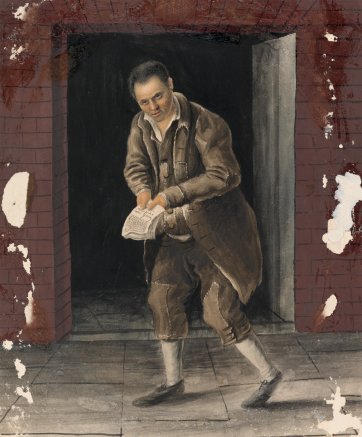

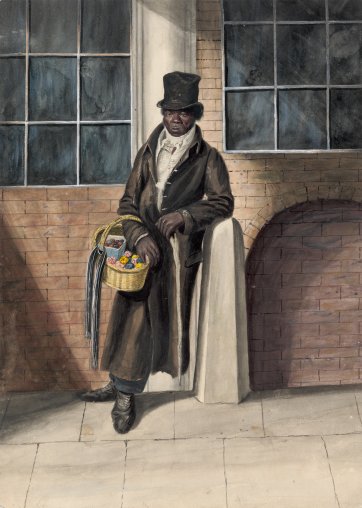

These full-length figures in watercolour, gouache and pencil date mostly from the 1820s, and almost all come from the collection of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart. (One is from the National Library of New Zealand, Wellington.)

The artist is John Dempsey (1802/03-1877), a provincial itinerant who plied his trade painting miniatures and cutting silhouettes across the length and breadth of Great Britain, although with extended periods of residence in Bristol, in England’s south-west.

At the end of the 18th century and into the early years of the 19th, imposing, formal oil portraits by artists from Sir Joshua Reynolds to Sir Thomas Lawrence dominated both the exhibitions of London’s Royal Academy and the interest of aristocratic patrons, connoisseurs, collectors and critics. However, outside this small coterie of privilege, a substantial new consumer class was emerging. Across the couple of generations prior to the widespread adoption of photography in the 1850s, a small army of artisan painters such as John Dempsey supplied this expanding market with rather more modest, domestic images of themselves.

The folio shown here was in all likelihood assembled for demonstration purposes. By depicting well-known street people, the most visible ‘remarkable characters’ of each town that he visited, Dempsey could all the more easily convince potential clients of his capacity to capture a ‘speaking likeness’.

In addition to their haunting, highly detailed naturalism, what is special about these works is that almost all are inscribed with a date and place of execution, and more than half bear the name of the sitter. This has permitted research into the lives of these people not as regional or occupational types, but as individual human beings. Between the artist’s intense, searching observation, and the biographical and socio-historical facts discovered in the archives, Dempsey’s People brings vividly to life the conditions of the working class in England during the 1820s.

Here we encounter the real-life models of the proletarian grotesques in Charles Dickens’ novels. Here we see the kind of people who came to Australia as convicts and as free settlers during the early colonial period. Here we meet the Regency poor face to face, in all their dirty, ragged, disabled, determined, energetic, persistent reality.

17 portraits

Related information

Dempsey's people

A folio of British street portraits 1824–1844

Previous exhibition, 2017Dempsey’s people: a folio of British street portraits 1824–1844 is the first exhibition to showcase the compelling watercolour images of English street people made by the itinerant English painter John Dempsey throughout the first half of the nineteenth century.

The Gallery

Visit us, learn with us, support us or work with us! Here’s a range of information about planning your visit, our history and more!

Support your Portrait Gallery

We depend on your support to keep creating our programs, exhibitions, publications and building the amazing portrait collection!