The concept of kinship is complex, and shapes social organisation and interactions. Kinship, including moiety, totems and skin names, determines how people relate to one another, as well as their roles, responsibilities and obligations to one another, the environment and ceremony.

“Well, my grandmother was Nambin, because my mum and dad were married the right way. And that’s my Ngawji, like my grandmother’s skin name. My father’s mother. The story for Nambin is the same one for Garnkiny (the moon), who is the skin Julama (crocodile).”

The story of Nambin and Garnkiny is told through many Warmun paintings, as the Garnkiny Ngarranggarni (Moon Dreaming). Garnkiny fell in love with his mother in law, the beautiful black headed python, and this was forbidden. The tribe disallowed the relationship and Garnkiny got angry. He cursed the tribe, saying they would die and they would never come back, while he, the moon, would come back every night forever.

“My granddaughter’s skin is Nyajarri. Nyajarri is a bush turkey and its blackfella name is Bingrrbal. We tell ‘em all the kids, this lot of animals, they got skin name and blackfella name. Well this one, he bin travelling with the emu, and this one, this bush turkey, he had been having too much bush tucker, and so he (she) said “No, I gotta camp here, it’s dark.”

Shirley talks about the Ngarrangarni (Dreaming) that relates to the bush turkey. The bush turkey was travelling with the emu, and they got loaded with food during a regular hunting trip, and the emu wanted to keep on going, but the bush turkey got tired and refused. The place that was loaded with this bush tucker is in present day Violet Valley.

“Well, she (Nangari/crow) is important for kids because you know the story of Santa Claus, well our old people they used to say that the crow, we call it Wangganal, that crow is like a Father Christmas; because it used to go out and scavenge for food, and that’s why they been having that idea, that she bin collecting all the presents for kids. There is also that song for it: ‘Wangganaly, Wannganal-y, Gooloo Gooloo Yarra Ma Nguyu… Bulbambi Binbijayu … Wangganal-y , berrawerra yinbijayu’. That means, they are getting happy that he bring ‘em presents and send them out for Christmas holiday at the school. Nangari is also a Gija skin, and we got ‘em dreamtime story for this one up near la Warmun hill. My skin and my sisters’ skin is Nangari, the crow.”

Shirley describes how there are a several reasons why the crow is significant to her and her culture. The first she associates with a special modern day ceremony for school children, that was invented by the elders of Warmun. The very last day of the school year in December is one of celebration, where Wanggana comes to visit all the children, and gives them presents (after giving them a fright). The event, which can be interpreted as

both cruel and kind, is one for all Warmun children. They get to go home with a gift after a special school assembly, where all families are invited.

Nangari is the skin name for Wangganal (the crow) and it is also Shirley’s skin. In Gija kinship systems, Nangari helps define who Shirley is within her wider family and community, and how others may relate to her.

Marlowal (the rock wallaby) is also used to refer to Nagarra skin. The Marlowal was pouring all these rocks to form the caves so that all the other wallabies could live in there with their families. These black rock formations can be seen in present day Warmun and around Norton Bore, Shirley’s paternal ancestral lands. They’re called ‘Thurru thurru wanannyanda’, meaning ‘pouring around’.

“That’s the Ngarranggarni for this one now – the Marlowal, that girl wallaby… You can see some of them black-black rocks around here.”

Some people eat the Marlowal, it’s tasty, and they used to hunt them all around Gija country. Marlowal or Nagarra is also my cousin-sister (my mother’s brother’s daughter); my Thamanyil.

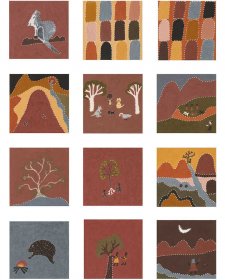

“This is my mother, Nyawurru (emu). This is me, Nangari (crow). This is my daughter, Nangala (brolga). This is my grand-daughter, Nyajari (turkey).”

Shirley has painted the four skin names from her mother’s side. These skin names are for Gija women, and they repeat after four generations. Each skin here refers to an animal, and helps Gija people understand their place in society, and their relationships between each other, particularly, for marriage, and marrying one’s ‘straight-skin.’

Looking at the correct straight skin relationships, Nyawurru (the emu) can marry Nambin, the black-headed snake’s son. Nangari (the crow) can marry Naminjili, the curlew bird’s son, or Nambin’s brother. Nangala (the brolga) can marry Nagarra, the snappy gum flower’s son. Nyajari (the turkey) can marry Nagarra’s brother.

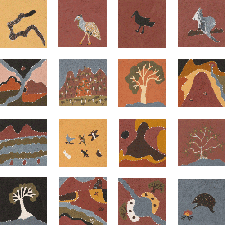

“This is my grandmother from my father, Nambin (black-head snake). This is my aunty (father’s sister) Nyawana (white-chested kangaroo). This is my father’s niece, Nagarra (yellow flowers of the snappy gum tree). This is my great-grandmother (father’s grandmother), Naminjili (curlew bird).”

Shirley has painted the four skin names of her paternal grandmother’s side. These skin totems are different to her mother’s side. For Gija people, there are a total of 16 different skins for men and women combined: eight skins for women that come from paternal and maternal sides, and eight skins for men. Each skin here refers to an animal or plant, and helps Gija people understand their place in society and their relationships between each other, particularly for marriage, and marrying one’s ‘straight-skin.’

Looking at the correct straight skin relationships, Nyawurru (the emu) can marry Nambin, the black-headed snake’s son. Nangari (the crow) can marry Naminjili, the curlew bird’s son, or Nambin’s brother. Nangala (the brolga) can marry Nagarra, the snappy gum flower’s son. Nyajari (the turkey) can marry Nagarra’s brother.

“This Nangala (turtle) is special because she was looking for water for her grandson, the crocodile. She had the crocodile wrapped in paperbark and carried him all the way to my country looking for water, with a stick in the other hand. They bin travel south and she busted the ground (with her stick) and they found water.”

Nangala is also Shirley’s daughter’s skin, and it can take on many forms such as the brolga, sandfrog or turtle. They are all the Nangalas, and they are all female.

“This emu is special for me because I was an emu when that old man (my uncle) killed me and they (my aunty and him) cooked it (the emu) and my mum and dad ate it, and that’s when my mum felt sick and was vomiting. That’s when she knew she was pregnant with me. Also, in Gija way, I can’t eat an emu, because that’s my mother’s skin. And my Jarrin (my reincarnation).”

“This the brolga, his skin name is Nangala.”

Nangala is also Shirley’s daughter’s skin, and it can take on many forms such as the sandfrog or turtle. They are all the Nangalas, and they are all female.

All images © Shirley Purdie/Copyright Agency, 2020