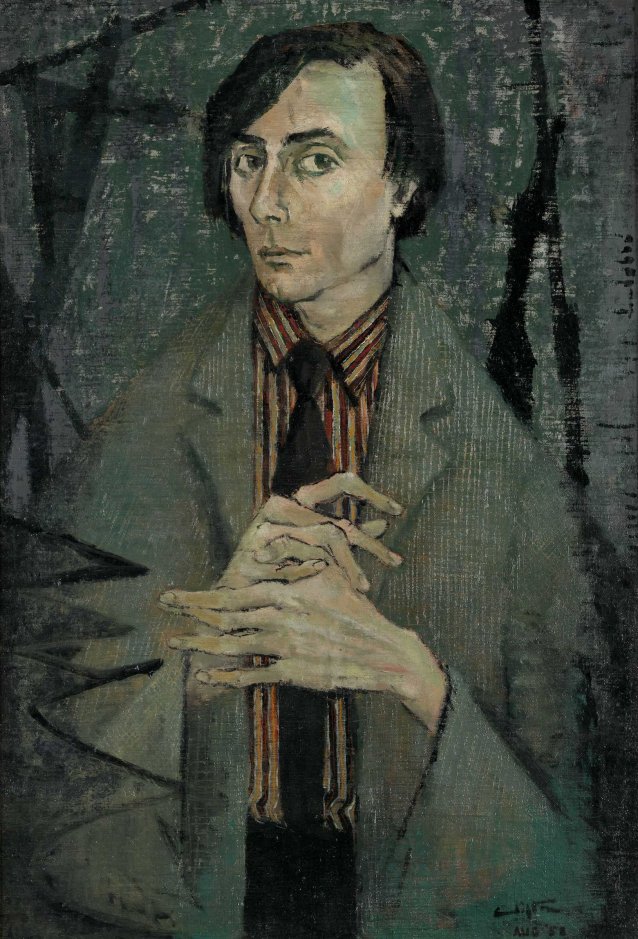

The first portrait ever acquired by the National Portrait Gallery depicts a callow, skinny Barry Humphries, his long fingers interlaced, his dark eyes burning. He looks jittery, as if he’s impatient to get going. Indeed, when Humphries was painted by Clifton Pugh in 1958, his brilliant career of exposing Australians’ prejudices and peculiarities was just getting under way. So, forty years later, was the National Portrait Gallery’s project to increase the understanding of the identity, history, creativity and culture of Australian people.

The portrait of Barry Humphries was given by the Melbourne philanthropists Gordon Darling and Marilyn Darling in May 1998. The official opening of the National Portrait Gallery in March 1999, on Gordon Darling’s 78th birthday, came six months before the tenth anniversary of the couple’s marriage. It had been a decade in which they had shared a passion for, and publicly advocated, a place that would testify to the ingenuity, inquisitiveness, intelligence and perseverance of individuals who had made a lasting difference to Australia. While there had been intermittent attempts to establish representative collections of portraits in the nineteenth century—the painter Tom Roberts was an early proponent of the idea—it wasn’t until nearly the end of the twentieth century that the Darlings’ combination of idealism, practical support and persuasive lobbying for an Australian National Portrait Gallery brought such an institution into being.

The Darlings are integral to the Gallery’s prehistory, its history, its present and its future. They sensed its absence; agitated for its establishment; showed what its collection might look like and embody. They donated and funded, and continue to donate and fund, artworks and commissions; they encouraged and encourage others to donate artworks and funds; they provided and provide means for staff development and research projects. Marilyn Darling was the chair of the Gallery’s board for eight years, guiding and overseeing its deliberations. Together the Darlings have seen the Gallery progress from a pipedream to a statutory authority; at the end of 2014, in his office looking down on St Kilda Road, nonagenarian Gordon Darling was delighted to scrutinise every word of the Gallery’s first annual report on his CCTV reader.

