Nicholas Harding recently made a portrait of John Olsen, an Australian painter of great age and experience. The elder artist gave the younger only one piece of advice: ‘Be brutal’. Probably, most of us would stand with our pugnacious little Prime Minister Billy Hughes, who’s supposed to have said that when having his portrait painted he didn’t want justice, but mercy. It’s the job of portraitists to balance what they see with what their sitter wants to see. They’re tasked with producing a work that appears to have some psychological insight - preferably suggesting an intriguing aspect of character, not just an ordinary one - while gently, and plausibly, playing up the most attractive features of the sitter’s face and figure. In asking for punishment, Olsen set Harding free. From now on, the artist thinks, some of his portraits might come a little easier.

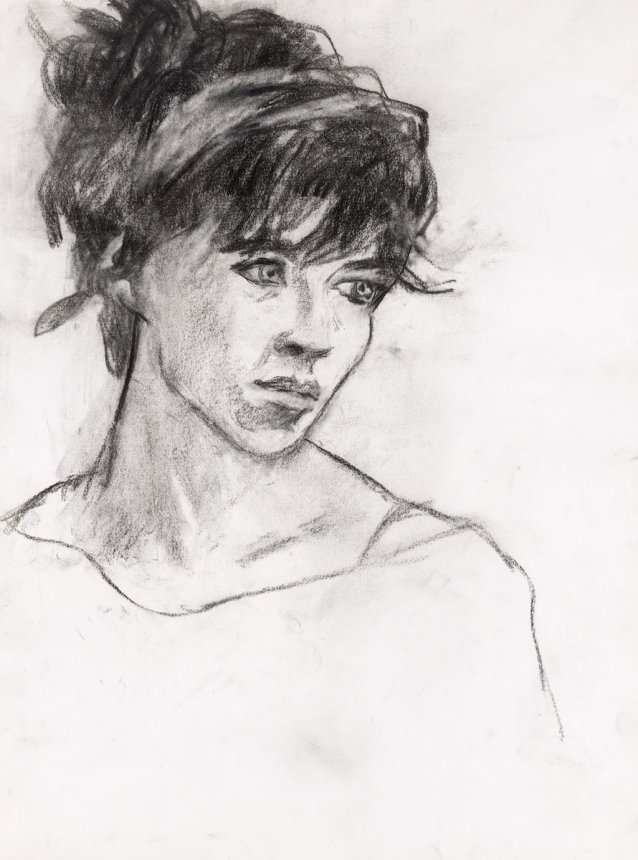

Some years ago, Nicholas Harding embarked on what turned out to be his most refractory portrait – one of the writer David Marr, who lives just down the street from the artist in Sydney’s inner west. Now, the only traces of his surprisingly prolonged effort to represent the man are a handful of drawings in a drawer in his studio. The lively example in Nicholas Harding: 28 portraits is one of them. Made in preparation for the artist’s second attempt at an oil portrait, it conveys a strong sense of the pair’s encounter. Marr faces Harding frankly, with a good-humoured, patient expression, his firm, clean lips set in a pleasant line. But somehow - independently, as it were - the oil portraits became less vigorous and more prissy the more Harding worked on them. Having scraped the first one off, he threw a second in the bin. He entered another in the Archibald Prize, kept it back from the Salon des Refusés to enter it in the Moran, and destroyed it when it was returned to his studio. The failures accumulated to a point at which Marr felt it was all his own fault. He blames his face. What’s left – a really strong charcoal drawing of Marr – stands, now, as an artefact of hope, a projection of Harding’s expectations of the work.

When Harding says he hasn’t finished with Marr yet and that one day the portrait will be achieved, his friends believe him; for they know him to be an ambitious and resolute man. He knows a lot more Samuel Beckett than Beckett’s best-known quotation, but he still likes the sound of ‘Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better.’

Nicholas Harding: 28 portraits is a small exhibition encompassing the variety in the portraits of this intelligent, industrious artist. The works differ in mediums, from the thin ink line around the quick likeness of Geoffrey Rush to the staggeringly lush paint on the monumental self-portrait; and in mood, from the meek figure of the artist’s mother-in-law Edie Watkins to the commanding one of Peter Weiss, looking like a tired old monarch about to start up with a roar. The portrait of Weiss glows in peony-pink, amaranth and crimson oils; that of John Bell is all black, white and grey. The covert, hasty sketches of unknown air travellers are distinct from the direct and careful drawings of famous men and women. In his cluttered portrait with its watery interior light, John Feitelson seems small; in his clean, hot and stark portrait, its setting the open ocean, Robert Drewe seems large. Drewe’s expression is pitiably guarded; he looks like a strong man at a loss. By contrast, William Cowan’s smartly suited, his black shoes gleam, and sitting on a modernist chair against a blank wall in the artist’s Sydney studio he emanates energy and likeability.

For some years after the boy Nicholas Harding came to Australia from England with his family, he was a shy hobbledehoy who took pleasure and refuge in drawing. They lived in Normanhurst, New South Wales, 30km northwest of Martin Place and close to untouched bush. Although they weren’t affluent, his parents were interested in classical music, theatre and art, and fatefully, they encouraged his interest too. There were Punch magazines lying around the house, and he experimented with copying the styles of its cartoons, making dozens of caricatures of his teachers and schoolmates. Early in 1973, Go Set published two of his drawings. A few years later, having given up on an arts degree, worked as a petrol station attendant and hitchhiked through Europe, he moved to the Sydney CBD.

In the mid-1970s Harding met Lynne Watkins, a girl with golden skin and hair who spent her holidays on the Clarence coast in northern New South Wales. They’ve been together ever since. Lynne’s parents Keith and Edie owned a house built by Edie’s father in Wooli in the early 1920s. In the early 1990s they retired there, moving into a new house on the same block. Harding’s spent a lot of time in his in-laws’ territory; as he’s made hundreds of views of its beaches and vegetation, the north coast’s come to feel like his natural environment. He and Lynne recently equipped a studio in Byron Bay; but they live in Newtown, Sydney, not far from his studio in Camperdown.

For a long time now, Lynne’s clothes and hair have been inner-city art-world black, her nails lacquered, her skin pale. She’s Harding’s business manager, art critic and companion, his rock and his muse, sitting next to him at the theatre, opposite him at the café. They travel together by car, train or air to wherever he’s become obsessed with the landscape or the prospect of visiting a gallery. He carries a sketchbook. Often, in the midst of drawing commuters, dogs, flowers or the features of their accommodation, he’ll throw down a quick impression of her.

