daumier, looking not for the inner person but for what made that man or woman distinctive in the eyes of other people. It was the social imprint; the outline that the person made in the crowd; portraiture from the sociological angle. Dobell, when he was prodded by James Gleeson to explain what impelled him to paint one interpretation rather than another - was he attracted by the form or colour or line? – said ‘I don’t think of shapes…[but of] the feeling…It is more the literary value – what would you write about if you were describing it.’ The mannerism of Dobell’s art and the ornamental line which became his identifying style, typified other Australian artists of his generation. Hal Porter, Patrick White, Donald Friend and Ian Fairweather (to an extent) all developed in a remarkably similar manner. Porter’s style was ornamental, White’s inclined towards a mannered grotesque, Friend mad an art opf farce, and Dobell leaned to caricature. These writers and painters exaggerated. They had a theatrical bent and loved to ham it up. They marshalled the absurd, inflating, deflating. They focussed upon selective symbols of Australiana, swooping upon them, elevating the typical and honing its significance. They were hysterics, neither intellectual nor strategic but living through sensation and disaffection. They were open to the criticism of caricaturing their subjects. They had the same deep curiosity about human beings and the same habit of turning people into Gothic ornament. Their vision and their art, the imagery developed from sketch to study to more or less finished portraits never, I think, uncovered an inner ‘truth’ of personality, neither were new possibilities revealed at every step, rather they investigated the outward appearance, found what was memorable, and made it unforgettable. The phenomenon of these writers and painters, the generation of the 1930s, has yet to be explained. The issue of their Australian nationality is entangled with why they were so mannered."

Mary Eagle

Centre for Cross-Cultural Research, ANU, 1999