The couple

Leonard Gordon Darling, known as Gordon, was born in London to an Australian father and English mother in 1921, and schooled in England before serving as a major in the AIF during World War II. Gordon Darling was born into prosperity, but his forebears were self-made men. His great-grandfather, John Darling, who had left school in Scotland at 11, arrived in Adelaide in 1855, and worked in various jobs before joining a grain concern, of which he became manager. Employed by another, he took it over; and so began his career as the Australian colonies’ leading wheat trader. An impressive example of the Darlings’ mills, now heritage-listed, still stands next to Albion Station in western Melbourne. John Darling went into partnership with his son, also John, in 1872. They expanded their wheat exports, flour mills and shipping interests through the 1890s, John junior succeeding to the title of ‘Wheat King’ while his father served as a member for West Adelaide, Yatala and North District and involved himself with the Independent and Baptist churches, the Caledonian society and many philanthropic enterprises. The younger John Darling also served in the South Australian parliament. An early investor in the Broken Hill Proprietary Company, he became one of its directors in 1892 and was its chair from 1907 to 1914. His estate—minus 33 per cent death duties—went to his wife and nine children.

The last family member to occupy BHP’s ‘Darling seat’ was Gordon Darling, who was on the board of the company for a record 32 years from 1954 and was at that time the largest shareholder amongst the directors. For fifteen years during this period he was also chairman of Rheem Australia and Koitaki Ltd—the latter, a rubber concern in Papua New Guinea, where he had served during World War II.

Gordon Darling was surprised to be invited to accept the position of chairman of the board of the Australian National Gallery (later the National Gallery of Australia), which he held from 1982 to 1986. During this period he became close friends with the institution’s inaugural director, James Mollison; he judges that he taught Mollison quite a bit about finance, and Mollison taught him a very great deal about art. At the end of his period as chairman he provided funds for the establishment of the Gordon Darling Australia Pacific Print Fund, which has acquired some 7,000 prints for the national collection to date. In 1991 Darling established the Gordon Darling Foundation, which provides funding for a wide range of visual arts projects to institutions Australia-wide. Darling Foundation support enables arts professionals to pursue exhibitions, publications, research, symposia, travel and professional development that would be beyond the budget of their institutions. The Gordon Darling Foundation instigated and manages, in partnership with Museums Australia, the Museum Leadership Program, equipping senior industry staff with the skills and strategies to lead Australia’s museums and galleries on a global stage. At the National Portrait Gallery, in addition to assisting with professional development, travel, publications and exhibitions, the Gordon Darling Foundation has subsidised the three Anniversary Lectures, bringing noted international speakers to the Gallery’s audiences.

In October 1989, Gordon Darling married Marilyn Davis, née Skinner. Born in Brisbane in 1943, she studied science at the University of Queensland before working in the Department of Microbiology at the University of Melbourne in the mid-1960s, and undertaking postgraduate study in the Medical School of Monash University from 1973 to 1978. She worked as a scientist, but over time, her interests expanded to a variety of social and cultural concerns, including the Victorian Children’s Aid Society and the Lost Dogs’ Home.

When they met—introduced by Sheila Scotter, fashion maven and charity fundraiser—the Darlings had three marriages and six adult children between them. As exhilarated as they felt in each other’s company, their permanent union demanded careful consideration. On the very day that they decided that a life apart was insupportable, and that they’d merge their households, Gordon told Marilyn that it was his ambition to create a National Portrait Gallery in Australia— and that they should make it their project. In 1988, Marilyn’s art knowledge was scant; she was involved with the Victorian State Opera, the Dame Joan Hammond Award, the Music Foundation Appeal at Trinity College and Spoleto Melbourne (precursor of the Melbourne Festival). Still, she agreed. She quit all her committees, and, as she puts it, the couple ‘became a team of two’. They married in October 1989; Marilyn was ‘given away’ by James Mollison. Since then, the Darlings have become one of only four sets of married couples in which both spouses are Companions of the Order of Australia (the others are Derek Denton and Dame Margaret Scott; Marie Bashir and Nick Shehadie; and Richard Bonynge and the late Dame Joan Sutherland).