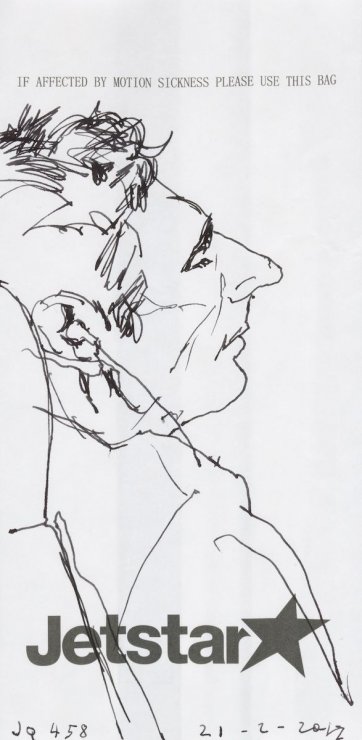

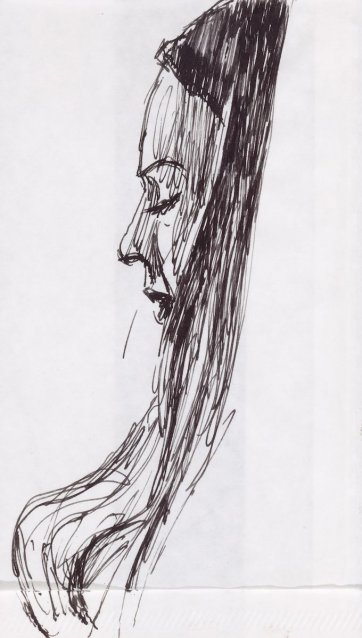

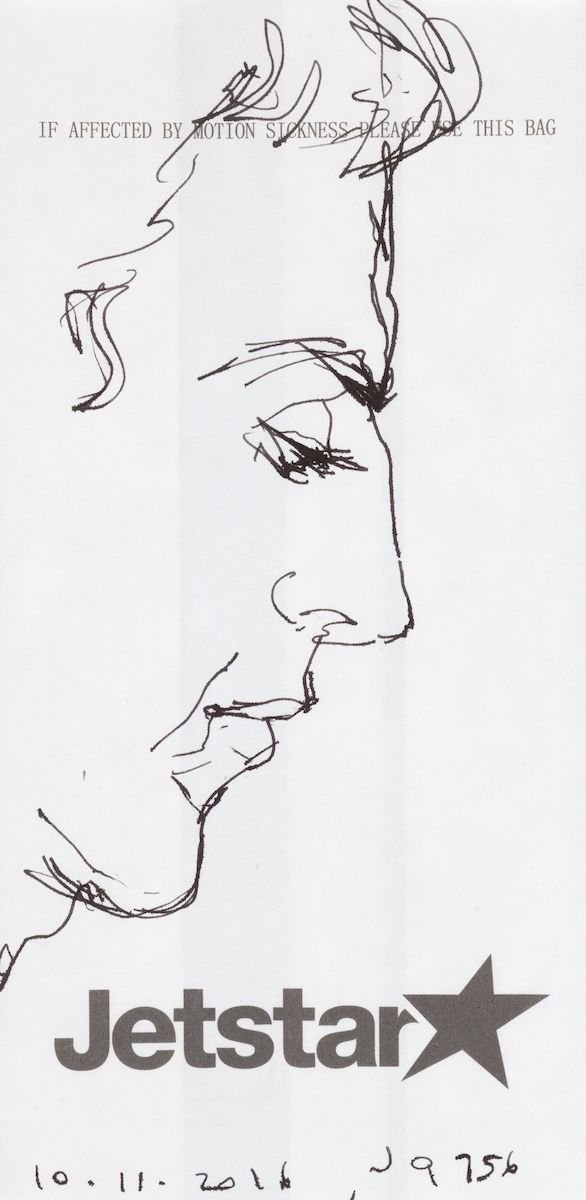

The loft of Harding’s studio comprises an archive of bound sketchbooks and loose drawings. Among its neat holdings is a substantial collection of drawings on airline refuse bags, made during the couple’s frequent domestic and international flights. If you’re a suggestible chucker, they’re a challenge to handle, but while the bags may trigger nausea, the drawings on them convey the alternate cosiness, tedium and exasperation of plane travel.

A boy dozes with his chin on his chest, a man with his arms folded. Someone props their head on hand, about to jerk awake as elbow slips from armrest.

A man with a great prow of a nose is lost in a symphony or podcast, while a young woman, her hair scraped back, pincers her phone to watch a video in flight mode. A man checks a receipt – or perhaps it’s a ragged note bearing the address of his lost, distant love.

A woman with dark locks that stream over her breast is curtained-off from the world. A flight attendant, ponytail sleek and neckline demure, plies her trolley with downcast eyes. A boy crouches forward, ruffles his hair, wonders how much longer he can stay in his seat without screaming.

The sketches were furtively executed; we imagine the passengers across the aisle from the artist, oblivious of his pen scratching and squeaking. The portrait with the closest perspective is one of Harding’s 24-year-old son, Sam, in strong, fine profile. His father’s been drawing him since he was born.

Having worked briefly for an advertising agency, in 1977 Harding started training as an animator with the Australian outpost of the American cartoon company Hanna Barbera – directed, at that time, by Neil Balnaves, who’s now well-known as a philanthropist and art collector. Harding was to work in this field for the rest of the century. By the early 1980s he was drawing for television shows including Dinky Dog and Kwicky Koala; in the mid-1980s he was on the team that made the hit movie Footrot Flats: The dog’s tale; in the early 1990s he laboured over Blinky Bill for Yoram Gross. Over this period, in his spare time, he was teaching himself to paint, attending weekly life-drawing classes and making his first forays into art competitions.

