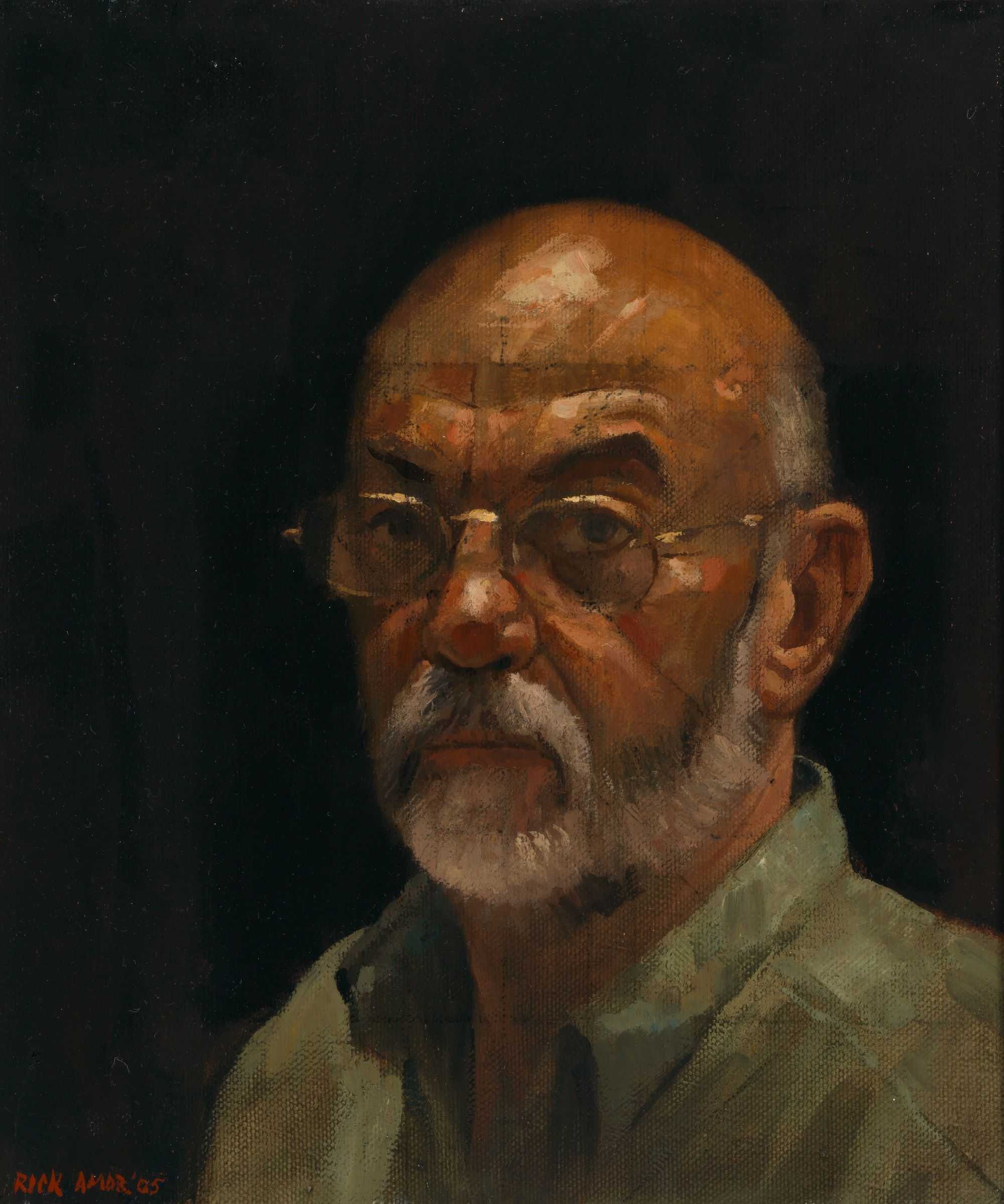

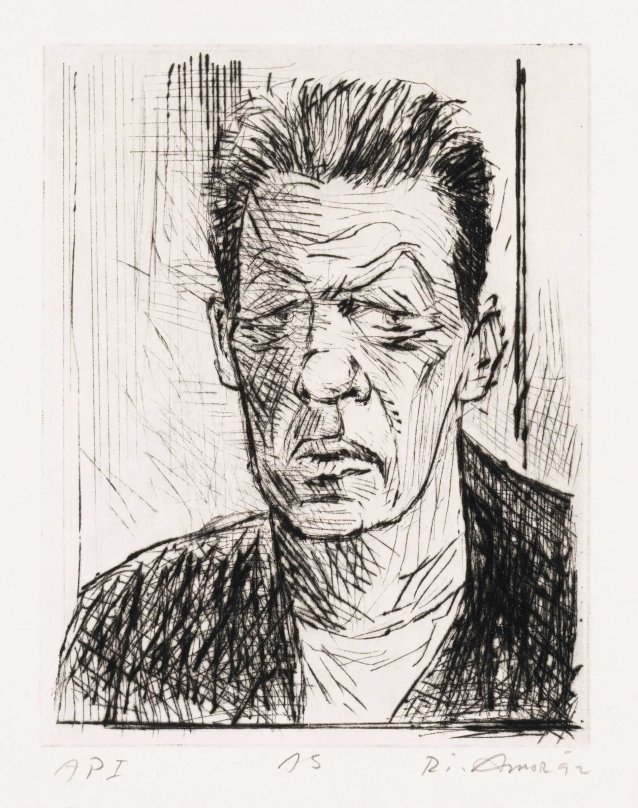

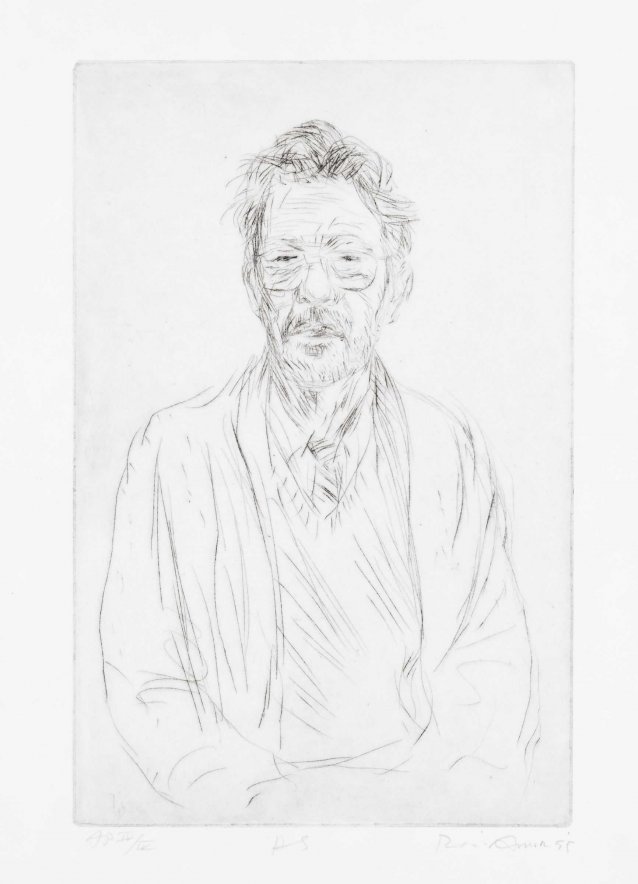

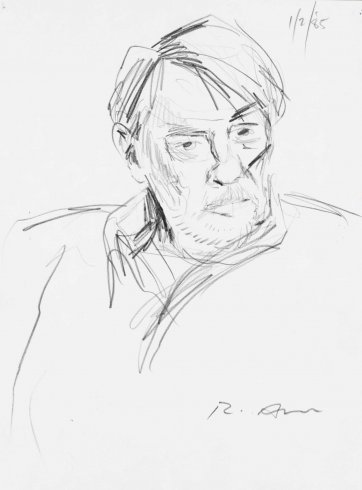

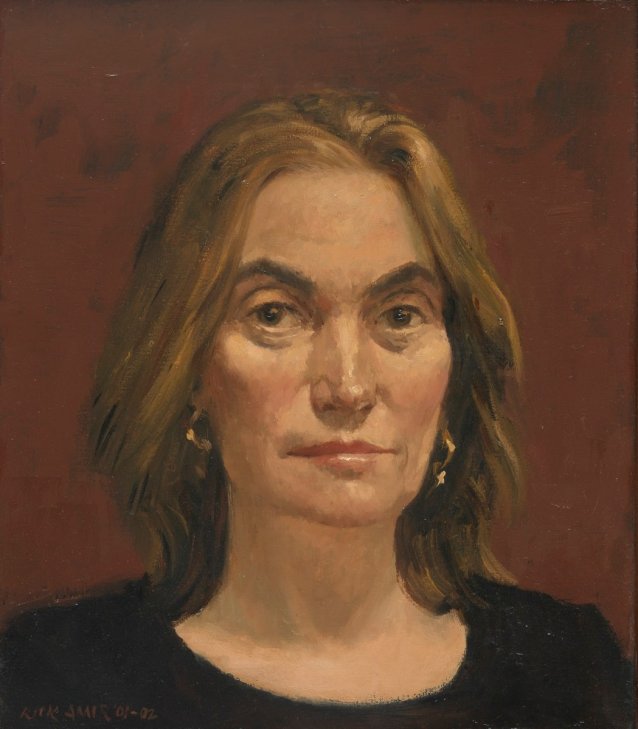

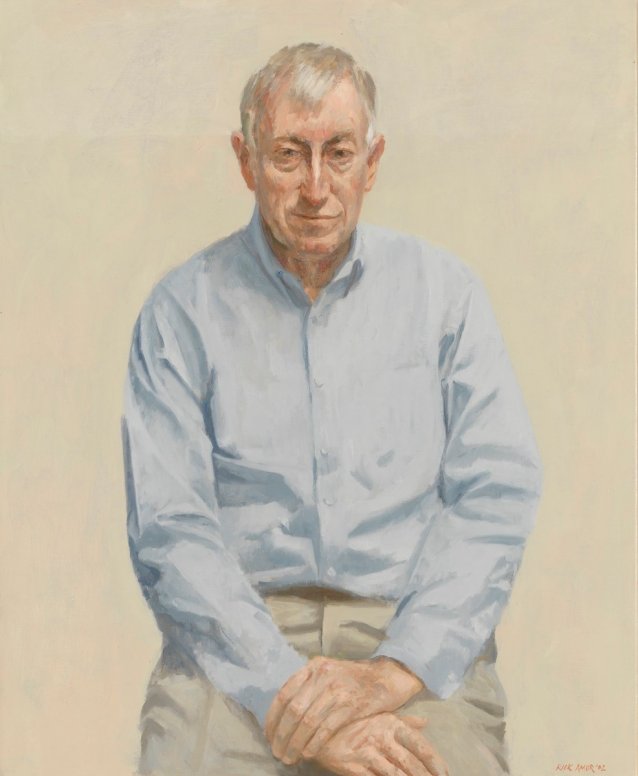

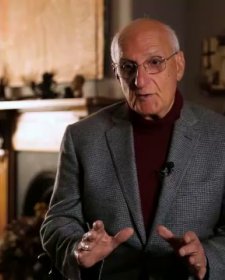

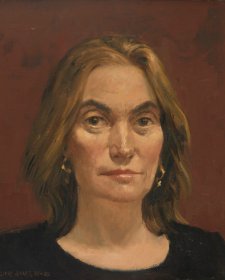

Sitting in his regular lunch spot in Fitzroy, Rick Amor smiles at something I read out from the Guardian – a quotation from a painter who says ‘I’m like a bank worker. I come to the studio five days a week and do my job. I pay attention to detail and try not to make mistakes.’ He nods, and adds ‘I just paint what I want. If people buy it, that’s fine. If not, well ... ’ and shrugs – as he’s now, after more than 30 years’ exhibitions and sales, in a position to do. Amor seems to know everyone without ever having been part of a scene. In the 1970s and 1980s, Robert Rooney managed to take portraits of 75 Melbourne arts identities without including him. He hasn’t been profiled in slick supplements of the weekend papers; indeed, as he was ‘emerging’, sexy and wild, there was no Good Weekend or Financial Review Magazine. In 1999 he made the front page of the Age, but at least until he was interviewed for Dumbo Feather in 2012, he wasn’t a household name. Perhaps journalists hesitated because his paintings are sullen; masculine in colour and mood; threatening. He has a dark countenance, a noble mien, and in the self-portraits he makes most years, he alternates between a frown and a scowl. Yet since the mid-1980s he’s made an increasingly comfortable living out of making