Uncommon Australians:

Towards a National Portrait Gallery

In the years leading up to the bicentenary of the English colonisation of Australia, Gordon Darling felt increasingly convinced that the time had come for a dedicated place to commemorate Australia’s notable men and women. He’d conceived a vision for a national gallery of portraits that was inspired and informed by visits to the portrait galleries in Washington DC and London, where he’d become friendly with the institutions’ respective directors, Alan Fern and Sir Roy Strong. With Marilyn on his ‘team’, he revisited Washington and London, and he also began to talk the idea of an Australian National Portrait Gallery through with as many people as he could in the ideal place for such an institution— Canberra, which owes its very existence to power-squabbles between Sydney and Melbourne. As it happened, Federal Parliament’s move to its new home in 1987 had freed up an appropriate building in which to establish a gallery of substance: Old Parliament House. Alan Fern gave the Darlings some sound advice. Recalling the scepticism that had greeted the arrival of the National Portrait Gallery on the American scene in 1962, he urged them to demonstrate, as publicly and as broadly as possible, their idea for an Australian National Portrait Gallery. In 1990 Fern told them to ‘borrow the best portraits you can, travel them, and if you’re offered a broom-closet in Old Parliament House, take it and expand from there.’

The Darlings gave visible force to their argument for a National Portrait Gallery by convening an exhibition, unequivocally titled Uncommon Australians – Towards an Australian Portrait Gallery, which toured Australia in 1992–93.

In their foreword to the exhibition catalogue they explained that the works in Uncommon Australians—116 portrait paintings, sculptures and photographs, curated by Julian Faigan from a list of subjects suggested by a diverse committee, drawn from every state and territory—did ‘not pretend to be a definitive roll-call, or a comprehensive one’ but were intended to ‘whet the appetite and to suggest the scope and variety that an Australian Portrait Gallery would encompass’. Uncommon Australians toured four state capitals; in Canberra, it was shown at the National Gallery of Australia. Men of renown launched each leg of the tour: Sir Ninian Stephen, Gough Whitlam, Sir Jack Brabham, Sir James Hardie and Sir Roden Cutler.

By the exhibition’s close, it was evident that there was widespread public agreement with the Darlings’ opinion that Australia deserved a National Portrait Gallery. So it was that the government announced that funds would be provided to support the establishment of such an institution in three rooms in Old Parliament House.

Base camp

From 1994 the National Portrait Gallery was a program of the National Library of Australia, declared the suitable manager on the basis of its existing collection of Australiana and its sound curatorial resources. The Gallery’s first exhibition, About Face: Aspects of Australian Portraiture 1770–1993 was opened by Prime Minister Paul Keating shortly before Easter that year. In his opening speech, Keating said that although he had resisted the idea of a portrait gallery at first, he had been persuaded that it was ‘one more gallery worth having’. The effect of the exhibition, he said, was ‘democratic in a totally uncontrived way. Intrinsically and inescapably democratic, like the country itself … To see this exhibition … is to begin to understand what a national portrait gallery might do. It might excite a wider interest in our history and society. It might encourage us to learn the story of Australia, and to better understand the stories of our fellow Australians … It might lead us to the conclusion that life is what we make of it—nationally speaking, that was never so true as it is now.’

