Featuring interviews with Matthew Abbott, Anthony Anderton, Adrian Brown, Andrew Campbell, Alex Frayne, Alina Gozin’a, Brenton McGeachie, Arianne McNaught, John McRae, Nikki Toole.

Designed for general use, the National Photographic Portrait Prize Learning Resource will also be of assistance to educators of secondary and tertiary students. Formatted for A4 printing.

What is the National Photographic Portrait Prize?

The National Photographic Portrait Prize exhibition is selected from a national field of entries that reflect the distinctive vision of Australia’s aspiring and professional portrait photographers and the unique nature of their subjects. With the generous support of Visa, the National Portrait Gallery offers a prize of $25,000 for the most outstanding photographic portrait.

Joanna Gilmour, National Photographic Portrait Prize judge and curator, introduces the Prize.

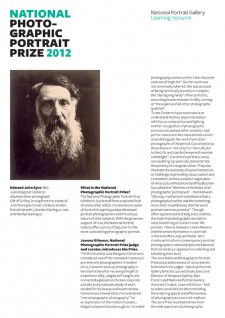

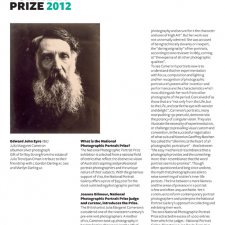

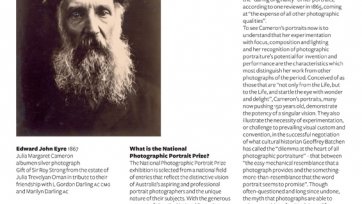

The British artist Julia Margaret Cameron is considered one of the nineteenth century’s pre-eminent photographers. A mother of six, Cameron took up photography in her late forties after receiving the gift of a camera in 1863. Largely self-taught, she converted a glassed-in chicken coop into a studio and produced a body of work notable for its beauty and inventiveness. Cameron eschewed what she considered “mere topographic photography” for an exploration of the medium’s poetic, allegorical potential and sought to “ennoble photography and secure for it the character and uses of High Art”. But her work was not universally admired. She was accused of being technically slovenly or inexpert, the “daring originality” of her portraits, according to one reviewer in 1865, coming at “the expense of all other photographic qualities”.

To see Cameron’s portraits now is to understand that her experimentation with focus, composition and lighting and her recognition of photographic portraiture’s potential for invention and performance are the characteristics which most distinguish her work from other photographs of the period. Conceived of as those that are “not only from the Life, but to the Life, and startle the eye with wonder and delight”, Cameron’s portraits, many now pushing 150 years old, demonstrate the potency of a singular vision. They also illustrate the necessity of experimentation, or challenge to prevailing visual custom and convention, in the successful negotiation of what cultural historian Geoffrey Batchen has called the “dilemma at the heart of all photographic portraiture” – that between “the easy mechanical resemblance that a photograph provides and the somethingmore- than-resemblance that the word portrait seems to promise”. Though often-questioned and long since undone, the myth that photographs are able to seize something of a sitter’s inner life persists. The line between a mere likeness and the sense of presence in a portrait is fine and often unquantifiable. Yet it continues to inform contemporary portrait photographers and underpins the National Portrait Gallery’s approach in collecting and exhibiting their work.

The 2012 National Photographic Portrait Prize attracted in excess of 1,000 entries from which the judges – National Portrait Gallery Director, Louise Doyle; Executive Director of Artspace Sydney, Blair French; and National Portrait Gallery Assistant Curator, Joanna Gilmour – had to select an exhibition demonstrating the enduring appeal and effectiveness of photography as a portrait medium. The 2012 Prize received entries from the wide spectrum of photographic portraiture as it is practised in Australia today: from baby photos to boudoir shots and encompassing everything from the profound and painful to the saccharine and sentimental; portraits taken by professional and amateur photographers; on film and (predominantly) in quick and manipulable digital formats; images of famous sitters along with those who are obscure; sitters known and loved by those who’ve captured them and others whose transactions with the photographer were anonymous, momentary or even inconsequential; and photos taken with little ceremony or thought for composition and those that were carefully, sometimes elaborately, staged.

The shortlisting of works for the exhibition was not directed by a desire to sample a cross-section of entries, nor by an intention to create a collective portrait of a community’s demographics and cultural diversity. Narrowing down a field of nearly 1500 photographs to 46 was an exacting process facilitated and determined unquestionably by the strong sense of presence in each image and by their success and effectiveness as portraits. The works selected for exhibition demonstrate the varied and innovative ways in which practitioners negotiate photographic portraiture’s capacity for capturing mood and, in particular, the manner in which it might offer insights to its subjects. The selected portraits encompass those created in close-up and in classic simplicity of circumstances – a backdrop, a sitter, a pose, a camera; and those that are the result of complex sets, symbolism and role play. Some sitters look away from the camera and others don’t. There are figures in studios and in backyards and landscapes. Others are photographed with objects or within settings that signify something of spirits and histories. These portraits exemplify too the medium’s predilection for conveying feelings and emotional states: the intensity and painfulness of grief, injustice or illness; warmth, honesty and forthrightness; wit and exuberance; stillness, introspection and contentment. In a society saturated with photographs, often consumed via the slick and pervasive language of magazines or advertising, these are indeed portraits which are distinct in being able to arrest and startle the eye. They are those which activate our deep capacity for inquisitiveness and our fascination with faces and people. They help to show us why it is that photographs can transcend the limits of likeness, gloss and documentary, and remind us instead of portraiture’s vivid possibilities.

Questions for discussion

If you were the judge for the NPPP 2012 which photograph would you select as the prize winner? What criteria would you use to make your decision?

Gilmour describes the work of Julia Margaret Cameron as “notable for its beauty and inventiveness”. Which portraits in this year’s exhibition would you describe in these terms? Why?

Can you identify any recurring themes in the 46 portraits shortlisted for the Prize? How have individual photographers chosen to approach these themes?