the sombre and discomfiting art he feels happiest making. Without ever having won the Archibald, he’s gained a reputation as the most credible of Australian portraitists; the one with the best schooling and the most experience; the one who fusses least. In person, he’s affable. He’s endowed several art prizes. The subject of several monographs himself, he has hundreds of books on art that he knows inside out, and pulls down excitedly from his shelves. He reads a lot: all kinds of things.

Rick Amor, born in 1948, spent his early childhood in the Melbourne beachside area of Long Island, in Frankston. His father was a primary school teacher; the family was bohemian. When Rick was twelve, and the only child at home, his mother died. As he entered his teens he showed a strong talent for art, and he completed a Certificate of Art course before enrolling at the Melbourne’s National Gallery School, then in Swanston Street near the old Museum and State Library. Taught by John Brack from 1966 to 1968, he won the NGV Gallery Society Drawing Prize and the Travelling Scholarship, which, while providing insufficient funds for actual travel, allowed him to paint full-time for six months. In 1970 he married Tina Schifferle, with whom he played in a jug band; they had a son, Lliam, and Amor worked briefly as a surveyor’s assistant, painting by night in their rented flat above a shop in Balwyn.

Through John Brack, Amor met the influential Melbourne art dealer Joseph Brown, who took an interest in the young painter’s work. It was through his intervention that Amor and his family stayed briefly at Dunmoochin, at Cottles Bridge near the artists’ hub of Eltham. Dunmoochin was the hand-made home of the painter Clifton Pugh, who had been a judge of the National Gallery Society Drawing Prize awarded to Amor. He and Amor met in September 1972 at the opening of Joseph Brown’s Contemporary Australian Portraits, in which both artists were represented. Brown, keen for his promising new artist to live somewhere conducive to creation, facilitated their accommodation there over December 1972, and, soon after, at a cottage attached to Joan and Daryl Lindsay’s home Mulberry Hill, at Baxter on the Mornington Peninsula. Sir Daryl Lindsay had been director of the National Gallery of Victoria for fifteen years, and was a painter; his wife Joan, author of Picnic at Hanging Rock, was an artist too. Amor was to remain at Baxter until 1984, working on paintings in between carrying out odd jobs around the property.

The beginning of 1974 brought the Amors a daughter, Zoe, and Rick Amor’s first solo exhibition. Portraits in that show attracted conflicting criticism. Oddly enough – because from a historical viewpoint, some excellent portraits were being produced – it was a time when portraiture seemed a moribund genre. So it was that Patrick McCaughey admitted that all painters were at a loss when it came to the commissioned portrait; but he was still dismayed by Amor’s ‘slick and commercial’ style. Alan McCulloch, by contrast, judged him ‘the only star so far to emerge from the era of John Brack’s tutelage’. A year after the solo show Joseph Brown suggested that he seek another dealer, and finding himself without financial support, he began illustrating books and producing propaganda for the unionised Left.