As the umbrella over the National Portrait Gallery for several years, the National Library placed greater emphasis on displaying its collection of portraits. At the time of its creation, however, it was not intended that the National Portrait Gallery would acquire works. Rather, it would present three to four exhibitions each year that would draw on the ‘distributed national collection’ and private lenders. As a program of the Library the Gallery mounted ten exhibitions, but the Darlings found themselves disenchanted by the ‘generic’ direction the program was taking. In March 1995 the Weekend Australian ran a piece entitled ‘Portrait of a split’, telling the story of how ‘Private benefactors, Gordon and Marilyn Darling, have broken all ties with the National Portrait Gallery.’ With the change of government in March 1996, opportunities for the National Portrait Gallery to move forward as an independent collection revived. Again, America’s National Portrait Gallery was a catalyst. Early in his term as prime minister, the Darlings managed to facilitate a visit by John Howard to the National Portrait Gallery in Washington. Touring the Gallery with Marilyn at his elbow, Howard was impressed by the sweep of history it was able to present. Fatefully, however, he was hailed by an Australian tourist who, relishing his visit, told the new PM we should ‘have one of these at home’. Not one to underestimate Marilyn Darling’s determination, it took a long time for Howard to be persuaded that she hadn’t staged the encounter.

A building and a board

In 1997 the government put the National Portrait Gallery on a new footing, announcing that it would be severed from the National Library and the space available for its displays in Old Parliament House would be enhanced. Funding was provided for the transformation of the former parliamentary library and two adjacent rooms as exhibition spaces, with an area on the lower floor modified for art storage. Importantly, the gallery’s policies and activities would be guided by an advisory board appointed by the Minister for the Arts. An article in the Australian Financial Review noted the institution ‘boasts the sort of board that can conjure miracles,’ including chair Robert Edwards and deputy chair Marilyn Darling. Gordon Darling accepted the inaugural board’s invitation to become the founding patron of the Gallery; Janette Howard, wife of the serving prime minister, agreed to be the first chief patron (since then, Thérèse Rein, Tim Mathieson and Margie Abbott have agreed to take on the role). A cerebral and visionary young Director, Andrew Sayers, was appointed from the National Gallery of Australia, where he had been Assistant Director of Collections. At its first meeting in May 1998 the Board resolved that the Gallery would not rely forever on loans. It would acquire portraits, building a collection through a Government allocation that was subject, by its nature, to fluctuation; and through gifts.

Collecting

When the Gallery was established, Marilyn Darling felt confident to state that it was supported across the political spectrum. If it has remained ‘democratic in an uncontrived way’, in Keating’s phrase—and it has—it’s because of the variety of donors to the collection, as much as curatorial selection. But gifts from the Darlings themselves are notably varied. The first commissioned portrait, Howard Arkley’s Nick Cave 1999, remains one of the Gallery’s signature images. Yet an airbrush painting of the little-known, erstwhile drug-using genius of artlovers’ cult band The Bad Seeds is hardly something that those who know a bit about Gordon Darling might have expected him to fund. The portrait of Cave was not only a sign of the Patron’s trust in the judgement of the inaugural director, Andrew Sayers (which was well-founded), but a demonstration that Darling had never proposed to set up a shrine to business leaders, industrialists and investors of his own ilk, shaping a gallery that would reflect his own milieu and opinions.

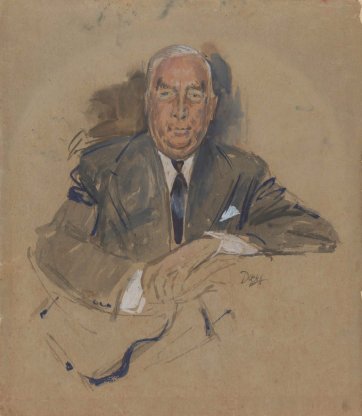

Certainly, it’s any donor’s prerogative to give portraits of figures he or she admires; in 1999 Gordon Darling gave a portrait of the towering Liberal leader Sir Robert Menzies and in 2000 he funded the commissioned portrait of John and Janette Howard by Jo Palaitis. In 2002 he funded the purchase of portraits of the tireless industrialist WS Robinson, a friend of his uncle Harold’s; and his own close friend Sir William Dargie, the latter in recognition of his key role in the establishment of the Australian National Gallery.