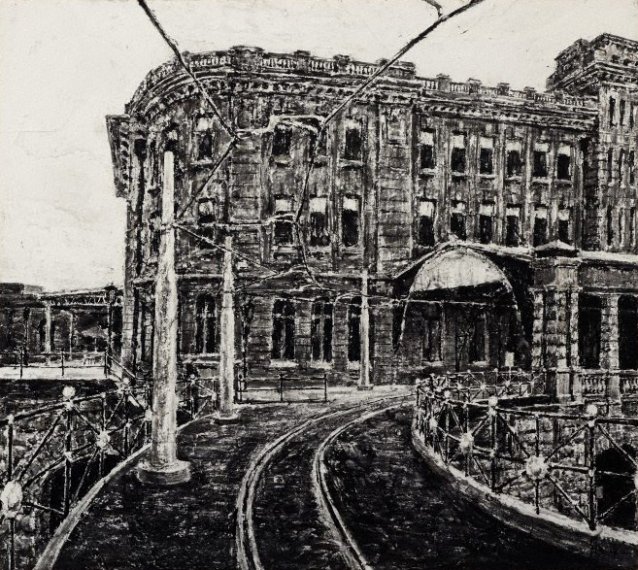

In 1992 Harding held his first solo exhibition with Rex Irwin, who’d opened his gallery in Woollahra sixteen years before. In 1993 Lynne gave birth to Sam, and Harding took out the Mosman Art Prize. He won the Kedumba Drawing Award in 1994 - the year that marked the start of his first, unbroken thirteen years as an Archibald finalist. At this time, he was refining his signature images of unprepossessing, shabby parts of the inner city, crowded with railway tracks, traffic lights, electricity poles and cables. Even at Wooli, on a thin green finger of land between the Pacific and a river, he chose to depict the concrete watertower, traffic signs and phone wires. In 1995, Margaret Olley gave one of his views of Redfern to the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Three years later, while he was still working as an animator, a portrait of Margaret Olley that he’d entered in the Archibald was officially commended. Vividly, he remembers taking a phone call from the businessman Peter Weiss, who asked him if he’d consider selling it. Flustered, Harding named a price. He’s never forgotten that instead of scoffing, or asking him to reduce it, Weiss asked him if he really thought that sum was enough. It went a long way toward increasing the artist’s confidence in himself. In the years to come, Harding would paint Olley many times; and as it happened, he would paint Weiss, too, long after he’d left the fashion industry behind.

In 2000, Rex Irwin took a risk both calculated and generous: he undertook to pay the artist a monthly allowance so he could paint full-time. Over the preceding eight years Harding had been fulfilling the duties of a represented artist - finding his own style, reliably making convincing works in that style in sufficient quantity for regular exhibitions, and creating pictures that people would actually want to buy – while working full-time at something else altogether. The stipend released him from having to earn his main income elsewhere. Harding and Irwin remained mutually loyal until Irwin retired from the gallery business in 2016; now, Harding shows with Irwin’s former business partner Tim Olsen. Over the years, the artist’s also committed to art dealers Sophie Gannon in Melbourne, and Philip Bacon in Brisbane; he aims for annual exhibitions at each gallery. Put them together with travel, commissions, entries in the Archibald and Wynne prizes and personal projects such as his theatre series, and his calendar’s crammed.

Margaret Olley was the judge of the Dobell Prize for Drawing in 2001. Her choice was Harding’s big ink drawing of Eddy Avenue at Sydney’s Central Railway Station; he was awarded $10 000 and the drawing was acquired for the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales. The same year, on his eighth outing as a finalist, he won the Archibald Prize with a painting of the actor John Bell, now AO OBE, in the role of King Lear.

Harding’s been attending theatre in Sydney since his teens. It was a decade between his attendances at the first productions of the Bell Shakespeare Company in 1991, to the moment of his Archibald victory in 2001, but portraits of John Bell swarmed in his imagination all that time. One took root in his brain while he watched Bell in The Merchant of Venice. Later, he drew him performing in Coriolanus; Bell saw the picture when a supporter purchased it for the Bell Shakespeare Company, and said he’d be happy for Harding to paint him, if he wanted to. In 1998, Harding sat in the front row of the Bell Shakespeare and Barrie Kosky production of King Lear. He came home fervid, and drew John Bell as he’d seen him leaning into a block of light, his shadow cast on the flats behind him. That year he started an ink, charcoal and conté picture of Bell’s head. In due course, encouraged by Rex Irwin, he was brave enough to approach Bell about an oil portrait for the Archibald. They had a couple of sessions while Bell was rehearsing Strindberg’s Dance of Death – though it turned out it was an expression he saw on Bell’s face while he thought himself unobserved that lodged in Harding’s imagination.

Harding’s Portrait of John Bell made the final hang in the Archibald Prize of 2000. After showing at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, the Archibald always tours to a handful of regional venues. Even once his painting was on the road, Harding found that he couldn’t get Bell out of his system. He kept thinking of the way he’d been in Kosky’s supercharged Lear; and he kept returning to work on his intense monochrome head. Living very narrowly on Irwin’s stipend, he began work on another painting of the actor, a big one, in which he wore the long crimson greatcoat he’d adopted for Kosky’s production. He was beginning to wonder how he was going to afford the paint to finish it when he took a phone call from a mortified arts administrator, who told him the existing portrait had been irredeemably damaged in transit. It was a shock, but for Harding, there was a shining upside: the insurance money was enough for him to buy the huge amount of paint he needed to complete John Bell as King Lear. The second big portrait was chosen for the 2001 Archibald exhibition without Bell’s ever having seen it; but when it was named the winner, Bell spoke vivaciously about it at the media call. Now, it’s in a private collection overseas. The ink, charcoal and conté portrait of Bell, dated 1998-2001, was donated by the artist to the National Portrait Gallery. By now, it won’t come as much of a surprise to the reader that Harding hasn’t finished with Bell. Twenty-eight years after sweltering through The Merchant of Venice in tent at the Sydney Showground, at the beginning of August 2017 he was drawing him in his pyjama costume, rehearsing The Father at the Sydney Theatre Company.

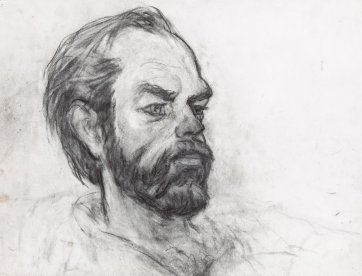

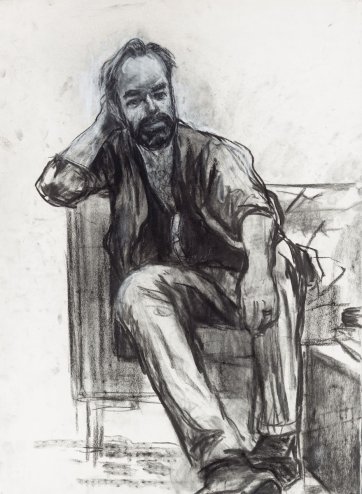

Watching stage productions, Harding’s alert to passages of high drama, grand gesture, striking effects of colour and light; but also to transitory moments of self-doubt, wistfulness, vigour and frailty. One or other of these elements and states of mind can be traced in many of his individual portraits. But among his repeated subjects, it’s Hugo Weaving, above all, who’s appeared in multifarious situations and moods. It’s odd, given the conventional hierarchy of portrait forms that has the oil painting at its apex, but Harding’s big oil painting of Weaving came before the great majority of his ink drawings and watercolours of the man; before he stated publicly that he could pretty much draw Weaving in his sleep.