Gough Whitlam’s dismissal in November 1975 – just after Amor had been awarded an Arts Council grant – ignited the artist’s political engagement. He joined the Frankston branch of the ALP, and from 1975 to 1983, working for the Labor Star and Tribune, he produced a spate of cartoons attacking the Fraser government. In 1976, with support from the secretary of the Builders’ Labourers’ Federation, Norm Gallagher, he made a series of drawings of labourers on a Melbourne shopping mall development. Over the next few years, supported by George Seelaf, the Victorian Trades Hall Council arts officer, he made portfolios of pictures depicting the construction of the West Gate Bridge and slaughtermen at work. The Miscellaneous Workers’ Union commissioned him to make a mural for its Capel Street headquarters; in 1978 he held a large exhibition at the Trades Hall Gallery; and in 1980 he became the first artist-in-residence at the Victorian Trades Hall Council. At the same time, he was illustrating books. A series for hesitant readers required him to work in a comic format. He drew break-out boxes in science textbooks. He drew scenes for Joan Lindsay’s Syd Sixpence and made linocuts of bush characters for Alan Marshall’s These are my people. With two young children, too, he had little time to paint – his portrait of Joan, hung in the Archibald Prize of 1976 (the year of Brett Whiteley’s victory) and acquired by the National Gallery of Australia in 1979, is one of few paintings in public collections from this period.