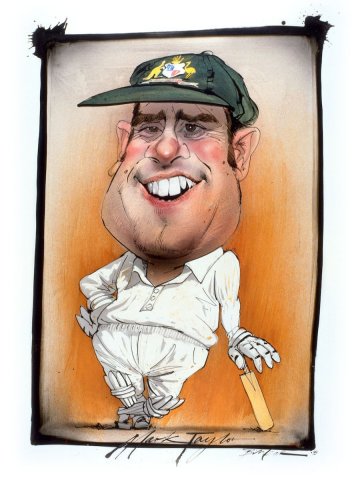

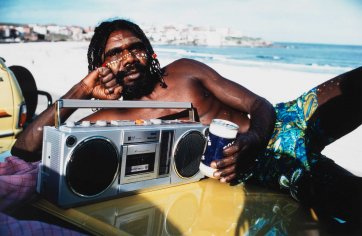

Then again, not long after the establishment of the National Portrait Gallery, Darling funded the commissioned portraits of Johnny O’Keefe by Ivan Durrant and Cathy Freeman by Kerry Lester, as well as the purchase of portraits of Mark Taylor by Bill Leak and Eddie Mabo by Gordon Bennett. Amongst the diverse works the acquisition of which he has funded in the years since are the commissioned photographs of Andy Thomas by Montalbetti + Campbell and Mick Dodson by Ricky Maynard; the bronze of Sir Jack Brabham by Julie Edgar; and the paintings of Nancy Wake by Melissa Beowulf and General Peter Cosgrove by Rick Amor. Works he has given from his own collection include portraits of Thomas Keneally and Sir Don Bradman, the latter on long-term loan until it was donated to coincide with the hundredth anniversary of the cricketer’s birth in 2008.

Cricket is a particular interest of Gordon Darling’s; his great-uncle, Joe Darling, was a Test cricket captain of Australia, playing 34 matches between 1894 and 1905, and features in a suite of photographs of cricketers who toured the United States in 1896, that was acquired in 2014 with Darling’s funds. The great Victor Trumper is represented in the collection thanks to Gordon Darling; so is Walter Lindrum, the scintillating billiardist whose achievements illuminated Australians’ gloom in the Depression. Former board member and portrait subject Leo Schofield has characterised the National Portrait Gallery as a ‘phenomenally successful metaphor’ for Gordon Darling’s ‘broad view of Australian life’.

An exemplary donor

Portraits of individuals as dissimilar as Nick Cave and Sir Robert Menzies were funded by Darling in a premeditated act of adventurous leadership, with a view to encouraging the government to match the example of private donors with public funds to build the collection. The more numerous, and more disparate, those private donors were and are, the better. Logically, an institution that celebrates the contribution of varied individuals to the shaping of the nation should itself rely substantially on the contribution of varied individuals to the formation of the collection. Moreover, an institution that’s supported at Federal level is protected against changing governments and fluctuating budget priorities if it’s demonstrably supported by donors of all kinds, and political viewpoints; hybrid vigour enables it to thrive.