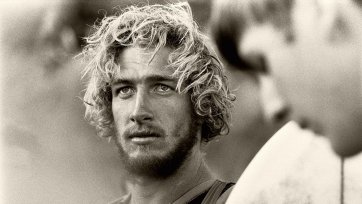

The actor and the artist met years ago, when their respective children were at school together. Harding had seen Weaving in plays and films, and Weaving liked Harding’s art. They approached each other with reserve, neither wanting to gush; their friendship developed over time. In 2011 Harding started on a portrait of Weaving, which was worked-up over several sittings at the actor’s Sydney home. During the first sitting Weaving was a trifle self-conscious, and Harding a little disconcerted by Weaving’s having shaved for a new role. The situation seemed somewhat artificial. In the second, however, the beard was back and Weaving was more at ease. As he settled into the tedium of sitting, his eyes roved. At the moment Weaving’s thoughts began to travel, Harding found the ruminative, unguarded expression he wanted for his subject. Later, in the studio, he tinkered with the composition of the picture, obliterating some elements and adding others to emphasise the famous man’s love of family and home. What remains, in the widescreen landscape format, is a sliver of a big green painting by Weaving’s wife Katrina, a hint of a red sculpture by his son Harry and a glimpse of a ukulele belonging to his daughter Holly. His glasses dangle from his left hand, while his right isn’t far from his teacup, a Japanese-style one, sitting atop a woven coaster. Of English parentage, and an enthusiast for the hand-crafted, Weaving’s a man who’s particular about his tea and the way it’s presented.

Describing the way he went about portraying Weaving, Harding refers to ‘optimising the quality of the painterly matter’ by drawing, in effect, with the paint. In fact, in parts he’s sculpted with the paint. While the arms and legs are relatively flat, the whole head is three-dimensional, its highest outcrop forming Weaving’s right brow bone and eyelid. The hair seems to have been combed into place. It’s diverting to look for all the blacks and browns in there, but it’s the face on which the artist’s had most fun with colour. It’s a plethora of pinks: salmon, dollsbody, puce, with startling streaks of violet and plum. The lips’ purple carries throughout the beard. Just beneath the hair at the back of the head is a tiny area of aqua, which streaks, too, across the ‘wall’ behind the figure.

On an Australia Council residency in Paris in 2013, Harding amassed sketches that would evolve, in Sydney, into enough oil paintings for exhibitions with both Rex Irwin and Sophie Gannon. At the same time he embarked on a series of portraits inspired by similar works by David Hockney, painted in a thick watercolour medium called gouache, extending over two sheets of thick paper, and undertaken over a two-hour sitting. As well, he made a collection of drawings of off-duty actors from a company rehearsing Romeo and Juliet near his studio on the rue Hotel de Ville. All the pictures went on to Instagram, where Weaving saw them.

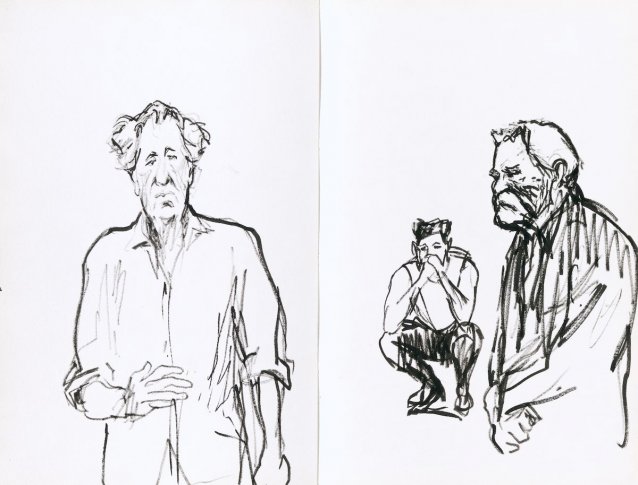

In late 2013 the actor was set to appear with Richard Roxburgh, Philip Quast and Luke Mullins in the Sydney Theatre Company’s production of Waiting for Godot. He asked Harding if he’d care to come and do some drawing at rehearsals [pdf]. Harding drew from the moment the cast took to their feet in rehearsal, persevering until he’d seen five public performances of the play and the season closed. Refined and extended in the Camperdown studio, the extensive Godot suite turned into an exhibition in itself. In a creative fever, Harding went on to draw productions of Macbeth, Cyrano de Bergerac, King Lear, Endgame and more. (The sketchbook drawing of Geoffrey Rush AC shows the actor rehearsing the title role in King Lear in late 2015.)

Meanwhile, he invited some of the STC actors to come to his studio in Camperdown to sit out-of-character for lively gouaches like those of the Paris series of 2013, painted boldly, straight onto the paper. He progressed one of Richard Roxburgh into an oil painting that has recently come into collection of the National Portrait Gallery.

At the same time, he kept working on massive ink drawings of pandanus and other vegetation that were integral to the National Portrait Gallery exhibition Arcadia: Sound of the sea. In 2015 Harding, Weaving, their partners and other friends holidayed in Sicily, where Weaving happily roamed in anonymity, picking flowers. Among the huge landscapes and luscious floral paintings that resulted from Harding’s time abroad was a view of their rented living room that Harding called Cannamara still life (Hugo’s wildflowers).

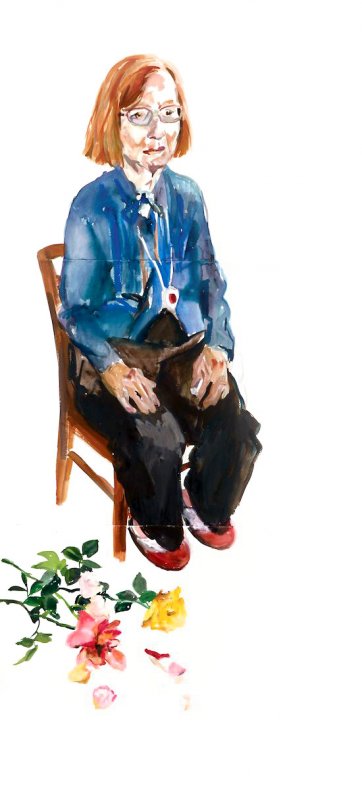

Many of Harding’s pleasant memories of his early life in England feature his grandparents’ garden, in which many flowers grew. On the other end of the world, his mother-in-law, Edie Watkins, retired from a life of teaching and created a garden in Wooli where she tended many of the thousands of flowers he’s painted over the past fifteen years: roses, orchids, kangaroo paws, banksia, frangipani, paper daisies, swamp lilies and glory lilies. Paradoxically, tiny octogenarian Edie was the catalyst for a third sheet of paper in Harding’s large watercolour portraits. He’d painted her on two sheets, but her figure terminated at the ankles, which is undesirable in a portrait. Once he added a third sheet, though, all he had to put on it were Edie’s fleece-lined scuffs. Compositionally, that was disagreeable. For balance, then, he placed some cut roses on the floor beside her and painted them. He found he liked the scale and proportions of the piece, and the way Edie’s roses spoke in a low-key way about her personality and interests. He carried elements of this picture through a subsequent series over 2015-2016.