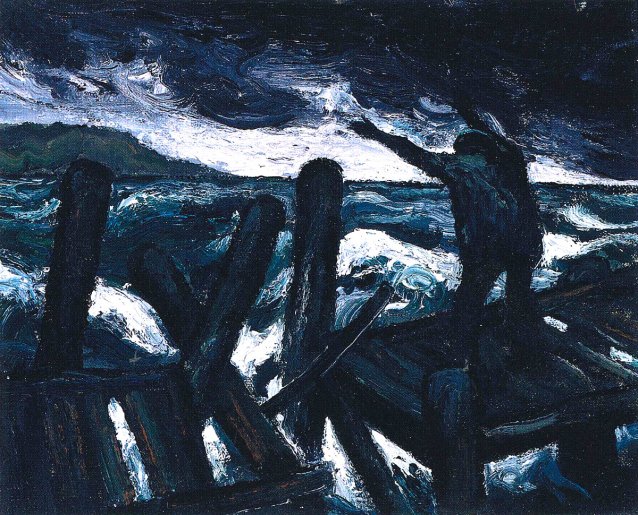

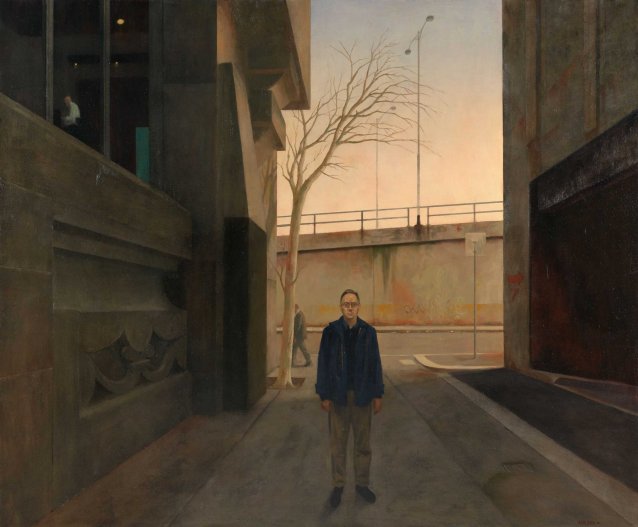

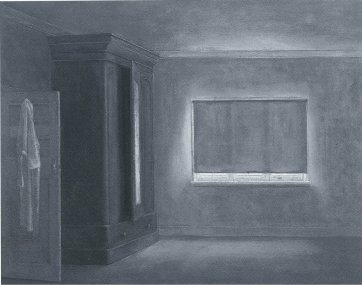

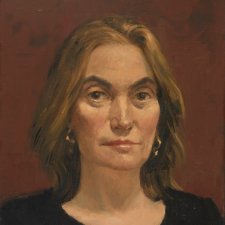

By the beginning of the 1980s, Amor was unravelling. His wife and children left Mulberry Hill in 1982. Further proof that it’s not just a romantic fancy that personal sadness can catalyse a productive turning point in an artist’s work – put it on the pile of examples worldwide, throughout history – from 1982 comes Amor’s painting Nightmare, a man, arms outflung, at night, on a collapsing jetty, waves swirling and sucking around its pillars. The sea, derelict, skeletal structures and solitary figures would henceforth recur in his paintings and prints; they’re all there in Setting moon 2002–2013, used on the back cover of the catalogue for his show at Philip Bacon Galleries, Brisbane, in November 2014. In many of his works since then, blooming from seeds of memory or dreams, the figure is effaced, occluded, glimpsed, running away. It’s a shock, in this context, to consider the many self-portraits in which he holds his own gaze – and ours – still and grave.