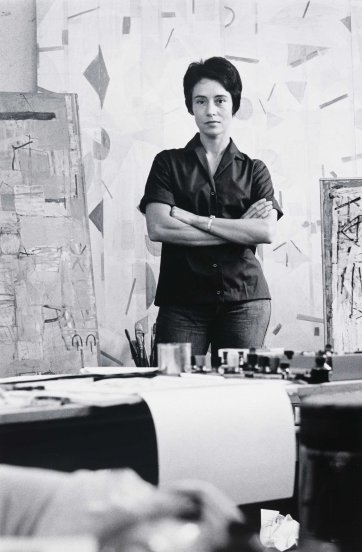

One of the first paintings acquired by the National Portrait Gallery was Fred Williams’s masterful Self-portrait of 1960-61, given by the artist’s widow, Lyn Williams. Even before Gordon Darling and Fred Williams served together on the inaugural council of the Australian National Gallery, Darling owned some of Williams’s paintings. But through the combined networks, knowledge and energy of the director, board members and staff, the list of donors to the collection rapidly lengthened and broadened: photographer Tracey Moffatt, theatre director Richard Wherrett, painter Davida Allen, lobbyist David Combe, judge Elizabeth Evatt, architect Penelope Seidler and the Margaret Olley Art Trust all gave works in 1998; of 92 works acquired in 1999, twenty were donated. On average, between 2000 and 2014, 32 people have given portraits each year. Many have given multiple works, so that a good majority of works in the collection in 2015 have been gifts. Most donors to the Gallery give portraits that they own. Some, including the Darlings, give cash that can be used to buy portraits. Over many years, funds donated by Gordon and Marilyn Darling have accumulated in a major account from which the Gallery can propose to draw, when offered the opportunity to purchase a portrait that would, in the opinion of the Director, fit the Darlings’ interests. There’s great excitement amongst Gallery staff and in the Darling household when such a work emerges.

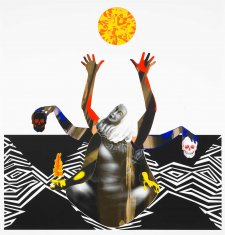

Sometimes portraits are pursued; sometimes they materialise; and sometimes—unusually amongst Australian art institutions—they are created expressly for the National Portrait Gallery’s collection. Andrew Sayers initiated the tradition of leading board members and curators in pursuing considered combinations of sitter and artist, seeking out practitioners not usually working in portraiture as well as professional portraitists for commissioned works. Many of the Gallery’s commissions—comprising more than 40 works at the beginning of 2015—are amongst the Gallery’s most exciting and popular portraits. Apart from keeping portraiture a dynamic Australian genre, the benefit of commissioning portraits is that the material and information that usually accompanies them into the collection—comprising preparatory sketches and paintings, photographs, interviews, notebooks, written accounts and so on— affords a fascinating insight into the process of representation and a strong ongoing resource for educators and researchers. Still, commissions tend to be costly. Marilyn Darling has funded some of the Gallery’s most adventurous, including the Victorian Tapestry Workshop’s woven representation of Dame Elisabeth Murdoch in 2000, Ah Xian’s delightful ceramic bust of John Yu in 2004, Brook Andrew’s huge screenprint collage of academic and activist Marcia Langton in 2009, and Sam Leach’s small, shiny jewel of a portrait of scientist Mandyam Srinivasan in 2015.

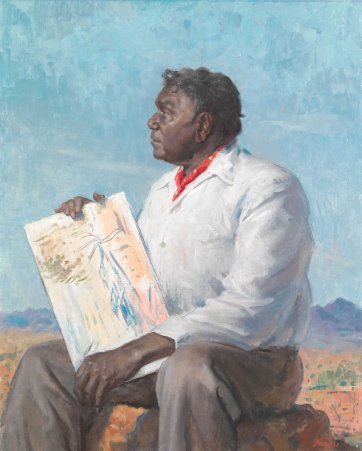

Marilyn Darling’s interest in medical science has informed some of her gifts; for example, she enabled the quietly audacious portrait of Peter Doherty, commissioned from Rick Amor in 2002, and the purchase of the photograph of another Nobel prizewinner, microbiologist Elizabeth Blackburn, in 2011. Indigenous affairs is also an area in which her donations have fallen: as well as the portrait of Langton, she funded the acquisition of the photograph of Ron Castan and William Dargie’s painting of Albert Namatjira. Each work extends the story that the Gallery is able to tell, and complicates its visual and narrative texture.