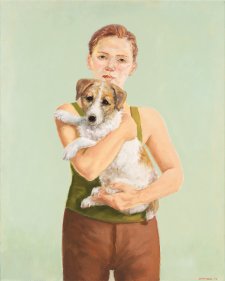

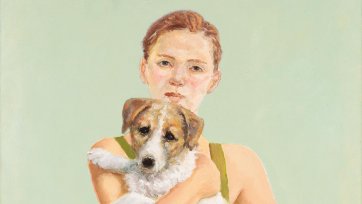

As he was drawing the Belvoir Theatre production Seventeen in 2015, Harding invited Anna Volska, actor, co-founder of the Nimrod Theatre Company and the partner of John Bell, to sit for a gouache portrait in his studio. She asked if she could bring their dog, Georgia, and he said she could, although Harding’s plastic-wrapped studio, its paint droppings copious as guano in a pelican rookery, isn’t the most suitable imaginable environment for a long-haired white dog. At first, Georgia was excited to be there, but as Anna sat motionless her interest dwindled and she took a turn around the room. Harding had achieved a pleasing head of the actor when Georgia sprang into her lap, sighed deeply, and conked out. There isn’t much to see of a small, sleeping, monotone shaggy dog; so in the second panel, Harding turned to visualising her shape in relation to Volska’s, leaving bare paper where the snowy animal obscured her owner’s shirt and trousers. If we search out the paint deployed in the depiction of Georgia, we find it mostly in her nose, ears and centre parting; yet in spite of her material insubstantiality, there’s a convincing drape and weight to her. Volska herself looks dignified and composed, her pendant earrings sounding a regal note that’s accentuated by her posture: on a chair that wasn’t really made for it, she adopts the seating posture favoured by the women of the English royal family, back straight and shins parallel, called the ‘duchess slant’. Completed in October 2015, Anna Volska with Georgia turned out to be the first of the twelve vigorous three-sheet pictures Nicholas Harding made for the exhibition The Popular Pet Show at the National Portrait Gallery in 2016.

For many Sydney artists, in particular, the lead-up to the Archibald-Wynne-Sulman prizes in the middle of each year is a fevered and apprehensive period. Harding’s been an Archibald finalist seventeen times; there have been years when his works haven’t been hung. His friends wonder if it’s really worth the heartache. But keeping his portraits in the public eye through avenues such as the Archibald and the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize has this to be said for it: it gives Harding a chance to meet people he admires. He’s put himself in a position where he can approach pretty much anyone he’s interested in painting, now, and often – though not always – they’ll agree to sit.

Harding met the brilliant young singer Megan Washington through a biennial event at the Art Gallery of New South Wales called Art of Music, founded by Harding’s friend, musicians’ advocate Jenny Morris, to raise funds for the Nordoff-Robbins Foundation, which provides music therapy for people with intellectual disabilities and other troubles. Visual artists who are invited to contribute to Art of Music create an artwork inspired by a song by an Australian or New Zealand performer. Lynne loved a Megan Washington song called ‘Underground’. Harding made a painting inspired by the song, using Lynne as a model. At the gala auction, Washington sang both ‘Underground’ and a favourite song of Harding’s, ‘Shivers’ by the Boys Next Door. He was smitten; in no time, they got to talking about a portrait; and as soon as she had a spare day she came to the studio to sit for him. The drawing in Nicholas Harding: 28 portraits is one of several charcoal portraits he made, conveying the fineness of her bones and even succeeding in suggesting, in the black medium, the extraordinary intensity of her blue eyes. Later, for The Popular Pet Show, he painted a three-panel gouache of her with her dachshund, Artie, who was flown from Brisbane to Sydney for the sitting, and she performed with striking grace at the opening of the exhibition. Harding’s intent on painting an oil portrait of Washington, but the sittings will only be possible when their schedules align.

