The consolidation of the Australian penal colonies coincided with the advent of purportedly scientific theories that sought to understand human behaviour through an analysis of the body – specifically the study of the skull and facial features.

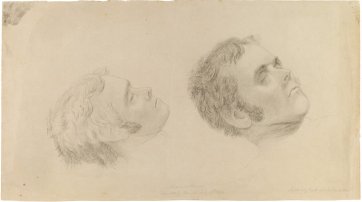

Though initially developed by physicians, phrenology was taken up by certain non-medical practitioners who applied the theory to social questions such as education and criminal reform. With their convict and ex-convict populations, the Australian settlements represented a rich vein of material and a regular, powerless source of subjects for officials engaged in the consideration of such ideas. Colonial-era surgeons – and, subsequently, university medical departments – utilised executed felons for dissection, and analysed post-mortem portraits for evidence of the physiological causes of criminality.

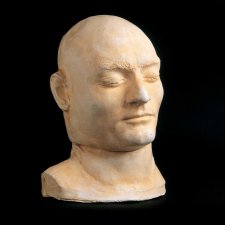

A concern that innate criminal tendencies could be passed on to subsequent generations resulted in the creation of death masks, which were collected and studied by anatomists and used as props in lectures delivered by practical and travelling phrenologists. For much of the 19th century, portraits of dead criminals were also put to commercial uses, such as in the production of lithographed souvenirs of malefactors, or in the ghoulish and sensationalised waxworks displays of bushrangers and assorted infamous offenders.