The swell of support

In July 2000 the Gallery was confronted with the opportunity to acquire a work that was in every sense a ‘foundation portrait’ for the relatively young collection: the Portrait of Captain James Cook RN 1782 by John Webber, which had, at one time, been in the possession of Alan Bond. Andrew Sayers endured six months of nervewracking international negotiations to bring matters to the point at which the Commonwealth purchased the work with the assistance of benefactors Robert Oatley and John Schaeffer. Oatley, a close friend of the Darlings’, has remained a generous supporter of the Gallery’s operations, and in 2002 John Schaeffer gave George Lambert’s Self Portrait with Gladioli 1922, a work from his own collection that sprang immediately into the front ranks of the signature images of the National Portrait Gallery. The Ian Potter Foundation, named for the financier who was a good friend of Gordon Darling’s for many years, has enabled the purchase of a number of destination works including Jean Rigaud’s portrait of Johann and George Forster.

Tim Fairfax initiated his exceptionally magnanimous support of the Gallery in 2001 with a joint gift with Gordon Darling—a large collection of photographs by David Moore. In time, there appeared very significant benefactors who were entirely unconnected with the Darlings, notably the Canberra developers and investors, mother and son Sotiria and John Liangis. That said, some of the Gallery’s most beguiling portraits have come from donors without substantial means; and that, too, accords with the Darlings’ vision of an organisation in which all kinds of Australians have a stake.

A permanent home

The Darlings have not only been important to the Gallery as initiators of the institution and contributors to its collection. While the idea for the gallery might have come to Gordon Darling, and he remains a steady, patrician front-man for the institution, it was Marilyn Darling’s unflagging efforts that carried the organisation through to a permanent home.

By the time Marilyn Darling assumed the chair of the National Portrait Gallery board at the end of 2000, the Gallery was expanding irrepressibly; but despite the success of its programs from 1999 onward its accommodation continually constrained the ambitions of its young director. In 2001, after briefly investigating the feasibility of expansion in Old Parliament House, the board agreed that it was important to maintain traction on both sides of politics with a view to obtaining more display space for the Gallery. In 2002 the Gallery seized the opportunity to lease a vacant contemporary structure at Commonwealth Place by Lake Burley Griffin in the Parliamentary zone. With the addition of wall space at Commonwealth Place, the Gallery’s temporary exhibition schedule expanded to eight or nine shows each year. While the different tone of the two display spaces encouraged a diverse exhibition schedule, neither labyrinthine Old Parliament House nor the sparkling, airy waterside gallery was designed as an exhibition venue. Neither the director, nor any member of his staff was in any doubt, on any day, as to the intensity of Marilyn Darling’s interest in the Gallery’s progress, and she continued to remind the government of the institution’s popularity and potential. In a recent interview, recalling her struggle, she said wryly that ‘a building in Canberra is not a vote winner’. She was asked why she didn’t seek private-sector funding. She replied that if the government provided the walls, she would ensure that portraits to put on them flowed from the private sector. John Howard said, chuckling, in an interview in 2013 ‘It’s fair to say that Marilyn was relentlessly active in her advocacy’ for a dedicated building. In November 2004—as the Labor opposition, under Mark Latham, posed a serious threat to the institution’s future—the Howard Government took the bold step of promising, if re-elected, to provide $50 million for a dedicated building for the National Portrait Gallery. In fact, the government ultimately committed $87.8 million to build the institution. The difference between the amount originally earmarked, and the final cost, came in instalments gruellingly negotiated by Andrew Sayers and Marilyn Darling in Parliament House.

There was intense competition to design the new National Portrait Gallery premises, on a site adjacent to the High Court of Australia. Marilyn Darling recalls that the quality of the submissions received reflected the robustness of the architectural brief, meticulously assembled by Sayers and his senior staff. The winning entry, selected from a shortlist of five and designed by the Sydney-based architectural firm Johnson Pilton Walker Pty Ltd, was announced in November 2005. The plaque marking the start of construction was unveiled by Prime Minister John Howard and Mrs Howard in August 2006. From that moment on, spearheading the board, Marilyn Darling wore a track between Old Parliament House and King George Terrace, donning the hard hat to scrutinise developments through bright blue eyes. Early in 2008, as the slim parallels of the building began to materialise, Richard Johnson was awarded Australia’s highest architectural honour, the Gold Medal of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects. Since then, the building has won more architectural awards than any other in the country. At the beginning of December 2008, Labor Prime Minister Kevin Rudd declared the building open. Five years later, Gordon Darling was asked about the most satisfying moment of his career. He said ‘I think the completion of the new building for the National Portrait Gallery—walking through it and seeing the hang being finalised. And then next day the official opening and the excitement of the hundreds who attended. It was an overwhelming happy moment for us both.’