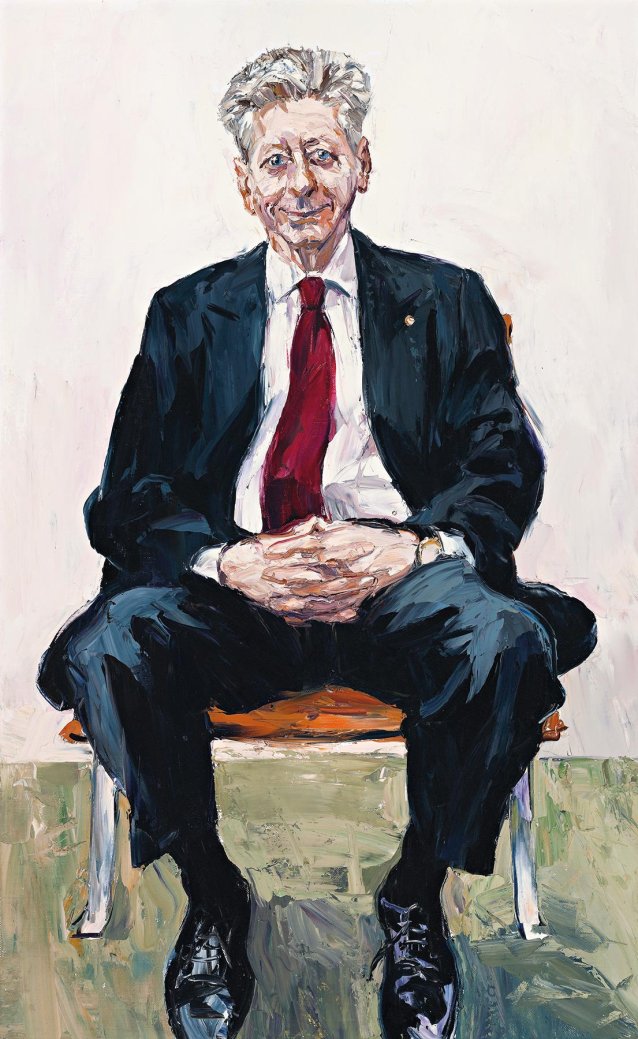

In the months before the entry deadline for the Doug Moran National Portrait Prize in 2015, Harding invited Edmund Capon AM OBE to sit for a gouache that included his signature frolicsome socks and luxury loafers in green. Capon’s the former director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, of which a generous benefactor is Peter Weiss AO. From the mid-1970s to 1997 Weiss was well-known as the head of a major Australian fashion business, but originally, he trained very seriously as a cellist, and since his departure from the rag trade (for which he never had much affection) he’s directed his energy and financial resources at facilities for music and art in Sydney. Capon contrived to bring Weiss and Harding together. Early in 2016, Harding took his paper and gouache tubes to Weiss’s house and in his customary intense flurry, made a full-length picture of him. Weiss says that when he saw his gouache sketch he was amazed at its vigour, as well as the facility with which it was achieved. He was excited about the canvas to come. With regret, however – for he’s a gentleman, and wouldn’t wish to sadden the artist – he recalls feeling, on setting eyes on the oil painting, that his figure had diminished, not just in size, but in vitality. Admittedly, his health’s been strained in recent years, but his public persona’s a large, potent one; and here he was, confronted by a quieter man.

The picture of Weiss poses the question of whether a portrait can be judged a success if its subject and his intimés have misgivings about it; because people who don’t know Weiss – and some who do - may consider his portrait, an Archibald finalist in 2016, to be one of the artist’s most imposing and humane works in this genre.

When Harding embarked upon the oil painting of Weiss, Lynne was away, visiting Edie. Having no particular reason to go home, he stayed at the studio all day and, uncharacteristically, into the early morning of the next. All that time, he laboured over the head of Weiss. By the time he left the studio he was fairly happy; when he returned the next morning, he was happier still. Because of the head, however, as he worked his way down the trunk of the figure the form of Weiss came forward in the picture plane. There was too much knee. Judging the figure to be too long, the artist decided to have the painting restretched - transferred to a new, shorter wooden frame. This was more of a chore than it sounds. The thickness and makeup of Harding’s paint militate against simply cutting a bit off the canvas and bending a once-flat section around the stretcher; such action would cause major cracking. Having prepared it carefully, and had it brought up by six inches at the framer’s, Harding liked the painting better. Once he was broadly satisfied with it, he sent photographs to Capon and to Weiss; neither thought the eyes were quite right. When Weiss came to the studio to see the painting, Harding had an opportunity to observe what was required. He’s an artist who often works from memory, agreeing with Edgar Degas that it’s all very well to copy something you’re looking at, but it’s better to draw what sticks with you, once you’re not looking at it any more. ‘It is a transformation in which imagination collaborates with memory,’ Degas said. Straight after Weiss’s visit, Harding worked on the eyes until he felt that the viewer was looking into a conscious mind; a presence; an intelligence. ‘A soul, if you like,’ he says; and indeed, most people who study portraits in galleries would like that.

The portrait of Peter Weiss part-shares a palette with Harding’s glorious oil paintings of peonies. There’s something about it that evokes a historical portrait of a European nobleman; the red wrap is the colour of the cape of Raphael’s Pope Julius II from 1511, and the colour and folds of the cloth recall the ‘turban’ in Van Eyck’s Portrait of a Man from 1433. Compositionally, it’s strong, with a sturdy cross brace formed by the rosy scarf hanging straight and the crimson one crossing the chest horizontally. In the figure of Weiss we read a degree of sadness, a little ruefulness, but also a familiarity with authority, a habit of command. With his sceptical expression in which there’s also a tinge of hope, the painted Weiss has the visage of an old king who’s tiring of fighting off contenders and dispatching conspirators. If that sounds theatrical, it’s meant to, for perhaps we can put his air of vulnerability down to Harding’s attentiveness to minimal gestures and momentary glances that round out a character on stage. Weiss may not have expected to be portrayed in a fugitive interlude of fragility. Moreover, and more prosaically, he’s disconcerted by the figure’s stopping short of his feet. Above all he feels that one side of his face is more ‘like’ him than the other. Perhaps this is why roughly half his friends and family think the portrait’s great, and half think it doesn’t quite capture him. It’s funny to think that this may have been the reaction of some friends of subjects of some of the most powerful portraits from the Renaissance onwards. Raphael may never have seen anyone apply paint to a portrait as Harding does; but the diplomacy and compromise called for in the portrait process, and the kinds of dismay and chagrin even a great portrait can trigger, have probably changed hardly at all in five hundred years.

A medium-sized landscape or flower piece by Harding costs a fair proportion of the average yearly Australian wage; but it’s almost certain to sell nonetheless. A portrait, by contrast, rarely will, either to its subject or anyone else. Most portraitists’ best hope is that exhibited works advertise their talent, so they’re remembered on an occasion that calls for a portrait. Usually, that’s when someone’s appointed to, or retires from, a position of eminence: as company CEO, say, vice chancellor, Australian of the Year, bishop, headmistress, governor-general or judge. So it was that Trinity College at the University of Melbourne commissioned the picture of William Cowan AM in Nicholas Harding: 28 portraits: Cowan’s been on Trinity’s board since 1987 and was its chair from 2005 to 2013. Harding hasn’t painted a lot of portraits on commission (that’s to say, ‘to order’). Mostly, he’s painted portraits for his own edification, and his subjects have been his friends and their friends, people from the Sydney art, theatre and music scenes. It’s odd, then, that the painting of Cowan - an engineer who became a career company director and now runs a flourishing business providing advice to senior executives - should be one of his most arresting and convincing portraits, his sitter appearing both zesty and benign.

These days, Harding usually makes preparatory studies of his sitters in gouache, but sometimes he returns to his trusty practice of drawing the face and figure from life in charcoal or ink. If he takes photographs during a portrait sitting, he draws from the photographs as a way of understanding the contours of a face. In the studio he may project the drawing onto the canvas on which he intends to paint. Before long, however, the projector will be switched off as the painting gathers its own momentum.