Uncommon Australians

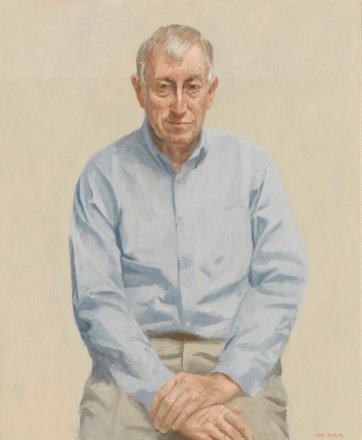

Visitors to the National Portrait Gallery typically pass James Angus’s bright orange Geo Face Distributor, commissioned for the eastern courtyard with funds provided by Gordon Darling. They enter the front doors into the Gordon Darling Hall to be greeted by Shen Jiawei’s portrait of the Founding Patron himself, conveying his qualities of courtesy, generosity, intelligence and resolve.

They pass the plinth with a sumptuous floral arrangement funded weekly, since the building’s opening, by Marilyn Darling. Passing through the Marilyn Darling Gallery, a jewelbox for focus exhibitions, they make for the contemporary works in Gallery 2, where they might see portraits of John Yu, Peter Doherty, Elisabeth Murdoch, Elizabeth Blackburn, Marcia Langton, Sass and Bide, Andrew Sayers or Mandyam Srinivasan—all made available to the Gallery through the largesse of Marilyn Darling, whose own glowing portrait by Ann Zahalka, funded by Tim Fairfax, hangs there.

They may proceed through internal spaces named in celebration of benefactors spurred to contribute many millions of dollars to the development of the institution and its collection: the Oatley, Schaeffer, Fairfax and Potter galleries; or they may return to the Liangis theatre. Throughout their time in the collection display, they can trace not only Australia’s post-settlement story, but the gallery’s own progression. Many of its highlights were loaned to Uncommon Australians, and have been given to the Gallery since: Walter Lindrum, Hudson Fysh, Essington Lewis, Roy Rene, Frank Packer, Harry Seidler, Thomas Keneally, Fred Williams, Warwick Fairfax, George Moore, Don Bradman, Albert Namatjira, Thomas Keneally, Ian Potter, Charles Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm are old friends in this context. Like them, the great majority of men and women represented in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery have worked extraordinarily hard, or shown an uncommon degree of humanitarianism, to reach a level of achievement that has benefited a great number of others. They’re all uncommon Australians—as are Gordon and Marilyn Darling, of whose union the National Portrait Gallery will always be the emblem. Sitting on the sofa in the Gordon Darling Hall, beside the portrait of the man himself, the visitor may well reflect Lector, si monumentum requiris, circumspice.

15 portraits

Related information

Uncommon Australians

Towards an Australian Portrait Gallery

Touring exhibition, 1992In 1988 philanthropists Gordon and Marilyn Darling decided to make an Australian portrait gallery a reality, overseeing the development of the 1992 touring exhibition Uncommon Australians.

Portrait Exploration: Art and Identity

Visual Arts (upper primary)

Join us for an engaging and interactive program tailored for upper primary students, where they’ll develop the confidence and critical thinking skills to interpret portraits.

Portrait Quest!

Civics and Citizenship (upper primary)

Join us for an interactive, curriculum-aligned program that explores the lives and contributions of significant Australians.