From the moment he made his first marks, Harding found Cowan a very congenial and cooperative sitter. Unusually, Harding says his gouache of Cowan wasn’t as lively as the oil portrait turned out to be; it was useful, nonetheless, because it enabled him to assemble the elements of the portrait according to colour. Harding regularly peppers his conversation with references to past artists’ observations: talking about how he painted Cowan, he recalled Cézanne’s saying ‘Drawing and colour are not distinct; as one paints, one draws. The more the colours harmonise, the more precise is the drawing . . . When colour is richest, form is at its plenitude.’ (Willard Wright, Modern Painting: Its tendency and meaning, first published in 1915, published by Project Gutenberg in 2012) By Harding’s standards, the portrait of Cowan isn’t a colourful picture, but he enjoyed the challenge of painting only the second suit of his entire career. The backdrop, apparently neutral, Harding tinted with the red of Cowan’s tie; similarly, there’s red in Cowan’s shirt, but we interpret the shirt as white, not pink. As an artist who paints a lot of bare feet, feet in sensible sandals and Sydney-style loafers, Harding’s particularly pleased with the job he did on Cowan’s shiny business shoes. Although shoes in a pair are the same, they can’t be painted the same, because of the way the light hits them: the highlights on the shoe on our left are light grey, those on the shoe on the right, violet. In contrast to Weiss’s feet, which moved off the canvas because of the way the figure evolved, Cowan’s feet were never intended to appear intact. When the artist projected his sketch of Cowan onto his canvas, he wasn’t happy with the composition until he moved the tips of the footwear out of the frame. The missing toe sections draw the eye out to the space beyond in a tactic that contributes to the feeling of dynamism in the portrait. We feel that Cowan’s about to jump up and pursue a positive initiative.

The portrait of Robert Drewe, by contrast, is as ill adapted to hanging in a company boardroom, school foyer or college dining hall as it could possibly be. It’s not just because the ‘sitter’ isn’t sitting, but treading water; it’s not just because he isn’t wearing a suit, though his bare shoulders are almost palpable (perhaps I’m singular in being drawn to place my hands on them, but I doubt it). It’s because of the combination of his expression, which is wounded and wary; and his position in relation to the picture plane, which is very, very close.

Robert Drewe, author of The Bodysurfers, The Rip, The Drowner and The Shark Net, was just the man to open a group exhibition called The Sea at Rex Irwin’s gallery in 2005. Soon after, Harding contacted him about the possibility of a portrait. In the summer they met to discuss it in a café in Byron Bay. They got along well, and Harding began a series of drawings of Drewe on the beach. The author found it discomfiting to be studied at his leisure. The painter was alternately pleased and depressed by his own efforts. Several attempts were scrubbed out. The holiday season ended. After a break, the two men returned to Byron Bay to renew the offensive. During a session this time, Harding looked up from his work to see that Drewe had lost focus, for a second, on the portrait process. The countenance Harding saw in that oblivious moment was what he’d been waiting for – without even knowing he was waiting. Later, looking at the portrait, Drewe was struck by Harding’s intuition. ‘In our many hours of posing and sketching, eating and drinking and chatting, I’d always presented a cheerful face, I thought, cracking jokes and bantering my way through my self-consciousness. I hadn’t let on that my life was going through a very rough patch. But I saw it in my portrait. It was all evident.’

As he did for the portrait of John Bell, and, years later, for that of Peter Weiss, for the portrait of Robert Drewe Harding seized on a ‘look’ of which his sitter was unaware; and typically, it wasn’t a moment when his subject was smiling faintly at some amusing recollection. It wasn’t until after he conceived of the face that Harding decided on the rest of the work. That came to him as he was bobbing in a gently rolling sea at Minnie Water, lazily attending to the different tempos of wavelets and ripples against his chest, squinting at the blending blues of water and sky. He went back to Sydney and painted Drewe’s body submerged. Most of us, asked to draw someone treading water, would indicate head and shoulders severed as if by a cheese-wire, producing a pictogram resembling the top third of a block of mozzarella sitting on a blue box. Harding’s skill is to convince the viewer that there’s human bulk under the water. He achieves this not by painting the body, then covering it with painted water; but by painting the water itself in smooth, curving strokes of green, white and pinkish light brown.

It’s often observed that over the past twenty years, heads in Australian portraits have been growing. Drewe’s painted head - measuring 71cm from crown to chin - may well be Nicholas Harding’s biggest. Usually, however, there’s little in the foreground of a portrait in which the head predominates (such as the portraits of Chrissie Amphlett, Mary Gaudron and Charlie Teo in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery).[1] We view such works as if we press against a window, only to be startled by a person very close to its other side. Here, the viewer feels separated from Drewe as if by about a metre of clear water. It doesn’t feel as if he’s in a tank; it feels as if we’re in the water with him, and that disconcerts, because in real life, Australians don’t swim up so close to a stranger. Further, to look into this man’s handsome face, set in mute distress, is to establish a connection that socks our middle-aged humanity in the chest. In life, to meet the eyes of a sufferer is to accept a responsibility to assist. There’s no way to respond constructively, however, to an appeal from a portrait. The sum of these factors is that looking at this picture seems like a very intimate act. It’s a cheering fact that the actual Robert Drewe’s much happier now than he was eleven years ago; but the man in Harding’s perceptive, affecting and intelligent portrait won’t ever have any confidence in his capacity to recover from the situation he was in when he was painted. We meet his eyes, and feel dismay.

For portrait amateurs and professionals alike, it’s entertaining to count the differences between the picture of Robert Drewe and that of John Feitelson. One man’s represented outside, in the glare, the other inside, in shadowy, wobbly light. Drewe’s unclothed and Feitelson wears jeans and boat shoes. Drewe has nothing and Feitelson’s surrounded by his chattels. Drewe’s head occupies fully 25% of the canvas, and looking into the extraordinary painted mess of his eyes we come close to swallowing the notion that a painted portrait can reveal something of its subject’s psyche or ‘soul’. Feitelson’s face is tiny, occluded and occupies only 0.4% of the canvas. His soul is not on view.

John Feitelson, an investor, grew up in Cape Town, South Africa, where his parents collected art. Having settled in the eastern suburbs of Sydney in 1992, he began haunting Rex Irwin’s gallery in Woollahra. Before long, he purchased big drawings by Harding of Eddy Avenue and the Dental Hospital. Feitelson and his wife, Roslyn, had some experience of the tricky business of portraiture; they’d been painted in Cape Town and didn’t much like the result, but they’d been obliged to buy the portrait anyway. In Sydney, the couple decided to try another portrait, but on different, cautious terms. Feitelson agreed to pay Irwin a non-refundable deposit for a portrait by Harding, but reserved the right not to buy the finished work if he didn’t like it.

At the time, Feitelson and his family were living in Victoria Street, Bellevue Hill, in a pocket mansion created by the architect F Glynn Gilling in the first half of the twentieth century. By the time Harding came to the house to start work on the portrait, Feitelson’s wife Roslyn, a much-loved charity fundraiser, had been diagnosed with cancer. Harding set down some drawings and went away to work on the portrait in the studio. By the time it was completed, she had died. The empty green chair is symbolic of her; but in addition, Feitelson asked the artist to add a photograph of Roslyn and their twin daughters Samantha and Lauren to the objects on the low table. When he sold the Gilling house, the portrait was put in storage. Looking at it after some years, as he pulled it out for loan to Nicholas Harding: 28 portraits, Feitelson was struck by the power with which it evoked that time and place. Diffidently, he says his own likeness is ‘close enough’ but it’s the objects around him that speak eloquently.

Isolated on a big field of canvas, Feitelson appears very much alone in his magnificent reception room. In ranks before him, his art pieces seem like a purposeful obstruction, a defensive bulwark, and the sheer accumulation of paint in the picture contributes to the inaccessibility of his small figure (that said, his painted hair protrudes endearingly from the surface). Having registered the sitter, the viewer feels impelled to decode the elements of the work. Its strangest feature is the large black structure thrusting diagonally into the top left quadrant. It looks frighteningly like a broadaxe, but it’s an art lamp, such as a light you’d see on a film set. To the left of the green chair, under a strut of the lamp, there’s a semicircular steel sculpture by Russell McQuilty in that artist’s signature red. Before Feitelson, on the table atop a Persian rug, an Atmos clock sits on the left, directly in line with his foot. The form straight in front of him is a maquette for a sculpture by Anne Ross, comprising an angular frame, figures within it and a figure surmounting it. To its right, facing the sitter, is a sculpture with the head and chest of a woman but the body of a duck; it’s by Bruce Arnott, who taught sculpture for many years at the Michaelis School of Fine Art at the University of Cape Town. Obscuring the ‘duck’s’ tail is a small copper form of an empty dress with outstretched large sleeves, a filigree bodice and a flared, ruffled skirt. On the table behind the sitter, near a doorway, is a sculpture in steel and Perspex by Campbell Robertson-Swann. In the corner stands a lamp borne aloft by the figure of a woman; brought from Cape Town, it belonged to Feitelson’s grandparents. The dark truncated cone’s just a speaker.

Feitelson particularly likes the way Harding captured the old glass in the French windows of his home, which, he remembers, had a refractive, slightly distorting character. In reality the walls of the room were plain white, and underfoot there was simple sisal carpet; but to achieve the effect of light coming through the uneven panes, Harding went all-out with colour. Looking at the work, we might be guided by Maurice Denis’s explanation of how Cézanne used colour to replace light. ‘This shadow is a colour, this light, this half-tone are colours. The white of this table-cloth is a blue, a green, a rose; they mingle in the shadows with the surrounding local tints; but the crudity in the light may be harmoniously translated by dissonant blue, green and rose. He substitutes, that is, contrasts of tint for contrasts of tone.’ By way of the greens in the window arches and the violet on the walls Harding’s created an atmosphere like that of a submarine cave with wavering, muted light seeping in through water. ‘Outside’ the central window arch is the black shape of a sculpture, again by Robertson-Swann. We look ‘through’ the right hand window at a tree trunk and a piece of white concrete balustrade, a feature right at home in one of F Glynn Gilling’s distinctively eclectic, Hollywood-Spanish-style architectural follies.

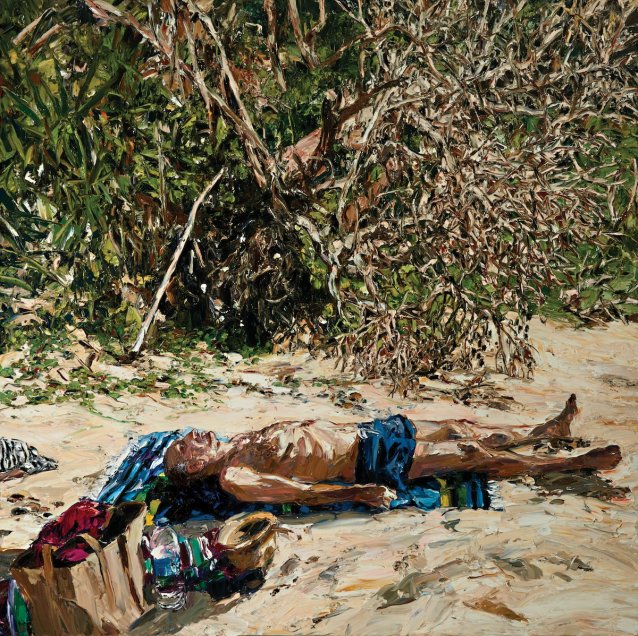

The great figure in a landscape that is Beached (Yuraygir self portrait) was the People’s Choice for the University of Queensland Art Museum’s National Self Portrait Prize for 2015 – a huge year for Harding, who’s understandably portrayed himself prostrated. The painting’s instantly recognisable as a Harding, for he’s painted scores of scenes of people on hot beaches and vegetation of the north coast. This massive work, however, synthesises elements of his body of work in a dashing, wry assertion of his accomplishment over decades. The background comprises the kind of north coast scrub that Harding’s made his own, in life and in paint. While the bush there really does look just like that – it’s hard to assimilate, visually - it’s also a metaphor for middle-aged life: it’s very difficult to get through, there are dead sections, tangled parts, bits that have dropped off, bits that are propped up, there’s a mat of weedy material on the creeping move. Often, Harding’s depicted such vegetation in ink on layers of thick paper, which he’s gouged, scored and scraped away for texture and tone. Here he’s built it up, in stunningly lavish, luscious paint; branches and sticks in the upper right quadrant are rendered in creamy chocolate and caramel oils, sand in the lower right in unctuous fudgy vanilla. Irksome paraphernalia of the adult beachgoer – all protective - clutters the foreground with rich colour. We infer the man’s come in from a long swim; he’s warming up, relishing the illicit pleasure of broiling in the sun. The string lies drying upon his bunched-up trunks. His feet splay like those of Manet’s Dead toreador flat on the sand of the bullring. His thin body with its sunken belly and prominent ribs recall Holbein’s Body of the dead Christ in the tomb. In truth, it looks as if part of his ribcage has been gnawed by scavenging animals. But still, his blue eye blazes. His motionless posing figure looks furtively at himself, painting his own portrait. It’s the perfect trope for Harding whose work is so intimately bound up with his being in the world; who’s a kind of optimistic existentialist, describing his development as a portraitist, memorably, as a process of finding out how ‘we occupy a mortal sack of blood, muscle and bone’.

[1] I am indebted to my esteemed colleague, Patrick Cox, for this insight.